QR Code and the VCS

By Scott Stilphen and Greg

Bendokus

(2021)

The emergence of Audacity Games has taken homebrewing to the next level. Their first release, Circus Convoy, employs 2 different 21x21 QR (Quick Response) codes - a static one that generates a URL to log onto their website to register the game, and a dynamic one for high score submissions. Every cartridge has a unique serial number, so the QR code is specific to every cartridge as well.

Registration QR screen in Circus Convoy.

However, Audacity Games wasn't the first to use QR code with a VCS, or in a VCS game. The first VCS game to incorporate QR code was Other Ocean Interactive's The Stacks in 2012. The game was based on Ernest Cline's Ready Player One book and designed in conjunction with a contest. The QR code was proof you had completed the game and qualified you for the next part of the contest.

Ending of The Stacks showing the QR screen.

In 2018, Seth Robinson created what he calls the PaperCart. This is literally what it means. He converted several 2K and 4K VCS programs to QR code and printed them on cards. By coupling a Raspberry Pi and a Picamera with what appears to be a custom 3D-printed holder, he simply inserts a game 'card' and it's automatically scanned in and run using the Atari VCS emulator with Retropie. If the card is then removed, the game stops running!

Seth Robinson's PaperCart Picamera Data Matrix card reader

setup.

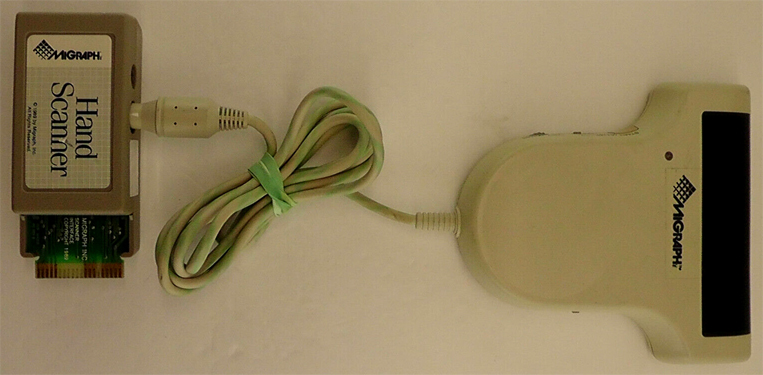

Long before QR code, there was something called Cauzin Softstrip (now known as Datastrip code). Cauzin Softstrip was the first commercial 2D barcode format and was introduced in 1985. It could store up to 1K per square inch and was designed to allow magazines to distribute computer programs by simply printing a pattern on a page. The appeal of this format was the ability to scan in a program instead of typing it in or purchasing a floppy disk copy. Unlike QR codes, which can be 'read' with today's smartphones, a handheld reader or scanner was required to read Softstrips. Migraph, Inc. was one company that offered the Hand Scanner for use with Atari ST computers:

Migraph's Hand Scanner for the Atari ST.

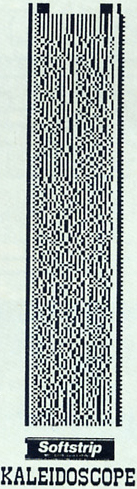

There were a few problems with this format that quickly led to its demise. The scanners used very early capture software which didn't allow for a capture preview, so you had no idea whether you made a good scan of anything until after the fact. Since the scanner was operated by hand, you needed a surgeon's hand to keep it steady long enough to scan something as small as a postage stamp, let alone a barcode listing. It was entirely on the user to somehow scan something at the correct speed; there was nothing to guide you in any way. Since the scanner itself was small, if you wanted to scan an entire page, you had to make several passes and then use the software to join the scanned 'strips' together. You would be presented with 3 very crude file preview images side-by-side, and guaranteed, 1 or more of the images would be skewed in some way. The other issue was with the quality of the image you were trying to scan. With a Softstrip, if the ink was smeared or the print quality was poor, it would be impossible to make an accurate scan of it. On top of that, the readers cost anywhere from $100 on up. Without a large enough user base for the technology, and with no alternatives or solutions for the inherent problems (illustrated by this October 15th, 1985 New York Times article), Softstrip was quickly dropped from the few magazines that offered it.

Example of Softstrip code listing.