Collect Call from E.T., Will You Accept the Charges?

By Howard Scott Warshaw

It is an interesting thing to witness your past being dug up... literally! There I stood amongst tractors and backhoes, pelted repeatedly by the raging sand storm. Waiting... watching... wondering what the next scoop might reveal. Had I actually created a game so devastatingly bad, so horrifically shameful that Atari had no alternative but to truck it ninety miles into the desert and bury it?!?!

Whenever I make a game, my primary design goal is innovation. I seek to create something brand new or boldly expand the concept of some existing design. Yars' Revenge introduced many features which became industry standards. Raiders of the Lost Ark was by far the most diverse adventure on the platform at the time, and it was the first movie conversion ever. And on April 26, 2014 in Alamogordo, New Mexico, I saw E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (my third game) become ground-breaking in a whole new way - a way I had never imagined while coding it some 32 years earlier.

Howard Scott Warshaw with fellow Atari alumni Jerry Jessop and Jim Heller

This was a very interesting day. It started with a twenty-minute drive (during which we dropped 4,500 feet in elevation) before arriving at the entrance to the area containing the excavation site. Hundreds of people were already queued up there, waiting to be admitted to a garbage dump. Extraordinary. As we approached the dig proper there were c amera

crews and lights and food trucks and lots of equipment. People were scurrying around in every direction with facemasks and bandanas to keep sand and dust out of their lungs. When they opened the gates, a human wave descended upon the site.

amera

crews and lights and food trucks and lots of equipment. People were scurrying around in every direction with facemasks and bandanas to keep sand and dust out of their lungs. When they opened the gates, a human wave descended upon the site.

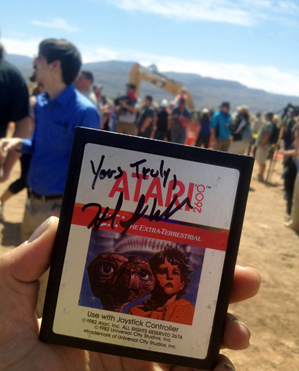

People came from all over the country, apparently for two reasons. One was to get autographs on any piece of E.T. paraphernalia they could carry (or manufacture in some cases). I signed cartridges, boxes, posters, consoles, manuals, comics, E.T. dolls, wooden E.T. cutouts, and one automobile (Ernie Cline's DeLorean)! The other reason they came was to settle the truth of a long-standing urban legend - to see if the desert would yield

a few copies (or a few million) of my infamous creation, the E.T. video game.

It was a wild day in the desert. The excitement, the energy, the sand storm, the mayor, the anticipation, the sound of heavy machinery, cameras and boom mics everywhere you turn. It was pandemonium... and it was awesome! And all of this was happening because on July 27th, 1982 I answered "Yes."

The question (posed by Ray Kassar, Atari CEO) was this: "Howard, can you deliver a game for E.T. by September 1st?" There was no hesitation. It was a crazy notion, but I knew I had to do it. And three decades later, here I stand in the middle of all this chaos, feeling incredibly honored to have created the basis of this whole adventure. I'm so grateful I said "Yes" that day.

And that was no trivial "Yes." I had accepted the shortest schedule ever contemplated for a video game... by more than 75%! By the time Atari and Steven Spielberg finished negotiations for the E.T. license, there were only five weeks left to create the game and still make the Christmas market (there's no point in doing the game if it misses that market). No one had ever done a game in less than 5 or 6 months, and I had 5 weeks! From Tuesday, July 27th to Wednesday,

September 1st. OK, technically I had 36 days, but it was already dinner time on the first day. So I started working and I kept working. I even had a development system moved into my home. The only time I was more than two minutes away from coding was driving between work and home, which I did occasionally. It was the most grueling 5 weeks of my life, but I did it.

What I did was produce the video game many consider to be the all-time worst - a game so bad it allegedly toppled the entire video game industry in the mid 80ís. Well... you canít say my work hasnít had an impact.

