Al Alcorn interview

By Brian Deuel

(2000)

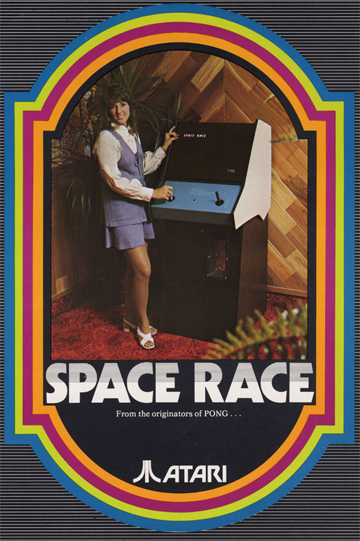

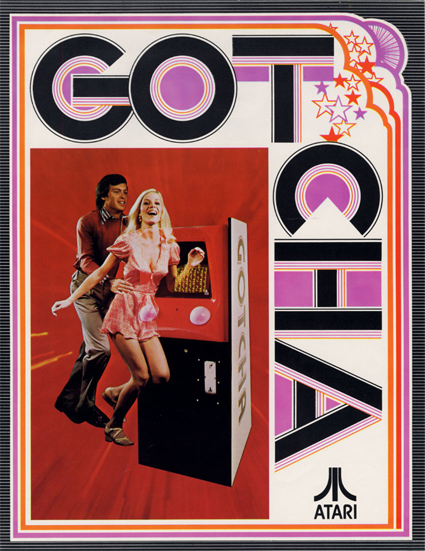

Al Alcorn is one of the pioneers of coin op arcade games, having designed and engineered Pong with Nolan Bushnell, and also working on Atari's second and third games; Space Race and Gotcha, respectively. He also engineered Pong for the home market. I am very excited to present my interview of this legend to you!

Q: What is your educational background? What kind of career goal did you have in mind before Nolan Bushnell contacted to come work for Syzygy (later known as Atari)?

Al Alcorn: I grew up in San Francisco and always wanted to be an electrical engineer. I started fixing TVs when I was 13 years old. While I was an electrical engineering student at Cal in the late '60's, I alternated working six months at Ampex and going to school six months at Cal. That was where I met Nolan, Ted Dabney, Steve Mayer, Larry Emmons, Steve Bristow, and others. I wanted to specialize in analog engineering; I found it more interesting than digital logic. At Ampex, I wound up making video circuits using the new TTL logic chips.

Q: Syzygy engineered Computer Space for Nutting Associates, and then worked on Pong. At which point did you join Nolan and Syzygy? Were there any game designs that were worked out, then rejected, before Pong was engineered?

Al Alcorn: Around 1971 I was back at Cal and heard that Nolan had quit Ampex and

gone to work for Nutting Associates and was making a new secret machine. We thought this was foolish since Ampex was a great place to work, and working for some unknown company was very risky. In 1972 I was back at Ampex, but Nolan and Ted Dabney were off doing Computer Space. In May of '72 I went to lunch with Nolan and Ted in Nolan's company car, a 1972 Buick Station Wagon. They offered me a job as an engineer for $1,000 per month and 10% of the stock in Syzygy.

At that time Ampex was beginning to stumble, so I took the risk and joined up. Nolan and Ted were consultants to Nutting, and they both quit to start their own company with me. Nolan formed Syzygy at the beginning so as to use Nutting to pay to develop, manufacture and distribute Computer Space. He used the revenue stream from the royalties from Computer Space, a Bally development contract, and our route operation to fund Syzygy to develop our own game that became Pong.

Al Alcorn: Around 1971 I was back at Cal and heard that Nolan had quit Ampex and

gone to work for Nutting Associates and was making a new secret machine. We thought this was foolish since Ampex was a great place to work, and working for some unknown company was very risky. In 1972 I was back at Ampex, but Nolan and Ted Dabney were off doing Computer Space. In May of '72 I went to lunch with Nolan and Ted in Nolan's company car, a 1972 Buick Station Wagon. They offered me a job as an engineer for $1,000 per month and 10% of the stock in Syzygy.

At that time Ampex was beginning to stumble, so I took the risk and joined up. Nolan and Ted were consultants to Nutting, and they both quit to start their own company with me. Nolan formed Syzygy at the beginning so as to use Nutting to pay to develop, manufacture and distribute Computer Space. He used the revenue stream from the royalties from Computer Space, a Bally development contract, and our route operation to fund Syzygy to develop our own game that became Pong.

