The Great Market Crash

By Scott Stilphen

You've heard it said before. The "Crash". It's been described as many things. If you worked in the industry or otherwise had any direct ties to it, it was the worst of times. If you were a gamer or collector, it was the best of times. Revisionists would like to convince you neither are correct and that the crash never happened. They'll claim the market simply shifted from home game consoles over to home computers, and point out that video gamers in Europe (or outside the U.S. for that matter) never saw stores offering product in bins and huge lots for pennies on the dollar. Well, I write this as someone who lived through that time and who experienced it first-hand, and I can say that, depending on your point of view, all 3 definitions are correct. It's also worth noting that this wasn't the first video game crash; an earlier one took place in 1977 as a result of a glut of dedicated systems in the marketplace. This was similar to the glut of software cartridges in the marketplace 5 years later, although that was hardly the only factor surrounding the second crash as you'll soon learn.

As far as people in the U.S. were concerned, the crash happened. Publications at the time (such as this article from the March 1984 issue of Electronic Games) referred to it as the "Big Shake-Out" (a similar instance occurred in the mid-1970s with dedicated home consoles). There were rounds of huge layoffs from all the major companies in the video game industry - Atari, Mattel, Coleco, Sega, Williams, etc. Smaller companies disappeared, seemingly overnight. It didn't matter if they produced software or hardware. As for the reasons behind why it happened or what caused it, there's no simple answer or explanation - there were many reasons for it, and with the benefit of hindsight, they all could have been avoided.. but they weren't. Our movement through history is linear, so we don't have the option to go back and do it over, but we can learn from it, and have. The video game industry today is bigger and better than ever, with sales of hardware and software reaching heights of which were scarcely dreamed.

The crash officially started in December 1982 with Atari's 4th quarter Wall Street announcement, and ended some 18 months later in the Summer of 1984, with Atari's sale to Jack Tramiel. After taking over Atari, Tramiel's first order of business was to immediately cease all video game development, lay off all but a handful of everyone involved with it, and to focus on developing and releasing a new line of home computers. The name most synonymous with video games suddenly meant something else, and by the end of the year, the U.S. forever lost their dominance in the video game industry.

So what caused the crash?

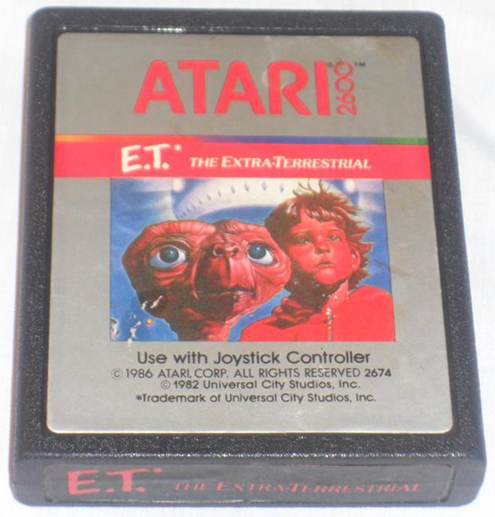

Most "weekend historians" and Wikipedia pundits will blame Atari, and the VCS game E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial specifically, but those folks are only partially right. E.T. was Atari's 2nd movie tie-in game, and the first bad one in what would be become a long line of bad movie-based games by other companies in the years following. E.T. was bad enough that it's often incorrectly referred to as the game that "Single-handedly caused the video game market to crash in the early '80s", which sounds pretty impressive, if not for the fact that it's not true. E.T., it seems, makes for a very convenient whipping post for these so-called "experts". This is the sort of typical, mindless nonsense most people and the ill-informed opinions of those scarcely familiar with the VCS's catalog will parrot. Gamers who grew up with the system can rattle off a Top 10 or 20 or 50 list of games that are all far worse than E.T. In reality, there were 3rd-party companies whose entire software library would fall into such lists, and the reason they're on those lists is the same reason why none of those games have ever been remade in the past 30 years. I'll get back to E.T. in a moment, but for now I want to go back to when Nolan Bushnell ran the company and made the fateful decision to sell it.

After 4 years of managing Atari and struggling to grow the company and expand into the home consumer market, Nolan Bushnell decided to sell the company. On July 26th, 1976, Warner Communications, Inc. (WCI) created a new division within the company, WCI Games Inc.; by October 1st, 1976, Warner formally owned all of Atari for $28 million (some accounts put the figure as high as $32 million, with Bushnell getting $15 million). Warner was founded by Steve Ross the same year as Atari, 1972. With the sale to Warner, Bushnell - now Chairman and CEO - at last had the financial resources to successfully launch a product like the VCS. One term of the sale was that Bushnell had to sign a 7-year non-compete agreement in the event he left Atari (that expired October 1st, 1983). But with Warner, Bushnell also found an enemy with Warner Executive VP Manny Gerard. Gerard had a major issue with the amount of money Atari spent on R&D, and what little marketing they did for the products they sold. As Raymond Kassar rose up through the ranks, both he and Gerard began to cut Atari's R&D while aggressively expanding Atari's marketing. Bushnell and Atari co-founder Joseph Keenan found themselves constantly fighting with Gerard and Kassar over the future of Atari, and slowly being marginalized and pushed out of the company. Before resigning from the company he helped start, Bushnell had an infamously contentious board meeting with Atari's new executives concerning the direction the company was headed, and in particular the fate of the VCS, which devolved into a shouting match with Gerard. The system wasn't selling as well as everyone had hoped, and Bushnell wanted to discontinue the system and focus on the development of the next generation console (what ultimately became the 400/800 computers). Gerard strongly felt it was too soon to dump the VCS and instead wanted to invest more in promoting it. Gerard's position at Warner gave him the upper hand in determining not only the VCS's future, but Bushnell's as well.

On December 28th, 1978, Gerard and Warner's board formally ousted Bushnell as Atari's Chairman and co-CEO, and demoted him to 'creative consultant', which Bushnell balked at. Upon his exit, Bushnell bought the rights to his Chuck E Cheese Pizza Time Theater concept and sole test location for $500,000. Joe Keenan took over as Chairman; he was previously the President and co-CEO. Ray Kassar, an ex-marketing VP from Burlington textiles, became Atari's President and CEO. The Atari board of directors now consisted of Gerard, Keenan, and Jac Holzman (senior consultant to the Office of the President of Warner).