At one point, I caught a moment between interviews. I'm standing at the center of a hoard of fans and onlookers in this raging sand storm. Everyone is fixated on the groaning backhoe, relentlessly reaching deeper into the earth and returning with the next bucketful of antiquity... and that's when

it hit me (a realization, not the backhoe fortunately). I realized what I had actually accomplished in that five weeks. A game? Certainly. The worst of all time? Possibly. A Herculean task achieved? Absolutely.

At one point, I caught a moment between interviews. I'm standing at the center of a hoard of fans and onlookers in this raging sand storm. Everyone is fixated on the groaning backhoe, relentlessly reaching deeper into the earth and returning with the next bucketful of antiquity... and that's when

it hit me (a realization, not the backhoe fortunately). I realized what I had actually accomplished in that five weeks. A game? Certainly. The worst of all time? Possibly. A Herculean task achieved? Absolutely.

But the most significant thing I did by making E.T. in five weeks was to create a piece of video game history. Undeniably, inextricably, for better or worse till death do us part; E.T. and I were forever joined as a legend in the annals of gaming lore. I never really got it before. I certainly never considered this possibility while I was doing the game, and why would I? When I was doing E.T., there was no video game history. E.T. was just "my next game." You have to remember, video games were considered by many to be a fad in the early 80's, and the big market crash of 1983-84 pretty much proved that out.

Now, with the benefit of hindsight and three decades, we know there IS a history. Now there are "oldies" to revisit and explore. Back then, they were all "newies". We weren't making history or future nostalgia, so what were we doing? For my own part, the goal was clear. My mission was to relieve boredom, like the kind I experienced as a teen. I was a member of the last generation to grow up without video

games. Boredom was the bane of my adolescence and I understood the massive power of video games to alleviate that problem. I wanted to spare others what I had endured. I wanted to prevent history from repeating itself.

History. That's what this is all about. Reaching back to the past to answer questions, verify legends and settle disputes. As a psychotherapist I know all too well that nothing ever gets resolved in the past, only the present can provide that opportunity. And at present the dirt and the garbage and the stench kept coming up... but no games. It's a well-documented fact I have always doubted the truth of the myth. I never believed it because it couldn't possibly

make sense. Why would a financially-failing company spend a lot of time, effort, and money to dispose of something presumably worthless? Of course, when I say this I'm forgetting one of the fundamental truths of that beautiful bygone era: Whenever you expect things to make sense, you are losing touch with Atari.

I was waiting for my order at a food truck (my blood sugar was starting to crash after six hours of all this) when suddenly a roar went up from the throng. A huge crush of people were pressing closer and closer to the fence around the excavation site. One of the production people ran over to me and said, "Come on, we gotta go!" Then they literally got behind me and started pushing very convincingly. Upon wedging through the crowd and reaching the fence, I saw Zak Penn (Hollywood luminary and director of the documentary which was driving this entire extravaganza) standing there with a microphone in one hand and what actually looked like a somewhat crushed but very discernible E.T. game box. "WE FOUND IT ! ! !" he proclaimed with great triumph in his voice. There was a visible relief in his demeanor as well, since his film is much better off with a strike than a miss IMHO.

The games were there. I never thought they would be. I have never been so happy to be wrong! Whenever you expect things to make sense, you are losing touch with Atari. It was a sign, an affirmation of just how crazy Atari was. But by the same token, that craziness made Atari an incredible place to work and an amazing place to be. Atari was a hotbed of abject excess that could never last and could never be replaced. Atari (as I knew and loved it) evaporated in mid-1984 and soon thereafter I left.

