Lee Actor interview

By Scott Stilphen

(2007)

Having been in the video game industry for close to 20 years, it can be said that Lee Actor has nose for what works and what doesn't, and especially an ear when it comes to audio! His early work with sound development programs for the Atari 800 paved the way for those used today, such as Pro Tools. Along the way, he worked on VCS/2600 Lasercade at Videa, and several arcade games when Videa became Sente. He's since traded in his keyboard for a baton, having become an accomplished composer and conductor, but he was happy to stop by and talk about his former career as a game designer.

Q: Whatís your educational background?

Lee Actor: I have B.S. and M.S. degrees in Electrical Engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and an M.A. degree in Music Composition from San Jose State University. I also spent a year at U.C. Berkeley working toward a PhD in Music Composition

Q: What was the first company you worked for, doing programming?

Lee Actor: My first job out of college in1975 was an engineer with GTE Sylvania, where I was doing real-time programming on some of the earliest all-digital communication systems.

Q: What inspired you to go into game design? Were there any programmers or games that inspired you?

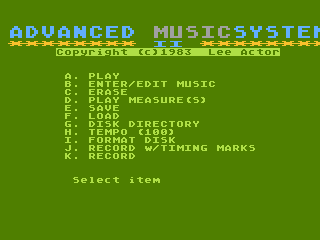

Lee Actor: I had developed Advanced Music System for the Atari 800, through which I met Ed Rotberg, who also had a keen interest in music software. Ed had just left Atari with Roger Hector and Howie Delman to start Videa, a coin-op startup. When we met they had just opened their offices on Lawrence Station Road in Sunnyvale and had no employees. That day Ed offered me a job as a game programmer and after thinking about it for a week, I accepted (I had gone back to school and was then a PhD student in music composition at U.C. Berkeley). I started working at Videa a few months later, thinking if it didnít work out I could always go back to school. I stayed in the videogame industry for almost 20 years.

I always had a great interest in games and had been designing my own from the age of around 9 (no computers, just balls, cards, dice, etc.). When I started in the videogame industry in 1982, the great games such as Breakout, Asteroids, Defender, Robotron, Star Wars, etc. all had a common element which fascinated me: as the difficulty of the game ramped up, with practice the player could continually break through what had previously seemed to be impossible obstacles, seemingly without limit. From a technical perspective, some of the most brilliant work in those days was being done for the Atari 2600, which was excruciatingly difficult to program.

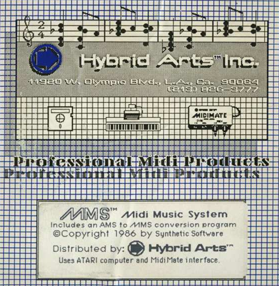

Q: How did Advanced Music System, the sequel (AMS II), and MIDI Music System come about?

Lee Actor: I wrote AMS during the summer between terms when I was studying music composition. I was frustrated with the lack of sophistication in the currently existing music development products for the Atari 800, and I started AMS as a tool for my own use. Eventually it became a product for Atari, and my entrťe into the videogame business. AMS II was a further refinement of the original AMS with additional features, completely rewritten in assembly language. A version of this software became the music development tool for Bally Sente. Gary Levenberg (a co-worker at Bally Sente) and I formed Synthetic Software to develop products in the field of music and sound development. MMS was a MIDI-oriented music development product based on AMS II, and the only program of ours that Hybrid Arts published. Synthetic Software did a few other things, most notably the Atari ST port of SoundDesigner II, Digidesignís predecessor to Pro Tools. Hybrid Arts was a completely separate company we entered into an agreement with to publish MIDI Music System.

Q: For being your first efforts, both Lasercade and Dave Ross' Atom Smasher (aka Meltdown) are very impressive, especially since they're only 4K. Why didn't Videa release either one?

Lee Actor: Lasercade was my first project at Videa. Dave Ross and I were programming Atari 2600 games, involving quite a bit of reverse-engineering, which Dave was particularly skilled at. Unlike Activision and Accolade, whose founders had developed VCS games at Atari, Videaís pedigree was strictly coin-op, so we had to figure out the VCS hardware on our own. Videa did sell both Lasercade and Atom Smasher to Fox. Both were shown at the Winter 1983 CES, and in the wake of Atari's recent immolation (which single-handedly almost destroyed the consumer videogame market) were never released by Fox. My memory is that Atom Smasher was not subsequently sold by Fox to Atari, but several months later, Videa (who had gotten the rights back from Fox) did sell Lasercade to Atari, who also never released the game.