Gerard brought in Kassar in February of 1978 as a senior marketing and management consultant, to assess the current status of Atari and report directly to Gerard, as he wanted help with establishing the VCS and give Atari a corporate structure. Kassar was an ex-marketing VP from Burlington textiles, which was about as far away from the technology business as you can get. After Keenan left in September 1979 (to join Bushnell at Pizza Time Theatre), Kassar became Atari's Chairman and CEO. In Bushnell's absence, Kassar's complete lack of experience with technology soon proved he was the wrong person to lead Atari, and his lack of compassion and understanding for what the company’s engineers actually did there began to trickle down through the company’s ever-increasing layers of management. One of Kassar's first decisions as Atari's new CEO was to cancel all the contracts Bushnell had established with all the different chip manufacturers; the idea behind the contracts was to establish a 'monopoly' for the VCS, thereby shutting out any potential rivals from releasing a competing system. Not recognizing the brilliance behind Bushnell's idea, Kassar instead saw it as a waste of money and terminated the contracts, thereby handing this bonanza of next-gen processors over to Atari's competitors. From Nolan Bushnell:

| When I sold the company to Warner and after I left, Ray Kassar looked at it and said, "Bushnell is a real idiot. Why does he have five different chip manufacturing projects going along?" He cancelled all but the best ones. One went to TI, one went to Bally, and one went to Mattel. All of a sudden, with the stroke of a pen, he generated three major competitors. |

Even though the VCS was less than a year old by the time Bushnell left Atari, it was clear this was a product that had the potential to be very successful in the near-future, especially to those programming games for it, who soon realized their efforts were largely responsible for its initial success. Some time in 1979, four of the original VCS programmers - David Crane, Bob Whitehead, Alan Miller, and Larry Kaplan (dubbed the “Fantastic Four”) – became keenly aware of their efforts (thanks to a memo circulated by Marketing), and approached Kassar with a contract proposal that would provide programmers with designer credit on the packaging and royalties for their games. Being Atari was owned by Warner, an entertainment company, they felt they should be treated accordingly, as any other creative artist (musicians, actors, comic artists, etc). Instead, Kassar dismissed them, replying,

| I've dealt with your kind before. You’re nothing than a bunch of towel designers. You're a dime a dozen. You're not unique. Anybody can do a cartridge. |

From David Crane:

| In spite of Warner’s management, Atari was still doing very well financially, and middle management made promises of profit-sharing and other bonuses. Creative people don’t like to be lied to, and there was a revolt with many people leaving and others threatening to go. Job satisfaction in the whole Engineering department was at an all-time low. At the same time, a memo was circulated from the Marketing department showing the prior year’s cartridge sales, broken down by game as a percentage of sales. The intent of the memo was to alert the game development staff to what types of games were selling well. This memo backfired however, as it demonstrated the value of the game designer individually. Video game design in those days was a one-man process with one person doing the creative design, the storyboards, the graphics, the music, the sound effects, every line of programming, and final play testing. So when I saw a memo that the games for which I was 100 percent responsible had generated over $20 million in revenues, I was one of the people wondering why I was working in complete anonymity for a $20,000 salary. When we looked closely at that memo, we saw that as a group we were responsible for 60 percent of their $100 million in cartridge sales for a single year. With concrete evidence that our contribution to the company was of great value, we went to the president of Atari to ask for a little recognition and fair compensation. Ray Kassar looked us in the eye and said, ‘You are no more important to Atari than the person on the assembly line who puts the cartridges in the box.’ After that, it was a pretty easy decision to leave. |

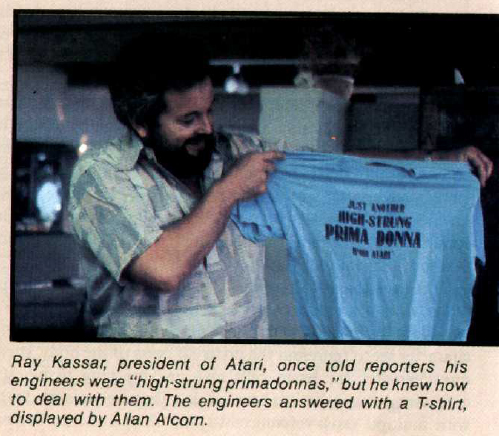

An interview Kassar did with the San Jose Mercury News in 1979 that quoted him referring to Atari's programmers as "a bunch of high-strong prima donnas" only resulted in generating more animosity towards him, and some programmers responded by referring to him as the "towel czar" and wearing T-shirts proclaiming, "JUST ANOTHER HIGH-STRUNG PRIMA DONNA from ATARI". Years later in a 2011 interview, Kassar would half-heartedly admit that his comment was "probably a mistake" but claim that it was a comment made off-the-record and that, "I really did all I could to encourage the programmers".

By September of that same year, the "Fantastic Four" left Atari and set out to prove Kassar was wrong. With the memo in hand, they sought out venture capital to start Activision, and it didn’t take long for word to get around

about just how much money Atari was making. Activision became the world’s 1st 3rd-party software company in 1979, and the following year they started releasing VCS games. Atari’s response

was to sue Activision for trademark violations and theft of trade secrets (InfoWorld 8-4-80 article). An article in the June 1982 issue of Electronic Games (pg. 9) states both parties agreed to an out-of-court settlement

involving a long-term licensing arrangement (reportedly to be a fixed royalty payment).

The lawsuit lasted nearly 2 years, during which 2 more 3rd-party companies entered the market – Games By Apollo and Imagic. During this time, Fairchild engineer Jerry Lawson had reversed-engineered Atari's VCS, wrote a programming manual for it, and started selling copies to anyone interested (he was involved with the lawsuit at one point, to show how it was possible for Activision to write software for the VCS without resorting to stealing trade

secrets). Apparently confident it would win its lawsuit with Activision, Kassar continued to treat employees with indifference (

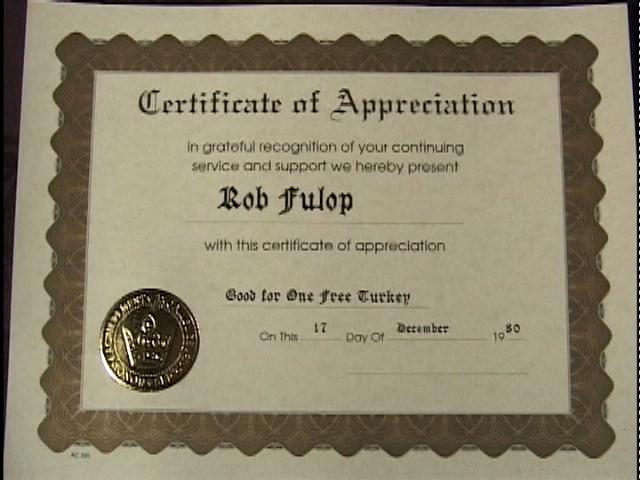

| I sat there, dumbfounded. I couldn't believe that I got a turkey for doing Missile Command. I didn't know a lot about business at the time. I was 23 years old. But I remember thinking, how stupid... I'm going to leave because of this, and all they had to do was give me $10k. If they gave me the keys to a car, I would have stayed and given them another 2 or 3 products. |

VCS Missile Command was released the following June and was an immediate hit with sales of 2-3 million carts. The next month, Fulop, along with 4 other people - 2 senior VCS programmers (Dennis Koble and Bob Smith), Mark Bradley (National Accounts Manager), and Bill Grubb (VP of Marketing and Sales) - left to found Imagic. And yet, Kassar still refused to budge on his policies. After Bushnell was ousted and Kassar personally sought to have Space Invaders licensed (although a VCS version was already being worked on by Rick Maurer), Atari's net worth skyrocketed, which no doubt reinforced his belief that his leadership was driving the company's success, when in reality he was simply in the right place at the right time.