When I showed up in June of '72, Nolan was busy designing two-player Computer Space for Nutting, and Nolan set me to work designing a simple ping pong video game. Nolan told me that we had a contract from General Electric to design a home video game on a ping pong theme. I had the prototype running in three months, and I was very disappointed because it had about 75 TTL IC's and would cost way too much for a high-volume home machine. It turns out that Nolan had something else

in mind. He lied about the contract with GE and gave me this project because it was the simplest game he could think of and he just wanted me to practice on something. The real successful machine would be something more complex than Computer Space, but he would give it to me after I had practiced on Pong. Since I was under the impression that this was to be a real product, I worked hard to make it playable and inexpensive. Once we got the prototype working, it played so

well that Nolan decided to put it in a cabinet and put it on location and see what it did. Ted Dabney built a cabinet for it over the weekend, and Nolan and I placed it on location at Andy Capps, and the rest was history. I still have that machine.

Q: What was the design process for Pong? How were Pong (and other early arcade games) "programmed" using the available TTL state machine technology of that time? Any technical problems during the process?

Al Alcorn: Video games didn't have processors in them until '74, I think. The first games were complex, digital machines that generate a video waveform to run a monitor. Circuits were added that created spots of light that could move around the screen and other simple shapes [to] interact with. One of the hardest things about the early days was that you could not get a monitor. At that time, real monitors cost about $300 for black-and-white. I wound up going to the local Pay-Less and buying a $75 black-and-white television and using my TV experience to convert it into a monitor.

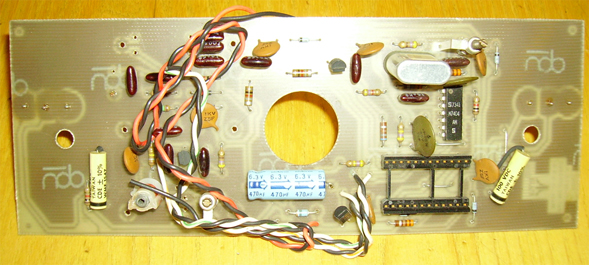

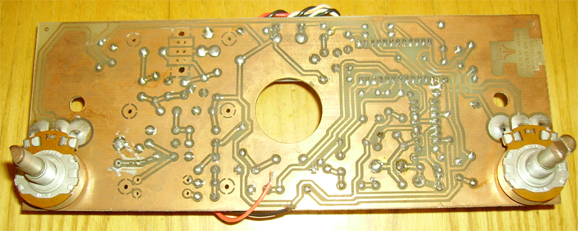

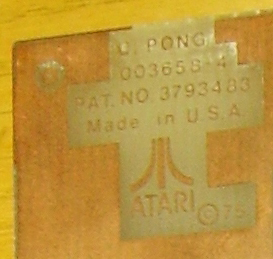

Original Pong prototype.

Q: Who actually designed the game, you or Nolan? Did the Odyssey 100 (first home console) design have any influence?

Al Alcorn: It depends on how you define "designed". Nolan described what he wanted in terms of a ping pong game with a net, paddles, score, ball and sound. We discussed his design for Computer Space and he showed me the schematics. I couldn't understand his schematics, but I got the idea. Computer

Space had three printed circuit boards [and] I wanted Pong to have one. Nolan had no involvement with the circuit design of Pong.

I never saw an actual Odyssey machine, but I think I saw pictures of it and heard it described. Nolan may have gotten the idea from them but you will have to ask him. As I said before, Nolan didn't take Pong seriously since it was just practice, anyway. I wasn't very impressed with Odyssey; it was built with analog components and the play was terrible. The design for Pong turned out much better than Nolan expected, and it seems that the digital technology was well suited

[for] that game.

Q: What was the first indication that Pong would be a great success? What did it cost to produce a game like Pong in those days?

Al Alcorn: When we first put it on location, I asked Nolan what would constitute good performance. I think he said that if it did $25 a week, that would be a good game. It was doing over $100 per week right away. After about a month on location, I got a call that the machine had broken. I went down

to Andy Capps and discovered that the machine stopped because the coin box was so full that it jammed the mechanism.

It probably cost us about $500 to manufacture the first Pongs. We sold them for about $1,200 apiece and the operators paid cash up front.

Pong's very first quarter. Photo courtesy of Al Alcorn.

Q: What other arcade games did you do while at Atari? What is/was your design philosophy?

Al Alcorn: I did Space Race and Gotcha. After that, I became VP of R&D and I had to manage a team of engineers to design lots of games. I also stepped in and fixed the first driving game called Gran Trak. We had built about 100, and they were badly engineered that they had to take

them back. I came off of sabbatical and re-designed it.

I liked to keep my designs simple and cheap.