(LEFT) Lasercade; (RIGHT) Meltdown.

Q: Besides Lasercade and Meltdown, was Videa working on other games, or planning to? Was the VCS the only platform they planned to support?

Lee Actor: VCS development was a support activity and arcade games were to be the main thing. Videa only existed for about a year, so only a limited number of products could be developed.

Q: Was Videa basically the home gaming side of Sente?

Lee Actor: No, Videa was the predecessor to Sente, and when Videa was purchased by Nolan Bushnell, it became Sente (first Sente Technologies, then Bally Sente). The main business of Videa was always envisioned to be coin-operated games, and VCS development and other side projects were seen as subsidiary. One arcade game was produced at Videa (Pogoz), though I donít think it was ever released.

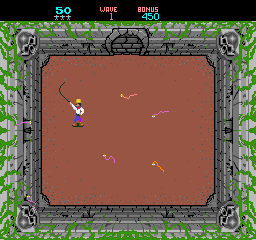

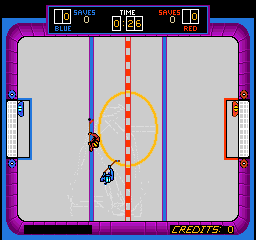

Q: I remember Sente getting a lot of press for their first game, Snake Pit...

Lee Actor: Snake Pit was the first game designed for the Sente System, the coin-operated game industryís first modular game system. It was also the first arcade game to use a dedicated sound board. I was the designer and programmer on the next game we did, Hat Trick, which was Senteís most-successful game (rated as the top-earning software title in Replay magazine for 5 months straight). I also designed and programmed Street Football, which was featured in the 1988 Jodie Foster film, The Accused.

Q: I noticed that most sites list the title as two words, although both the Sente and Bally Sente flyers list it as one word in the descriptions, as does the title screen. Which way is correct?

Lee Actor: I always definitely considered "Snake Pit" to be two words. If you look at the official graphic logo, there is a noticeably bigger space between the "E" and the "P" than between the other letters. It is true that on the title screen graphic the letters are all jammed together; I think probably because it looks better for that particular design. But it should be two words.

The original version says (C) 1983 Sente Technologies" on the title screen. The Bally Sente version is copyright 1984. I honestly don't remember changing the title screen, though I'm sure I did, and I'm positive there were no changes to the game itself.

Q: What was the development process like at each of the companies you worked for? Was your schedule fixed (i.e. 9 to 5) or could you basically come and go as you pleased?

Lee Actor: At Videa/Sente/Bally Sente there was no real fixed schedules; the emphasis was always on getting the work done, not how and when it got done. We spent a lot of time during the normal workday playing videogames, ping pong, etc., but there were plenty of nights, weekends, and the occasional all-nighter when called for. Personally I thrived in this kind of creative work environment.

When Bally Sente closed down for good in 1988, Dennis Koble and I formed Sterling Silver Software to do game development as 3rd party independent contractors (the company was renamed Polygames in

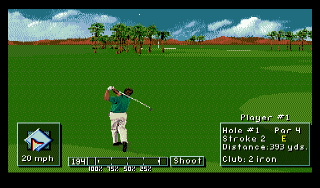

1992 when Sterling Software raised a fuss). Our first project was PGA Tour Golf for Electonic Arts, which was extremely successful and subsequently engendered many sequel products for us, mostly for Sega Genesis (after many years of successful collaboration with EA, they took product development for the PGA franchise in-house, now known as Tiger Woods PGA Tour Golf). We also developed products for Accolade and others, did many arcade-to-Genesis conversions for Atari

Tengen, and the mega-hit Sonic Spinball for Sega. Dennis and I worked out of our home offices for 10 years, which is my favorite working environment. Very flexible, but you work much harder than you do as an employee in any company. In late 1996, Dennis and I, along with Roger Hector, started Universal Digital Arts, a videogame development subsidiary of Universal Studios based in San Jose. As management, we tried to provide the same flexible, creative environment

that we had enjoyed in the earlier days of game development. Whether we succeeded or not youíd have to ask the people who worked there. We worked on several projects at UDA, one of which was ultimately released: Xena: Warrior Princess for the Sony Playstation.