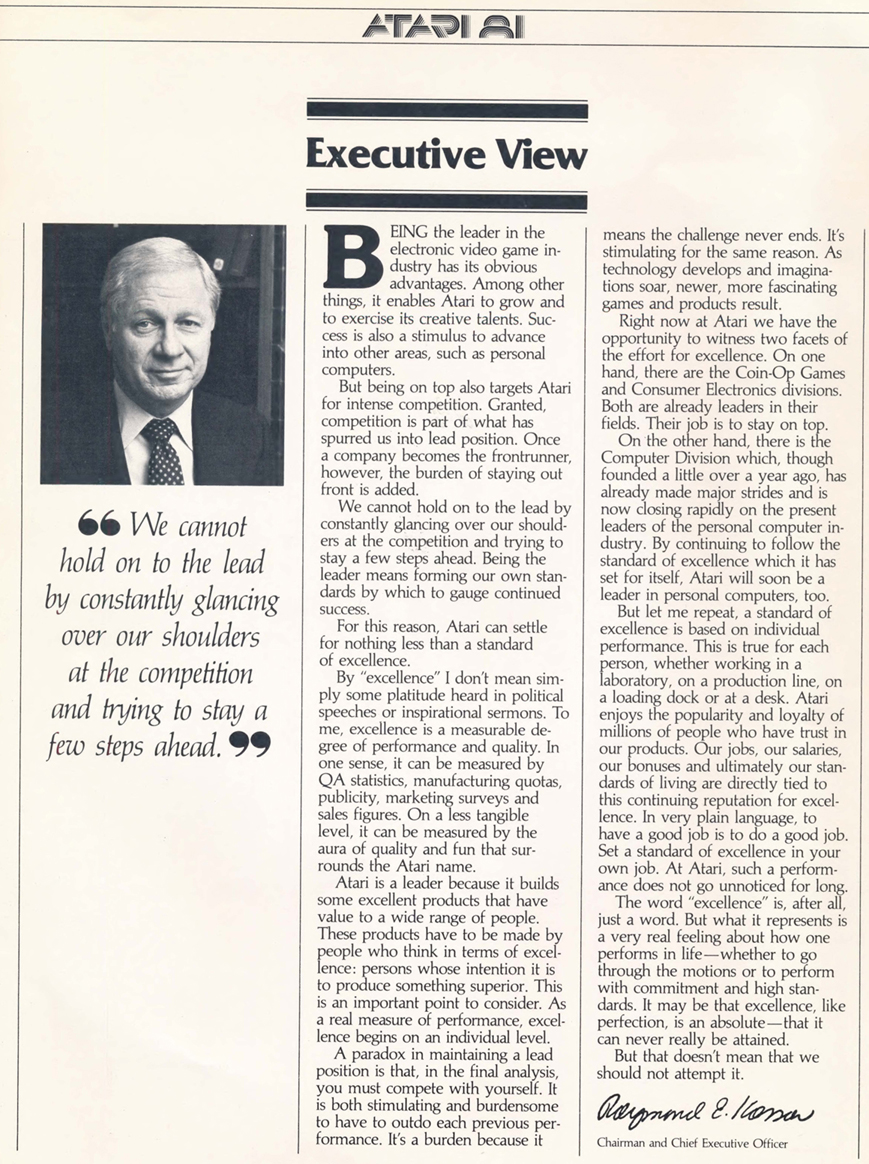

At this point, I need to point out an opinion piece that Ray Kassar wrote for Atari's internal Atari 81 newsletter (V1N4):

Ray Kassar's opinion from the V1N4 issue of Atari's

Atari 81 newsletter.

He talks about excellence and how it's just a word and how it could be an absolute that can never be attained, like perfection, "but that doesn't mean that we should not attempt it." This is the same year Kassar killed off the Cosmos, the world's first holographic handheld, which was a perfect example of how Atari wasn't merely trying stay a few steps ahead of their competition. From Roger Hector, who was one of the 3 principles behind the creation of the Cosmos:

| It went all the way through production tooling and pilot production with 8 game cartridges. We showed Cosmos at the 1981 Winter CES and Toy Fair shows, and took a year’s worth of production orders at the shows. But subsequently, Management inexplicably decided to not release Cosmos. The official reason, as told to me directly by Atari's CEO Ray Kassar, was that Atari overbooked orders for the VCS and needed more production capacity. Ray had decided to "hold off" on Cosmos "for now". |

Although Kassar re-invested heavily in the company's R&D, he had no interest in releasing anything they created; all he could see at that point was the runaway success of the VCS, and he was determined not to change course. But then again, you need to remind yourself that under Kassar rule as Atari's CEO (1979-1983), absolutely NO new hardware tech was developed and released for the home (consoles, computers, handhelds); the VCS and 400/800 hardware would be rehashed under him. He never made the attempt to innovate and do anything original. Not once. "A standard of excellence is based on individual performance" is the most laughable comment in that whole opinionated spiel of his. How many examples do we need where an individual's performance meant nothing to him? You have the groups of people who left Atari to form Activision and Imagic, with the former group establishing 3rd-party software suppliers. How about Rick Maurer's VCS Space Invaders making Atari some $100 million and only getting paid his standard $11k a year salary, who afterwards went over to Atari's Coin-Op division rather than make another VCS game? Likewise, Warren Robinett left before his VCS Adventure even got released, motivated by the same lack of credit and recognition that all designers weren't afforded. Or what about Rob Fulop getting a certificate for free turkey - not even an actual turkey - for his 2.5m-selling VCS Missile Command and leaving with Atari's top sales manager and a few others to start up Imagic? Those still weren't enough examples to get Kassar's attention. It was only with Tod Frye and Howard Scott Warshaw - 2 of Atari's few remaining experienced VCS designers) on the verge of walking away (while they were developing VCS Pac-Man and Raiders of the Lost Ark) before Kassar finally decided to start financially recognizing Atari's individual contributions by implementing a royalty program. Whether or not Kassar wrote that opinion himself is unknown, but he signed his name to it, so he approved of it. Kassar would still get a final insult to Atari's CED designers because at the same time he was setting up GCC to develop all the top arcade conversions for Atari's home systems, thereby denying the most valuable games to them to design as far as potential royalties. Not only that, Kassar personally invested in GCC, which meant he received a percentage of the sales from any GCC games that Atari released.

By the start of 1982, the Atari VCS was the ‘king of the hill’, having captured some 80% of the home video game market. The first magazine devoted to covering video games in the U.S., Electronic Games, started in late 1981; there would be a half-dozen new magazines a year later. Consumer demand was so high that people would buy just about anything, regardless of quality. The 1981 holiday season was such a huge success that many distributors ran short of product, having failed to order enough; Atari's response was to force them to preorder everything for the entire year of 1982. Distributors, not wanting to be caught short again, were forced to play Atari's game.