(LEFT) Space Race flyer; (RIGHT) Gotcha flyer

Q: What was the atmosphere like at Atari in the early days? How did it feel to be a part of the new industry of video games?

Al Alcorn: We were not part of a new industry, we created the industry! (Ed.: Well, that's what I meant!) Many companies came along and copied what we did, but we were always a couple of years ahead of them. It was a very exciting place to work. At first our goal was to be as big as Bally in coin-op. Then we decided that we needed to get into consumer games and we sold "Consumer" Pong to Sears. They were exciting times. We risked the company every year on new ideas. We were young and if it failed, we could always get jobs in Silicon Valley.

Q: How long did you stay at Atari, and what other products did you work on while you were there?

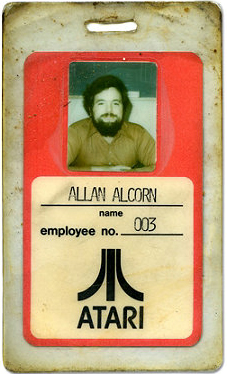

Al Alcorn: joined Atari in June of 1972 and I was employee number 3. I left in 1981 and went "on the beach" for a couple of years. I personally designed Pong, Space Race, Gotcha, and home Pong. I started the Consumer Division. [A small team and I] created Cosmos.

Q: Why did you leave? What did you go on to do after Atari? Anything else game-related?

Al Alcorn: I left Atari because it ceased to be fun for me under the Presidency of Mr. Kassar (Ed.: Ray Kassar was brought in as president of Atari shortly after Warner Communications bought the company from Bushnell).

After Atari, Nolan, Joe Keenan, and I started Cumma, a home video game electronic distribution company. It was a kiosk that allowed a consumer to install new game software in special video game cartridges using RAM. It failed with the video game market in '83. In 1986 I joined Apple Computer as a Apple Fellow; I left in '91. In 1994 I started Silicon Gaming to make next-generation slot machines for Las Vegas. It was somewhat like what I think an arcade game should

be. It was meant for the Vegas casino market and was bulletproof.

Q: What are your thoughts about the industry these days? What are your feelings about having played a major part in creating the industry?

Al Alcorn: I am happy to see how video games have become part of our culture. I never expected that to happen. I am very lucky to have played a part creating something that has touched so many lives in a positive way.

I feel that video games have devolved into a few categories. I would like to see new types of games instead of new versions of the same game.

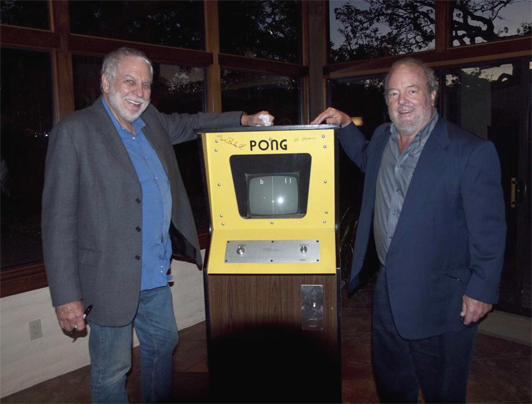

Nolan Bushnell and Al Alcorn signing a Pong arcade machine.

The following photos were taken by Scott Stilphen at Al Alcorn's home in 2007:

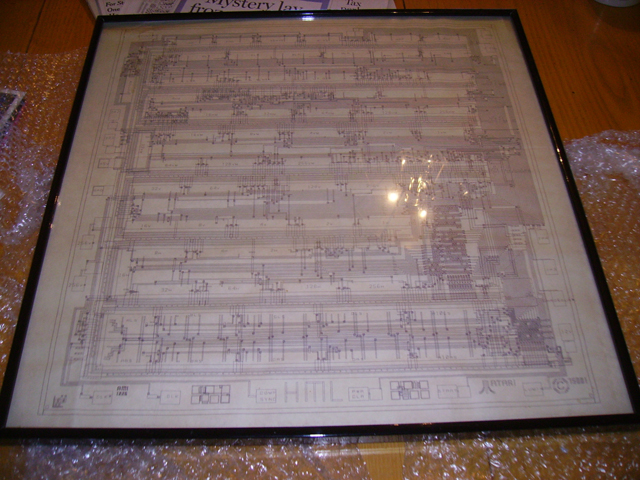

Original Home Pong chip layout.