When Bally Sente closed down for good in 1988, Dennis Koble and I formed Sterling Silver Software to do game development as 3rd party independent contractors (the company was renamed Polygames in

1992 when Sterling Software raised a fuss). Our first project was PGA Tour Golf for Electonic Arts, which was extremely successful and subsequently engendered many sequel products for us, mostly for Sega Genesis (after many years of successful collaboration with EA, they took product development for the PGA franchise in-house, now known as Tiger Woods PGA Tour Golf). We also developed products for Accolade and others, did many arcade-to-Genesis conversions for Atari

Tengen, and the mega-hit Sonic Spinball for Sega. Dennis and I worked out of our home offices for 10 years, which is my favorite working environment. Very flexible, but you work much harder than you do as an employee in any company. In late 1996, Dennis and I, along with Roger Hector, started Universal Digital Arts, a videogame development subsidiary of Universal Studios based in San Jose. As management, we tried to provide the same flexible, creative environment

that we had enjoyed in the earlier days of game development. Whether we succeeded or not youíd have to ask the people who worked there. We worked on several projects at UDA, one of which was ultimately released: Xena: Warrior Princess for the Sony Playstation.

Q: Were the titles you worked on assigned, or chosen by yourself?

Lee Actor: When I was an employee, it was more a case of programmers bringing game ideas they were excited about to management and reaching a mutual agreement, at least for programmers with any kind of a track record. As independent contractors, Dennis Koble and I only worked on projects we were interested in.

Q: Do you remember what early or tentative titles your other games had (if any)?

Lee Actor: My games generally got a name at the beginning, which then stuck. Lasercade was probably not the original name for that game, but 25 years later I canít remember what else it might have been called.

Q: With your original games, what was the inspiration for each one? What was the easiest/hardiest part of designing them?

Lee Actor: Iím not sure ďinspirationĒ is the applicable term, though the idea for Hat Trick did come from a simple two-player electronic hockey game I had as a kid, and Street Football is something of an echo from my childhood. But mainly my inspiration was to work on games that were fun. The actual design part was never hard for me; I always focused on making the game as fun as possible. Sometimes there were software bugs or bugs in the real-time interaction between software and hardware that were very challenging to find.

Q: Besides Roger Hectorís help with some of the graphics in Lasercade, did you work with any graphics or sound artists on your other titles? If so, do you recall who helped with what?

Lee Actor: On my coin-op titles at Sente I worked with graphic artists Mark McPhee, Marty French, Bil Maher, and Gary Johnson, and sound/music designers Gary Levenberg and Jesse Osborne. At Polygames we worked with graphic artist Willy Aguilar, plus a number of other artists and sound designers at EA and Sega.

Q: Are there Easter eggs in any of your titles? Do you recall any fellow co-workers that did?

Lee Actor: These started out as in-jokes and eventually became a planned feature and even intentionally ďleakedĒ to the press. Most of my games had something somewhere, but I honestly canít recall them now. While not exactly an Easter egg, the mock-up high score screen of Street Football that I did for the film The Accused contains my initials and those of many of my co-workers (thereís a lingering close-up on it about 2/3 of the way through the movie).

Q: Were there any games or projects that you worked on that ultimately never got released or even finished?

Lee Actor: Team Hat Trick

was a 4-player version of Hat Trick in a cocktail cabinet. On test it did gangbusters in Canada, but due to circumstances I canít recall was never released. But several of us at Sente continued to play the game at work 45 minutes every day for many months.

Lee Actor: Team Hat Trick

was a 4-player version of Hat Trick in a cocktail cabinet. On test it did gangbusters in Canada, but due to circumstances I canít recall was never released. But several of us at Sente continued to play the game at work 45 minutes every day for many months.

When Bally Sente went under in 1988, there were a few of us left working as independent contractors. I was in the initial stages of a 3-D 1st-person spaceship game. Polygames finished half of a high-res golf game for Hollywood special effects company RGA called City Golf before Phillips pulled the plug on the project. Universal Digital Arts had put quite a bit if work into a Playstation game based on the classic Universal Studios monsters (Iím talking about Frankenstein and Dracula, not their upper management).