After the huge sales for Space Invaders, Atari was convinced that porting arcade games to the VCS was the most-profitable course of action. The year before (1979), Atari scored what proved to be the biggest licensing coup there would ever be - Namco's Pac-Man, a year before the game was released (according to Al Alcorn, Atari signed a deal with Namco in 1978 for $1 million that gave Atari the rights to all of Namco's arcade games). When both Frye and Bob Polaro were given the choice of porting either Defender or Pac-Man to the VCS, Polaro chose Defender, as he couldn't see how Pac-Man could be done, given the 4K ROM allocated for both, instead of the 8K previously used for Asteroids. In February 1982, a month before Pac-Man was released, Frye went to his manager, George Kiss, and informed him that both he and Howard Scott Warshaw were approached by 20th Century Fox to start up a new game company. At that point, Kassar finally realized that with them gone, Atari would have no senior VCS programmers left, and capitulated in giving the engineers both royalties and credit for their games. By this time, Pac-Man was by far the most-popular game in the world, and Atari's Marketing department went into overdrive promoting the fact they had the exclusive home cartridge license for it. Atari's legal department also aggressively went after anybody selling games even remotely similar to Pac-Man (such as Maganox's K.C. Munchkin for their Odyssey2 console). Atari wildly over-produced their VCS game, making 12 million carts in 1982, at a time when the installed user base was approximately 7 million. Ray Kassar is quoted in Steven Kent's book, The First Quarter, saying many top Atari execs (including himself) believed that people would buy a system just to play it. Atari was hoping for another "Space Invaders" effect of a game driving system sales to pick up the surplus, and to some extent it worked; an internal document shown in Once Upon Atari indicates Atari sold just close to 8 million carts within a year of being released, at an astounding $37-$45 each, making it the best-selling VCS cartridge ever, and Atari ended up selling some 5 million consoles.

The most-anticipated cart release of 1982 also helped Tod Frye earn a reported $1 million in sales royalties, since we can pretty much rule out "word-of-mouth" helping sales of what was soon considered to be not only a bad knock-off, but one of the worst arcade ports ever done. Only years later did the world learn Tod was given a mere 4K to program it, instead of the 8K previously used for Asteroids (although several 'homebrew' programmers have proved an acceptable version could be done in 4K), resulting in many liberties being taken; Pac-Man only looked left or right, monsters became flickering ghosts, fruit condensed into a single "multi-vitamin", dots ballooned into large "wafers", energizers became power pills, etc. The game's garish sounds and colors only added to the nightmare. By the time 8K was offered to him, the game was nearly done, which would have meant starting over. However, Atari never fully recovered from their decision to release it (and in the quantities it did) and the scathing criticism that followed. Next to technologically-superior consoles like the Intellivision and Colecovision, the VCS looked very much like the 5-year-old, 1970s-dated technology it was. From Tod Frye (Next Generation, April 1998, pg. 41 review):

| A while after Pac-Man was released, Ms.

Pac-Man was developed with an 8K ROM by a three-man team in six

months. The first Pac-Man was developed with a 4K ROM by just one man in

five months. This 4K ROM was the big problem (Ed.: In subsequent

comments, he said RAM was the big problem). My version also included a

two-player mode and this drastically ate into what little ROM there was. After the release of the game, Atari set a new rule that every game needed

to have an 8K ROM (Ed. Not true. RealSports Volleyball and

Atari Video Cube were both 4K). Why wasn't the project allocated better resources? At the time the project was started, 8K ROMs weren't available yet (Ed.: Not true. Asteroids was 8K and came out the previous summer and the bank-switching scheme was developed 2 years prior to that, for Video Chess). Also, when we started doing the port, Pac-Man wasn't a particularly big game. 'Pac-Man fever' hit between the start and the finish of the project (Ed.: Not true. Pac-Man was already very popular by the time Frye started programming his version, which would have been summer 1981. Both Coleco and Entex had their hand-held versions out later that year, and Magnavox released K.C. Munchkin for their Odyssey2 in November 1981). I have no particular technical regrets when it comes to Pac-Man. I made the best decisions based on the technology available at the time. But six months later, would I have done it differently? Sure (Ed.: I'm sure millions of people who bought the game would have done things differently as well). |

A video from the 2015 Portland Retro Gaming Expo shows Tod commenting on a new VCS version of Pac-Man and exclaiming he never understood why his version got so much criticism for the different maze layout, and for having the tunnel exits on the top and bottom, instead of on the sides like the arcade version. He also commented that he would have had a better flicker management routine had he had enough time to finish it (?). In a keynote from the same show, Tod states he wish he had made a black background with a blue maze, but claims Atari had a rule against black backgrounds because it would have burned the maze into the CRT (apparently this rule didn't apply to space games...). This makes no sense since Atari touted the anti-burn-in effects of the VCS from day one, plus Tod included the color-cycling code routine in his Pac-Man game! I've also asked several VCS programmers - including Tod's Manager at the time, Dennis Koble - and nobody else recalls there ever being a rule or even a guideline regarding the use of black backgrounds. So Tod's unfounded claim appears to be nothing more than an excuse for his poor design choices.

Frye has contradicted himself more than once, especially when it comes to specifics. But generally, he wasn't rushed with making VCS Pac-Man, and all the design choices were his and his alone. Frye is a very good technical programmer, but not one for making games that were interesting or having a lot of replay value. The fact is, VCS Pac-Man is atrocious. Most of his VCS games were either never released (Aquaventure, Save Mary) or finished (Ballblazer, Shooting Arcade, SwordQuest AirWorld, Xevious). Even his version of Asteroids for the Atari 8-bit computers is a clunky mess. The one SwordQuest game he did finish and release (FireWorld) was a disaster, along with the whole contest. He actually never understood why people flipped out over the fact the tunnels in his Pac-Man were on the top and bottom, instead of the sides, as the above video shows, and that's the essence of why his games (especially his arcade conversions) really aren't anything special. Todd wasn't a gamer, he was a programmer. To him, making games was simply product for the company to sell, or a project to be completed, like making a deck. You get some boards, you put some posts up, and you nail all the boards together. Pac-Man was a maze game with dots and tunnels and 4 enemies, so he made a maze game with dots and tunnels and 4 enemies. In his mind, it was "Mission Accomplished". Making the game look or sound even remotely close to the arcade version simply wasn't a priority of his, and yet... that was the first thing everybody noticed before they even played it. And of course once they played it, they realized it had even less in common with the arcade game. Nobody expected it to be as good as the latest homebrew versions, but there's been several hacks and homebrews in the last 15+ years to prove a better version could have absolutely been done with only 4K, so there's really no excuse for why it's so bad other than he was the wrong person for the job.

Frye was hardly the only one to blame for

the VCS Pac-Man fiasco. In the summer of 1981, Pac-Man

was the hottest game in the world. Atari had fortuitously secured the

rights to the game before it even existed, thanks to Joe Robbins.

Someone at Atari should have demanded they needed the by Christmas of 1981, and

pulled out all the stops to make it happen (using an 8K ROM, having an artist

and sound engineer, etc). Instead, the game was never assigned to anybody,

and it was left up to the programmers to decide who and when it was done?

Where were Frye's co-workers and supervisor and upper management to tell him he

needed to make a better effort? Where were the playtesters to tell Frye

his game played terribly? Where was Kassar to personally oversee what was

the company's most valuable property in its history? Everyone dropped the

ball. That game is a perfect example of how nobody was really in charge at

Atari, and no better example of how detached Kassar was from the business at

hand.

But the sales success of Pac-Man only fueled the public's desire for more arcade titles. Atari subcontracted General Computer Corp (GCC) to contribute porting arcade games, and

8K ROM chips (and soon after the SARA chip) were offered to allow for improved versions (the following year would see GCC's amazing port of Ms. Pac-Man). In late 1982, Kassar made a weak attempt to fend off the VCS's competitors with the 5200, but the console was

nothing more than a repackaged Atari 400 computer (which was originally released in 1979) with quite possibly the worst controllers ever devised, plus it wasn't compatible with either the VCS or the 400.