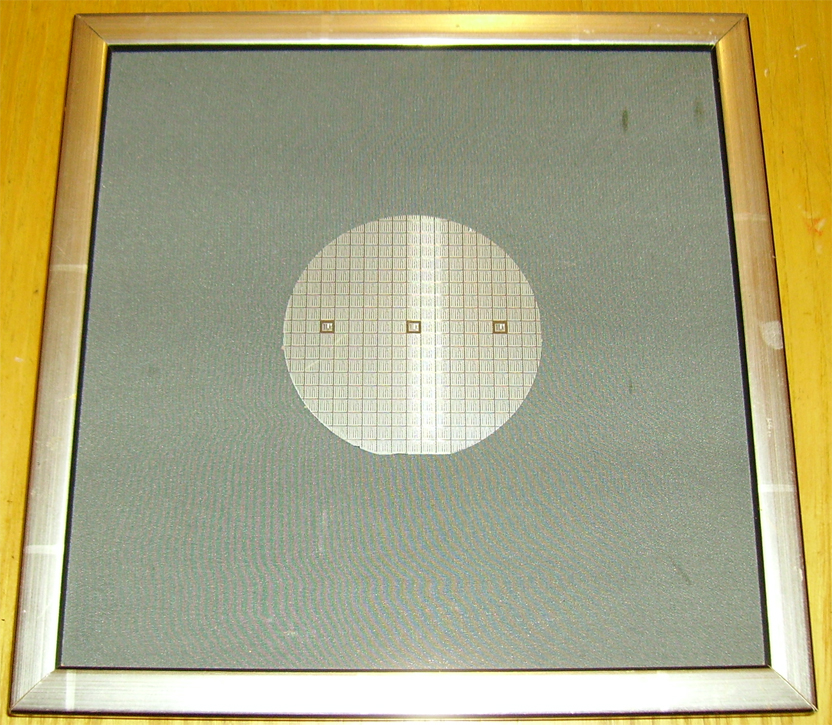

Original Home Pong chip photomasks.

Home Pong chip.

Silicon wafer for Home Pong.

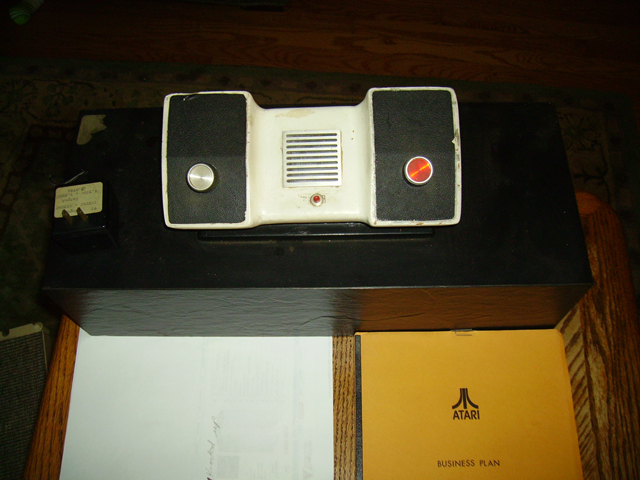

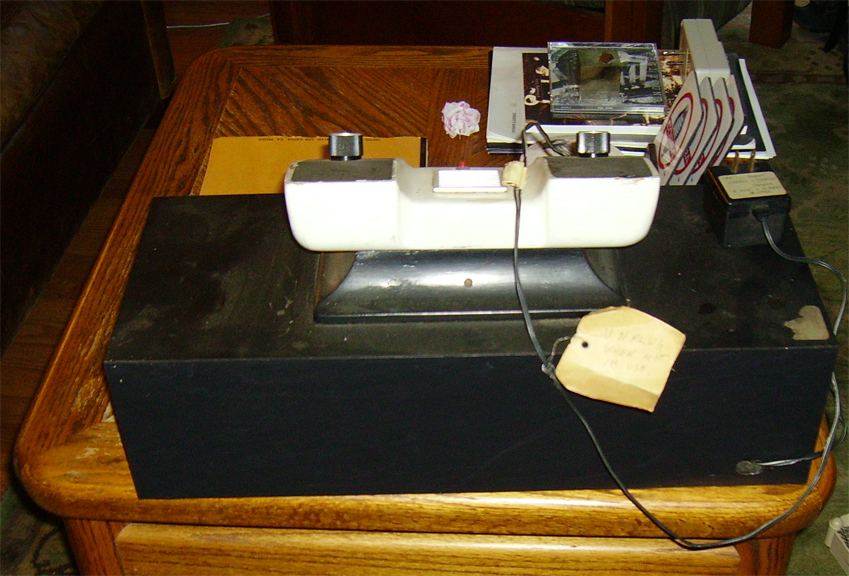

Home Pong prototype system, version 2.

Home Pong prototype pcb.