Q: It's a shame that Team Hat Trick was never released. I've never even heard or seen pictures of it. If the software still existed, it might be possible to emulate itÖ

Lee Actor: Team Hat Trick could be played by 1-4 players, but by far the most fun was 2 human players on each side. Each team had 2 players plus a goalie, and with a human partner you could run plays, pass, screen, etc. It was very addictive. I should have gotten one for myself at the time, but those cabinets are pretty big.

Q: Do you recall any other titles that other co-workers were doing on that were never released, or finished?

Lee Actor: The most prominent one I can think of is Owen Rubinís Shrike Avenger at Sente, a full-motion flight simulator game whose motors kept burning out on test. I think it also made some people dizzy or even sick, and it was deemed too expensive and too much of a liability to produce (Ed.: Howard Delman also worked extensive on this game).

Q: With your programs, were there any features you would have liked to added, or any known bugs or glitches that gave you trouble (or never got resolved)?

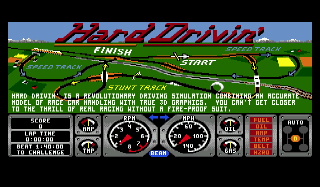

Lee Actor: Adding features is a potentially never-ending activity, and I never worried myself about it. There was usually an agreement up front what the features were, and we kept to the plan. I take particular pride in producing bug-free code, and I donít recall any known bugs in any software Iíve released with the possible exception of Sonic Spinball, which had an extremely shortened development cycle. Come to think of it, there were some polygon-drawing bugs in Hard Driviní that I donít think we were ever able to fully fix. Of course, itís kind of insane to even attempt a 3-D polygon game for hardware that doesnít have bit-mapped graphics (Dennis Koble and I did 7 full 3-D polygon games for the Sega Genesis).

Q: Of all the platforms you've worked with, which one(s) did you enjoy working with the most/least?

Lee Actor: My favorite platform to work on was probably the Sega Genesis, which I did more products on than any other hardware. It was not very powerful, but we had excellent development tools. I always enjoyed working close to the hardware, so the PC would probably be my least favorite platform.

Q: Did you ever attend any industry shows, such as CES or Toy Fair?

Lee Actor: I went to CES almost every year for 10 years, also a number of AMOA (coin-operated games) and later, E3 shows.

Q: What were some of your experiences as a programmer? Any stories or anecdotes from those days that you recall?

Lee Actor:

In 1984, Nolan Bushnell arranged a big press conference/party to announce Snake

Pit, the first game produced for his new company, Sente Technologies, and its

modular arcade game system, the Sente System. As the designer/programmer

of Snake Pit, I took part in these activities, including being photographed with

a large, heavy boa constrictor draped on my shoulders. After the event, I

recall with crystal clarity meeting Nolan in the hallway, where he gave me the

thumbs up and beamed, "Slam dunk!" Unfortunately, after a large pre-sell

and initial promise of success, production problems (failing power supplies) and

the later financial collapse of Pizza Time Theater, the parent company, doomed

Snake Pit in the marketplace.

The most memorable moment of my overall videogame career was the day in early

1991 that Polygames (then Sterling Silver Software) received its first

significant royalty check from Electronic Arts for PGA Tour Gold. That

product had launched our company, and over its two-year development had come

close to being cancelled more than once. With a new production team at EA

to champion the product, internally it changed from ugly wart to crown jewel.

PGA Tour Golf was included as a pack-in with the new IBM PS/2 computers, and was

the beginning of a hugely successful franchise product for EA and Polygames.

That first big royalty check came when we were still unsure if our company would

be successful, and it represented an achievement creatively as well as

financially. There would be many more, and significantly larger royalty

checks coming our way in the future, but the first was by far the sweetest.

Q: I see from your website that youíre also an award-winning composer and conductor. How hard (or easy) was it to segue between programming and composing/conducting? How much did your experiences in writing music programs (or programming in general) help?