For most people, VCS Pac-Man convinced them the system's limitations had been reached. Whereas Bushnell wanted to effectively kill the VCS too early in its life, Kassar hung onto it too long. Still, with an installed base of some 15 million consoles, companies continued to spring up, fully intent on supplying those owners with new software. With the Atari vs Activision lawsuit settled, the path was clear for anyone to sell software for

the VCS (provided they pay Atari a royalty), and by the end of 1982, some 2 dozen companies did just that, though most of it was inferior. Atari didn't help matters with inferior ports like Defender and Pac-Man, or ill-conceived concepts such as the 4-game SwordQuest contest. The battle to win licenses for the most-popular arcade titles raised the stakes for larger companies who could afford to

play that game, like Mattel, Coleco, and Parker Brothers. Arcade companies recognized this, and would often insist on deals for 2 or more games. For example, Parker Brothers was only able to secure the rights to Nintendo's popular Popeye game if they agreed to license the unsuccessful Sky Skipper as well. After 20th Century Fox licensed its hottest property, Star Wars,

to Parker Brothers, and their failed attempt to lure away Atari's remaining senior VCS programmers, they formed their own division, Fox Video Games, and subcontracted at least 4 companies (including Sirius Software) to write games for them - some based on their movies and TV shows (Atari had been first with this approach with VCS Superman, but never fully capitalized on it). Parker Brothers struck gold with their first 2 releases: Frogger

and Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. Determined not to miss out on another property like Star Wars, Atari quickly locked up licensing deals with LucasFilm and director Steven Spielberg. They also tried a tie-in with Warner-owned DC Comics, only to realize pack-in comic books

didn't result in more sales. The bidding frenzy, as well as Atari's own

hubris, reached their absolute zenith with Atari's E.T. game.

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial was Atari's 2nd movie tie-in game, after Raiders of the Lost Ark, and the first bad one (in what would become a long line of). Most of you have heard the story of how E.T. was rushed into stores. So desperate was the head of Warner Communications at the time, Steve Ross, to cash in on what had become the highest-grossing movie of all time (or rather, to gain favor

with Spielberg in the hopes of luring him over to Warner's side), Ross paid Spielberg between 20-25 million dollars for the exclusive rights to make video games based on E.T., which was astounding. Even more astounding was Ross demanded the game be on store shelves by Thanksgiving, in time for "Black Friday" and the 1982 holiday shopping season. Kassar maintains he tried to convince the Ross it was impossible to delivery a game in so short a time frame, but that Ross insisted

Atari had to do it. However, when another executive stated when he told Kassar the same thing, Kassar replied, "E.T. is such a hot property, whatever we put out will sell." (InfoWorld December 5th, 1983, page 146 article). Unfortunately, due to the deal not being finalized until late July and pressure to get the game on store shelves in time for Christmas,

programmer Howard Scott Warshaw was left with an unbelievably short development timeframe of 5-1/2 weeks (which meant little or no game testing was done), at a time when game development took several months. Warshaw calculated he produced game code (finished, debugged, and documented) at 13 times the industry average! An article from the Chicago Tribune, dated 11-7-1982, stated

Atari planned to spend $5 million advertising the game, with Atari's VP of Coporate Advertising, Jan Soderstrom, proclaiming E.T. "Will be as big a hit if not better than Pac-Man."

Due to Ross' recklessness, Atari needed to sell some 4-5 million E.T. cartridges to turn a profit. Not learning from their mistake with Pac-Man, Atari produced that many, and only sold about 3.5 million. Some of the unsold copies (along with Pac-Man and other products) ended up being dumped in at least 2 landfills.

Although home computer and arcade versions were also planned, Atari pinned all its hopes on the VCS version, because that was the only version that had any chance of being released in time for the 1982 holiday season, and the version where the bulk of their profit would come from. That Warshaw, was able to turn out a finished, playable 8K game within the insane 5-1/2 week deadline is a feat that very likely will never be duplicated. According to Warshaw's documentary, "Once Upon Atari", Atari actually came pretty close to breaking even - over 2.5 million carts were sold in December 1982, with

another 1 million in 1983-84. It was popular enough that Consumer Guide released a strategy book about it, How to Win at E.T., the Video Game.

deadline is a feat that very likely will never be duplicated. According to Warshaw's documentary, "Once Upon Atari", Atari actually came pretty close to breaking even - over 2.5 million carts were sold in December 1982, with

another 1 million in 1983-84. It was popular enough that Consumer Guide released a strategy book about it, How to Win at E.T., the Video Game.

In late September 1983, there was another fiasco at Atari - the infamous dumping of product at a landfill in Alamogordo, New Mexico. However, in the years since the dumping, when the story is told, quite often the only game specifically mentioned being involved is E.T. It's been said that since E.T. was such a disaster (with claims of Atari being stuck with some 3.5 million copies of the game), whatever copies were either unsold or returned to Atari ended up in the dump. This is where you need to ask yourself - why would Atari dump their E.T. inventory, only to re-release the game a few years later, in 1986? The answer ties in with another unfounded E.T. rumor, that of more E.T. cartridges being made than there were active systems in homes (approximately 15 million at the time), except, there's never been any evidence to back it up, and in fact the game in question this rumor pertains to is VCS Pac-Man. As bad as the press panned E.T., they were generally as unforgiving - if not more - with Pac-Man, and rightly so. Atari made up for this ghastly mistake by releasing the fabulous Ms. Pac-Man the following year. Given sales of Pac-Man likely all but dried up after the 1982 holiday season, and with Atari's marketing muscle pushing Ms. Pac-Man as soon as people took their Christmas trees down, Pac-Man's viable shelf life had expired; Pac-Man became the pack-in console game instead of Combat, starting in 1983. Can you guess what other game ended up face-down in the desert, and most likely in greater numbers than E.T. or any other game for that matter?

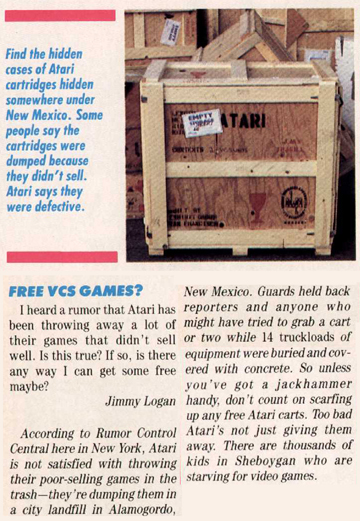

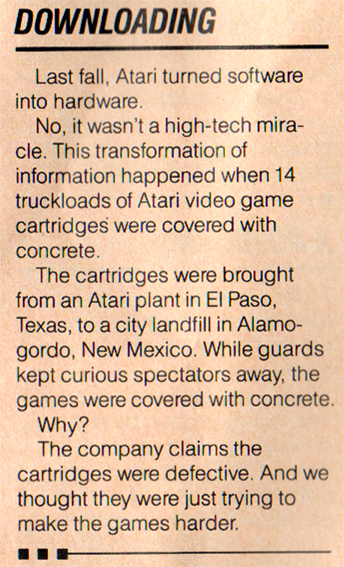

Letter from the April 1984 issue (pg. 6) of Computer Games

(left);

news blurb from the March 1984 issue (pg. 13) of

Enter

(right).

September 1983 - Atari dumping inventory at the Alamogordo, New Mexico landfill, and then covering it in concrete.