But where do you go after an experience like Atari? Apparently you wind up in a sandstorm in the desert. Everyone is cheering and shouting and the air is filled with excitement and wonder (and dust)! And here come the cameras and microphones in my face, "Hey Howard, what are you feeling now?" And suddenly everything goes eerily quiet. I feel things welling up inside me. I realize the whole reason I made games

was to entertain and amuse people. To give them a break from day-to-day life and to create wonderful moments. And on this day, in the middle of the New Mexico desert, my game is doing exactly that! A piece of work I did 32 years ago is still creating a special moment for hundreds of people. My heart swells and I am overwhelmed with gratitude. And I cry tears of joy.

I was seeing remnants of an old life journey, right at the time I'm starting a new one. Atari was by far the greatest job I had ever had, until now. After Atari, my professional life was a wasteland for many years. I've done many things since Atari: real estate broker, author & speaker, robotics engineer, teacher, filmmaker, software manager and a few others as well. They all had their moments, but a psychotherapist is truly what I need to be. This is the first time

in 30 years my work is more rewarding and satisfying than what I experienced at Atari. I always believed I would get here someday, because I'm an optimist, but this was a very long time coming. How interesting this Atari news resurfaces precisely now, just as I'm hitting my stride in a bonus round of "right time, right place" in my life.

My musings continued as the heavy machinery droned on, delivering scoop after scoop of historic relics scattered amongst the useless waste. Fortunately, there were several anthropologists on hand to clarify which was which.

Life has a funny way of coming full circle. After 30 years, the gaming industry is back to making simple games for smaller screens. I've come full circle too. Back then, I catered to hungry technophiles by entertaining them. Now as The Silicon Valley Therapist I'm once again meeting their needs, but this time in a deeper, more meaningful way. I help them with their families, jobs, and relationships. My current life plan is aggressive, just like the development

of E.T. But I do hope I get better reviews this time.

Life has a funny way of coming full circle. After 30 years, the gaming industry is back to making simple games for smaller screens. I've come full circle too. Back then, I catered to hungry technophiles by entertaining them. Now as The Silicon Valley Therapist I'm once again meeting their needs, but this time in a deeper, more meaningful way. I help them with their families, jobs, and relationships. My current life plan is aggressive, just like the development

of E.T. But I do hope I get better reviews this time.

And speaking of reviews, I was asked about 'NeoComputer's' project to "fix the bugs" in E.T. The reporter seemed a tad sheepish when asking the question, but truthfully I am not uncomfortable acknowledging playability problems with my E.T. game. In other words, I am well-grounded in reality.

I have played the updated version and I believe it improves the game substantially. It eliminates the biggest problem with the game in my opinion: player disorientation. If I'd had another day or two perhaps I would have made those changes... but then again, if I had, we might not be talking about it right now.

In the end, the burial was real but it really wasn't about burying E.T. In fact, the majority of the salvaged bounty was composed of hit carts - top sellers like Defender, Centipede and Yars' Revenge. There were consoles and peripherals too. This was clearly a warehouse dump, not an E.T. graveyard. So maybe it didnít make sense to bury millions of E.T. games just to hide their corporate shame after all. But then again, what sense does it make to create

a legend around it?

As a media producer, I seek to create product which generates interest and social discourse. On that level, I feel very successful. What other Atari VCS game garners this much press today?

After all the years of speculation, this much is true: I've got one game in the New York Museum of Modern Art and another in a hole in the New Mexico desert. I faced the unearthing of my past... and I totally dug it!

Artist, technologist, creator and healer, Howard Scott Warshaw, MFT, is a therapist uniquely suited to Silicon Valley, holding master's degrees in both Counseling Psychology and Computer Engineering. His career accomplishments include distinguished software engineer/manager, award-winning filmmaker, MoMA artist, celebrated video game developer, author, and teacher. Now Howard integrates his eclectic skill set in the service of others as a psychotherapist. His private practice in Los Altos focuses on the needs of Silicon Valley's Hi-Tech community. Find Howard (and his blog) at www.hswarshaw.com. MFT#52529, and be sure to watch his documentary, "Once Upon Atari".