Lee Actor: These have really been completely separate (and sequential) careers for me. I did write some music and sound design software during my videogame career, and even wrote a bit of original music for Snake Pit, but Iíve found that writing software, like writing music, requires my full-time attention to do it well. When I ďretiredĒ in 2001, I decided to devote myself full-time to writing orchestral music, and Iíve had a bit of success at it the past 6 years. My third CD will be released by Albany Records in a few months.

Q: Do you still own copies of any of your programs, either as keepsakes, or to show friends or family?

Lee Actor: I have copies of most of my PC and console stuff (not all of which I still have machines for them to run on!), but as you might expect, none of my coin-op stuff. However, I recently found out that Snake Pit, Hat Trick, and Street Football are available on MAME, which is pretty cool.

I do have a header graphic (marquee) and control panel graphic from Snake Pit, and both say Sente Technologies (copyright 1983).

Q: Which of your titles are your favorite, and what types of games in general?

Lee Actor: Iíve always been somewhat partial to sports games, due to the competitive factor. I think the most fun games Iíve done are Team Hat Trick and PGA Tour Golf III for Sega Genesis

Q: Have you stayed in touch with any of your former co-programmers?

Lee Actor: Dennis Koble is still a close friend and we talk regularly. Roger Hector and I have lunch every few months, and Iím still in touch with Rich Adam and Ed Rotberg.

Q: What are your thoughts on how the video gaming industry has evolved?

Lee Actor: Frankly, Iíve been out of the industry since 1999 and have not kept up to speed on things. However, even at the end of my video game career I could see that things were going in a direction that was not to my liking: bigger and bigger development teams and increasing specialization. The creativity and just plain fun from the early days seems to be an ever-shrinking commodity. When I started in the video game industry, the technical capabilities hardware-wise were minimal, which by necessity put the main emphasis in game development on the gameplay and the fun factor. Nowadays, many games exhibit stunning technical achievements in graphics, sound, and programming, but unfortunately seem to have relegated gameplay to a subsidiary role. Hmm, Iím starting to sound like an old fogey, so Iíll stop now.

Footage of Atari VCS/2600 Lasercade:

| GAME | SYSTEM | COMPANY | STATUS |

| Advanced Music System | Atari 400/800 | Atari | released |

| Advanced Music System II | Atari 400/800 | APX | released |

| MMS - MIDI Music System | Atari 400/800 | Hybrid Arts | released |

| Lasercade | Atari VCS/2600 | Videa | unreleased |

| Snake Pit | arcade | Sente Technologies | released |

| Hat Trick | arcade | Bally Sente | released |

| Team Hat Trick | arcade | Bally Sente | unreleased |

| Street Football | arcade | Bally Sente | released |

| Starglider-type game | arcade | Bally Sente | not completed |

| Donít Go Alone | DOS | Sterling Silver Software (for Accolade) | released |

| PGA Tour Golf | DOS, Genesis | Sterling Silver Software (for Electronic Arts) | released |

| PGA Tour Golf: Tournament Course Disk | DOS | Sterling Silver Software (for Electronic Arts) | released |

| Hard Drivin' | Genesis | Sterling Silver Software (for Tengen/Atari) | released |

| Pit-Fighter | Genesis | Sterling Silver Software (for Tengen/Atari) | released |

| RoadBlasters | Genesis | Sterling Silver Software (for Tengen/Atari) | released |

| City Golf | Mac, PC | Polygames (for RGA/Philips) | unreleased |

| PGA European Tour Golf | Genesis | Polygames (for Electronic Arts) | released |

| PGA Tour Golf II | Genesis | Polygames (for Electronic Arts) | released |

| PGA Tour Golf III | Genesis | Polygames (for Electronic Arts) | released |

| PGA European Tour Golf | Genesis | Polygames (for Electronic Arts) | released |

| Pit-Fighter II | Genesis | Polygames (for Tengen/Atari) | unreleased |

| Race Drivin' | Genesis | Polygames (for Tengen/Atari) | released |

| Sonic Spinball | Genesis | Polygames (for Sega- Sega Technical Institute designed it) | released |

| Steel Talons | Genesis | Polygames (for Tengen/Atari) | released |

| City Golf | PC | Polygames (for Philips/Robert Greenberg Associates) | not completed |

| Xena: Warrior Princess | PS1 | Universal Digital Arts (for EA) | released |