April 2014 - Excavating Atari's buried inventory at the Alamogordo, New Mexico landfill.

So why was E.T. blamed for the crash? It's true that most reviewers back then gave E.T.

poor marks, but Bill Kunkel's review

in the most popular magazine at the time, Electronic Games,

went out of his way to criticize the game... that is, when he finally bothered

to review it (despite a promise in their January 1983 issue that readers would

hear about the game there first, nothing was mentioned about it until their

April issue, at least 4 months after the game was released). The review

is perhaps one of the shortest reviews ever,

at a scant 12 sentences) and this was for Atari's 2nd-most aggressively-marketed

games (after Pac-Man). The page layout all but buries the review; it's sandwiched between two large Mouse Trap photos, and with no accompanying photos for E.T., it's very easy to flip past without noticing it. The reviewer describes the game as looking like it was programmed in 5 weeks (hmm, now how would someone outside of Atari know that?)

and that it consists entirely of falling in holes, avoiding government agents, and "following directional arrows in dicated at the top of the screen". The review has all the signs of an Atari insider pumping

Kunkel with information about the short development time (probably the same person who wrote the infamous

Easter egg letter

in the January 1984 issue), and Kunkel simply based his opinion around that.

He also clearly didn't play the game or even read the manual (for starters, you don't follow the arrows), and

didn't even mention what the player's objective is! The reviews in

EG's 1983 and 1984 Software Encyclopedias gave the game a final rating of 4 (out of 10) due to the "poor" graphics and audio - two areas in which the game excels! Due to how fast E.T. was programmed, Atari

announced both E.T. and Raiders of the Lost Ark in the same issue

of Atari Age, with Raiders actually shipping a week after E.T.

Being both were based on movies by the same director, and both games were made by the same programmer, this was 'evidence' enough to suggest that one game was basically a modified version of the other. An article in the May 1984 issue of EG (pg. 68) suggested as much, saying both games used "the same object code. In this case, a choice of graphics evidently

made no difference, since neither title did well." This was a statement EG co-founder Bill Kunkel made years later on Digital Press' forum ("As for Raiders, it simply reprocessed the code from another piece of crap -- the infamous E.T. -- albeit to slightly better effect." -

link), so it's clear Kunkel was the reviewer for E.T., and he made it abundantly clear he had a personal vendetta against any of Howard Scott Warshaw's games. Well, all of Warshaw's titles each sold over a million copies, so I'm not sure what Kunkel's yardstick for doing well was. Readers certainly deserved a more balanced review than the biased mess

EG sometimes put forth.

dicated at the top of the screen". The review has all the signs of an Atari insider pumping

Kunkel with information about the short development time (probably the same person who wrote the infamous

Easter egg letter

in the January 1984 issue), and Kunkel simply based his opinion around that.

He also clearly didn't play the game or even read the manual (for starters, you don't follow the arrows), and

didn't even mention what the player's objective is! The reviews in

EG's 1983 and 1984 Software Encyclopedias gave the game a final rating of 4 (out of 10) due to the "poor" graphics and audio - two areas in which the game excels! Due to how fast E.T. was programmed, Atari

announced both E.T. and Raiders of the Lost Ark in the same issue

of Atari Age, with Raiders actually shipping a week after E.T.

Being both were based on movies by the same director, and both games were made by the same programmer, this was 'evidence' enough to suggest that one game was basically a modified version of the other. An article in the May 1984 issue of EG (pg. 68) suggested as much, saying both games used "the same object code. In this case, a choice of graphics evidently

made no difference, since neither title did well." This was a statement EG co-founder Bill Kunkel made years later on Digital Press' forum ("As for Raiders, it simply reprocessed the code from another piece of crap -- the infamous E.T. -- albeit to slightly better effect." -

link), so it's clear Kunkel was the reviewer for E.T., and he made it abundantly clear he had a personal vendetta against any of Howard Scott Warshaw's games. Well, all of Warshaw's titles each sold over a million copies, so I'm not sure what Kunkel's yardstick for doing well was. Readers certainly deserved a more balanced review than the biased mess

EG sometimes put forth.

Unfortunately, Raiders took the brunt of E.T.'s criticisms, which was also the start of the "all movie-based games are bad" stereotype. Unlike the case with E.T., there weren't any widespread claims of people returning Raiders, and if they did, it wasn't because it was a flawed game but rather that it was too hard. In fact, Atari was so swamped with requests from gamers on how to solve it that they offered (for free) both a hint sheet and a step-by-step solution. In the final analysis, E.T. - even with all the negative attention it received - still ended up being the 8th best-selling VCS game Atari ever made. Atari planned to have the game on store shelves by Thanksgiving, in time for "Black Friday", so at most it was available for sale 2-3 weeks before Atari laid their Wall Street 'egg' of less-than-expected 4th-quarter profits - something that really started the countdown to Atari's demise. So how could a game released mere days before such an announcement be responsible for the fallout from said announcement? It can't, but in the short attention span-driven world of the media and their audiences, the truth of the matter hardly matters.

On December

8th, 1982, Atari dropped their own belated "Pearl Harbor" attack on Wall Street and announced their 4th Quarter sales estimates were only a 10-15% increase, instead of the 50% they originally predicted. It's important to note that they weren't losing money at that point, they just weren't going to make as much

as they forecasted! Atari,

seeing their 4Q troubles ahead and their market share dropping to 60%, tried to

restructure their distribution network a month before. They had some

130-140 distributors for their products - far too many than was needed - and

some started getting into price wars with each other. On November 1st,

Atari told all

their

distributors their contracts were cancelled and that only a small number of them

would be awarded exclusive contracts. Since Atari never bothered to have

exclusive distributor contracts prior to then, their competition simply used the

same distributors. Those who were forced to preorder for 1982 and were

later dropped by Atari simply started shipping unsold product back to them.

Since Atari didn't audit the distributors they had dropped, they were forced to

buy back whatever they were sent.

their

distributors their contracts were cancelled and that only a small number of them

would be awarded exclusive contracts. Since Atari never bothered to have

exclusive distributor contracts prior to then, their competition simply used the

same distributors. Those who were forced to preorder for 1982 and were

later dropped by Atari simply started shipping unsold product back to them.

Since Atari didn't audit the distributors they had dropped, they were forced to

buy back whatever they were sent.

Warner's stock took a big hit after Atari's Wall Street announcement; overall the stock market dropped 29 points in the 2 days after, as did all video game-related stocks. This one incident, coupled with Mattel's announcement the next day that it was actually taking a 4th-Quarter loss, caused a domino effect throughout the entire video game industry. The day after that,

Perry Odak, Atari's President of CED, was forced to step down, basically taking the fall for the Wall Street announcement (NY Times article), with two other senior execs, Lee Henderson and Thomas McDonough soon following him. An article in the April/May 1983 issue of Vidiot talks about Atari's announcement and the fallout from it (and how Steven Ross profited from it to the tune of 1.5 million dollars).According to the editorial in the March 1983 issue of Video Games (pg. 6), analysts had been predicting a "shakeout" in the video game business for about a year before Atari's announcement, and all the negative reports that followed in the months after only fueled the fears of a market crash. Still, the news shocked most analysts and started Atari's precipitous fall, as well as the industry's. Imagic's public stock offering, which was scheduled a week later, was put on hold in the hopes they could make another attempt in early 1983. Smaller 3rd-party companies that had sprouted up all throughout 1982 suddenly found the ground underneath them give way. They didn't have the luxury of hoping to wait out the 'big shake-out', for even though 1983 saw sales increase approximately 25% overall, all companies saw their sales plummet due to the increased competition. The coin-op industry was even more susceptible to the increased competition. Arcade earnings were but a fraction of home sales, but were still far below what they had been. Like home games, operators saw the same drop in 1982-83. Laserdisc games were the last-ditch efforts to sustain their earnings growth, and when that failed, most arcades closed, and operators sent many an arcade game to the dumpster.

Nearly all of the 1982 start-up companies closed down within a year, and yet by the end of 1983, nearly 3 dozen more companies had sprung up. Seeing Activision's apparent success, they were convinced the market would soon level off and become stable (much like how some Titanic passengers felt the ship would level off and stay afloat). At this point, there was literally a glut of product - more than there was shelf space available for them - and most of it was awful. But, instead of throwing out their product (Atari had the right idea, but for the wrong reasons), they used it to help write off their debts. The vulture circling overhead waiting to pick their bones was the firm Kandy Man Sales, who bought up their inventory and resold them to distributors. One company's games, U.S. Games, ended up with Carrere Video / TELDEC. Carrere Video Distribution (in conjunction with Tiger Electronics) purchased several U.S. Games titles and re-released them in PAL format. Most (such as the games of CommaVid, Data Age, Spectravision, Telesys, Wizard Games, and Xonox to name a few) found their way into the supply chain, which ended in a huge pile of product on tables or in bins in stores such as Kay-Bee and K-mart. This only made a bad situation worse, for stronger companies such as Activision and Atari couldn't compete with a market full of games costing an average $5 each. People may be dumb, but they're not going to spend $25-$35 for Atari's new game - no matter how many great reviews it gets - when they can buy several for the same amount, especially after being burned by the marketing hype for Pac-Man and E.T. Atari's market share fell to 40%. As these new companies quickly collapsed, they sold their inventories to distributors for practically next-to-nothing. Meanwhile, Kassar continued to invest heavily in R&D with no long-term plan on what to do with anything that was created. By the end of 1983, Warner was looking at half a BILLION in losses, and the industry had passed the point of no return. As for all those R&D projects that Atari and others were working on, they soon became known as 'vaporware' (a term coined by a MicroSoft engineer the year before). This article from the December 1983 issue of Electronic Fun lists but a few.

LEFT: News blurb in the September 1983 issue of Electronic Fun (pg. 99); RIGHT: Article in the October 1983 issue of

Video Games (page 39)

If all those 3rd-party companies hadn't dumped their inventory on the market, Atari (and stable companies like Mattel or Imagic) could have recovered from mistakes like Pac-Man and E.T. Instead, much like E.T.'s ending, the whole industry went into hibernation until someone (Nintendo) came along to revive it. Sure, they could have weathered the storm better than most, but as it happened, they all made their costly share of mistakes. By the time the thread that Steve Ross pulled from Atari's cloth over E.T. had completely unraveled, Ross was forced to sell off Atari to ensure Warner's future. Ever since becoming Warner's acquisition in 1976, Atari had become the plane on which Warner's fortunes were soaring, but when Atari started its infamous nose-dive, it left Warner susceptible to a hostile takeover, and they felt they had no choice but to unload Atari as fast as they could.

IEEE spectrum mentioned the situation in an article in their January 1984 issue, sub-titled "Chaos in Home-Computer and Video-Game Markets" (pg. 81):

| There was considerably less optimism last year as sales slowed in the home-computer and video-game industries. Startup video-game companies proliferated in 1982, and while industry sales for video games grew by approximately 25 percent in 1983, the number of video-game cartridges produced increased by many times that amount, flooding the market. Also, consumers began moving away from the purchase of traditional video games and towards home computers. As a result, Atari Inc. of Sunnyvale, Calif., a subsidiary of Warner Communications, dumped truckloads of game cartridges in New Mexico after absorbing heavy losses (Atari said the cartridges were defective). Several recently started companies - like U.S. Games, a subsidiary of Quaker Oats; Data Age; Fox Video Games; and Games by Apollo - closed their doors. Imagic Corp. of Los Gatos, Calif., sold its inventory and cut staff: games that previously cost $30 now reached the consumer priced near $5. Even Activision Inc. of Mountain View, Calif., which held on to profit margins longer than most other companies, posted a large loss late in the year. |

From Howard Scott Warshaw:

| Atari, for years, was using the leverage that they had to just screw distributors everywhere. When they had a hot game, they would force distributors to buy copies of the old games that weren't selling anymore, just to get copies of the new game. This is the kind of stuff they were doing. So when things started to turn on them, everyone in the industry was waiting to jump on them with both feet. That's what killed Atari - the ill will that they had generated through their cutthroat business practices on their way up. |

Both CEO Raymond Kassar and Executive VP Dennis Groth were charged by the Securities and Exchange Commission with insider trading from selling personal shares of company stock minutes before the infamous December 8th, 1982 Wall Street announcement (New York Times article). Atari's stock that day dropped from $52 a share to $36, a 30% drop; Kassar sold his shares 40 minutes before the announcement. In early 1983, two stockholders, Meryl and Richard Gloven, filed suit against Warner Brothers, charging Chairman Steven Ross sold some 140,000 shares of his stock prior to Atari's Wall Street announcement (April/May 1983 issue of Vidiot, page 8), so the man who pushed for E.T. to be rushed to market turns out to have been guilty to insider trading to an even larger degree. Imagine that. But Ross was only starting turn Atari upside-down...

As a result of being caught by the SEC, Kassar was finally forced to resign 7 months later, in July 1983, and was replaced by James J. Morgan. Warner CEO Steven Ross actually interviewed Morgan, who worked for cigarette company Philip Morris USA and helped develop the Marlboro Man advertising campaign; yes, another ex-marketer from another static business field. Morgan took 2 months off before starting as the new Chairman and CEO of Atari, in September; John Farrand from the coin-op department was the interim CEO. Morgan's first decision was to implement a 30-day freeze on all development. He also fumbled with deciding where to have the 800XL manufactured - a delay that eventually cost Atari to miss what would have been a very profitable Christmas season for them that year, at a time when there was a big push in the industry towards home computers. The few 800XLs that reached store shelves were quickly sold, with a large percentage of those being returned due to being defective. In the summer of 1984, Atari was some $400 million in debt, and on July 1st, Warner Communications basically blindsided Morgan and broke up the company, retaining the arcade and AtariTel divisions and selling off the C.E.D. (Consumer Electronics) and H.C.D. (Home Computer) divisions to Jack Tramiel, the founder of Commodore, and a group of unknown investors for $240 million. Warner received no cash, but received $240 million in long-term 'promissory' notes and warrants for a 32% interest in Tramiel's new venture. Tramiel, in return, received warrants giving him the right to purchase one million shares of Warner common stock at $22 a share. In other words, Ross gave Atari away. This was basically an accounting maneuver by Ross to improve Warner's stock to stop a hostile takeover by Rupert Murdoch. Ross had previously rejected Philips offer to purchase 100% of the company because he wanted to keep a stake in Atari.

In conclusion, there were many factors which lead to the market crash of 1983-84:

Warner's management style clashed with Nolan Bushnell's, and led to him leaving the company. He was replaced by Ray Kassar, who had no experience with the video game industry, and was either unable or unwilling to adapt to it. His outdated management policies left Atari with no long-term plans on how to proceed beyond the products they had, and his short-sightedness/lack of vision let to competitor's consoles using next-gen processors that Atari paid to develop.

Atari relied on the VCS for too long and was too late in replacing it with next-gen hardware. Upon Bushnell's exit from Atari, he implored on Gerard and Kassar to stop cutting back on R&D. With the VCS's slow sales in its first year, Bushnell felt it was essential for the company's future to invest in developing their next console, especially with the increasing advancements with the technology. Gerard and Kassar looked at the VCS as the next record player, only needing to increase marketing and advertising while releasing more games for it. The 400/800 hardware was initially designed to be the next console after the VCS, in 1979, but Kassar instead repurposed it for a new line of home computers (400/800). By the time competitors Mattel and Coleco started gaining market share with their Intellivision and Colecovision systems, the same 400/800 hardware was quickly redesigned and released as a console (5200), but this was late 1982 and far too late to make much difference.

Atari's engineers were the 'lifeblood' of the company. Instead, Kassar refused to compensate Atari's engineers for their efforts, or credit them on the games they created, viewing them as insignificant and easily replaceable, and the result was Atari ended up creating their own competition with the rise of 3rd-party software companies (whereas before they enjoyed complete control of the VCS), which led to a glut of product. By the time Atari instituted a royalty program and started crediting designers, it was too late.

Atari failed to implement using larger ROM chips in cartridge production years before, and instead focused on constantly trying to maximize their profit to satisfy their "bottom line" (i.e. greed). 8K bank-switched ROMs were developed for Video Chess back in 1979, but were only used once (for Asteroids) prior to Pac-Man. 8K versions of games like Pac-Man and Defender would have been more faithful and generated more sales, but Atari only decided to implement wide use of 8K ROMs after realizing that after the fact with Pac-Man.

Atari's fabled R&D created dozens of amazing products, most of which would have helped Atari maintain their technological edge over their competitors and helped them branch out into other fields. Instead, millions of dollars and countless hours were wasted on projects that were either shelved or later sold off and released by other companies.

Atari's Marketing department ended up dictating not only what games should be done, but in what timeframe. The lesson of trying to force game development to fit some preconceived 'deadline' should have been learned with E.T., but in the 18 months that followed E.T.'s release, Marketing's scheduling demands only created more pressure on the programmers to meet them.

The E.T. debacle, which should be placed squarely on Warner CEO Steve Ross, who paid Steve Spielberg anywhere between 20-25 million for the rights to the game, all in a vain attempt to win him over from Universal to Warner. In the end, all Warner got from wooing Spielberg was the Gremlins franchise, which was hardly worth losing Atari for, along with Pelé and the Cosmos NASL team as well article.

The mess with how Atari handled their distributors was yet another problem that could have been avoided. Atari had $2 billion in sales for 1981 with 80% of the video game market in both software and hardware, but were unable to completely fill orders for their distributors for the previous 2 years. So in October 1981, they forced distributors to preorder for all of 1982 and mistakenly gave them the option to return any unsold product for credit. Atari failed to change their policy with the rising wave of 3rd-party software suppliers that hit the market in 1982, and by the end of the year, distributors exercised their option to return unsold product, which Atari was unprepared to handle, and ultimately dumped most of it in a landfill. If 3rd-party companies hadn't dumped their inventories onto an already-oversaturated market, Atari and larger companies like Mattel and Coleco might have recovered from their own mistakes. Instead, much like E.T.'s ending, the whole industry went into hibernation until Nintendo came along to revive it.

The replacement for the 400/800 computers, the 1200XL, was a complete failure. It was announced in December 1982 (a week after Atari's infamous Wall Street announcement) and was quickly seen as nothing more than a cost-reduced 800 in a new case, but with enough incompatibility issues with older software (even with some of Atari's own software) to force Atari to discontinue it 6 months later. At the same time, Atari announced the follow-up 600XL/800XL models which failed to reach the market until late 1983, missing the lucrative Christmas shopping season. Kassar couldn't have picked a worse time to fumble Atari's position in the home computer market, as 1983 was the same year Commodore's Jack Tramiel instigated a home computer price war that was intended to primarily hurt Texas Instruments (to return the favor for a price war that TI started with Commodore with the calculator business years earlier) but ultimately dragged everyone down. The 800 was priced at just over $1k in spring 1981, but 2 years later was well under $200 - less than the cost of manufacturing it.

Lastly, the U.S. was in the midst of a recession, from July 1981 to November 1982 (LINK), so for Atari to force distributors to preorder for all of 1982 - and to order older, outdated games as a requirement when ordering the latest games - when consumers were cutting back on how much they spent was woefully ignorant on their part. Pushing out subpar products like VCS Pac-Man and E.T., the 5200, and the 1200XL on top of it did nothing but hasten the inevitable.

As a footnote, Manny Gerard was interviewed for the Antic podcast on September 8th, 2015 and he admitted Atari made some mistakes, but claimed the biggest one was allowing 3rd-party software companies to make games for the VCS. Naturally, he failed to acknowledge the fact that the formation of 3rd-party software company Activision was solely due to Kassar's poor treatment of Atari's programmers. As Rob Fulop opined, it would have taken very little (financially) to keep people from leaving. In 2025, Gerard was again interviewed for The Legend of SwordQuest podcast shortly before his death, and in part 5 ("Decent Into Darkness"), Gerard mentions asking Kassar why he didn't license Donkey Kong, which was the most popular game at the time, instead allowing Coleco to successfully launch their Colecovision system with. Kassar's response was that Coleco wanted $2 royalty per cartridge and he wasn't going to pay that much! With Warner behind them, money wasn't Atari's problem; Kassar's mismanagement was. That's why I have management listed above as the first issue, because that alone directly or indirectly led to all the other issues mentioned. Gerard convinced Warner founder Steve Ross to purchase Atari, and then later brought in Kassar to lead it, who ultimately destroyed it. Letting someone experienced in running a non-dynamic company like Kassar run a very dynamic company was the biggest mistake in my opinion. Atari was first described to Gerard as a "fast growing technology-based entertainment company". Whatever possessed him to pick an ex-marketing VP from Burlington textiles to run Atari, we'll never know (he passed away in December 2023 at 90 LINK. Kassar passed away 6 years earlier LINK), but it's been surmised he wanted someone to bring some stability - both financially and structurally - to what was at the time a very 'fly by the seat of your pants' company with very little marketing behind it beyond word-of-mouth. The result was a company that changed from one that was never afraid to take chances on new ideas and innovations to one that became increasingly stagnant in the marketplace and extremely top-heavy in its corporate structure and marketing strategy. Combined with a CEO that failed to respect his employees and recognize those whose contributions truly drove the company's success, by the time Kassar's 5-year reign ended, most of Atari's creative minds had left to work elsewhere or to start up their own businesses.

The infamous market "crash" of 1983-84 decimated the video game marketplace. It impacted every company, including Atari, and by early 1984 only a few companies remained in business.

Part 2 about the "crash" can be found HERE.