Pete Lyon interview

By Ross Sillifant

(2015)

Q: Before I even start on the questions, I have to include a note of personal thanks, as your 16-bit work was bloody legendary, Sir, it really was. You're behind so many ST games my friends and I simply adored, so thank you for everything you did.

Pete Lyon: Thatís great to know. I feel almost embarrassed by this enthusiasm since looking back, the time seems a blur of intense activity and mild panic as I hardly knew what I was doing.

Q: We'll start with the tried and tested approach Pete, if that's okay. Would you be so kind as to introduce yourself to our readers?

Pete Lyon: My name is Pete Lyon and I worked for many years as an artist in the computer games industry. I was born in Liverpool but my family lived in Australia for a few years. I had a Catholic grammar school education and attended Liverpool Art College on the Fine Art Degree course. I suppose Iíve spent my time in the M62 conurbation at various locations but specifically in Leeds, which is where I lived when I was doing my early digital work.

Q: Looking back at your (stunning) Atari ST work, would you mind talking us through how you managed to overcome the limits the ST hardware imposed upon you? By this I mean, whilst you had high-resolutions, and 512 colors to choose from, you must have been restricted by factors like, the limited number of colors you could have on-screen and the 'window/playing area' your graphics were going to be running in. Were these restrictions ever a frustration and cause of some heated debates between yourself and the programmers?

Pete Lyon: In many ways, the programmer dictated what was possible and put the restrictions beyond debate. Often, the way the graphics were handled in the code came right at the outset and were integral to both gameplay and graphic style. The priority was always to fit the images in memory and have the game run glitch-free at a decent speed; very much the programmerís province. I had to find ways of squeezing out details and effects within these parameters.

Q: The reason I ask is, your games always seemed to boast the most wondrous visuals, and you had such a unique, striking art style - visuals were detailed, great use of colors, shading, etc. Any thoughts you have on game design, art packages used, and how the ST itself shaped up would be most welcome.

Pete Lyon: I trained as a conventional artist and had an interest in art history as well as enthusiasm for animation and SF. Iíd been working as a teacher of programming and IT skills, as well as cartooning, but also did a number of commissions as an illustrator and cover artist in the fantasy and SF genres. I was an active fan of science fiction and help organize conventions where I also exhibited paintings. These interests and skills all combined to help when it came to dealing with the exigencies of game graphics

Q:

How did you start working with another ST legend, Steve Bak, along with

musician David Whittaker - the trio was loved by the UK press at the

time, who dubbed you the 'ST Dream Team'. Indeed you 3 simply were real

pioneers, who were seemingly not content to use the ST hardware, but take it

into realms many thought impossible at the time. Was it a working

relationship you fondly look back on?

Q:

How did you start working with another ST legend, Steve Bak, along with

musician David Whittaker - the trio was loved by the UK press at the

time, who dubbed you the 'ST Dream Team'. Indeed you 3 simply were real

pioneers, who were seemingly not content to use the ST hardware, but take it

into realms many thought impossible at the time. Was it a working

relationship you fondly look back on?

Pete Lyon: I look back on the relationship with Steve in mild bafflement - we were chalk and cheese as they say. Iím sure I equally puzzled him, but we had our respective talents and appreciated that. He considered me to be very pretentious and a lefty, whereas I was exasperated by his conventionality when it came to social and cultural issues. He did all the main work, the organization and planning, etc - and I bobbed along with a wry smile or occasional expletive. But we both worked damn hard.

Iíd seen an advert in a magazine wanting artists ,and since I had big dreams as to the future of digital graphics, I jumped at the chance to try and earn enough dosh (cash) to buy a better set of kit. I remember being so hung over when I turned up at his office, I was almost monosyllabic, which probably gave him a false impression of stoicism. Anyway, the job was to do the title screen for a pool game heíd developed. Iíd never used an ST before (Spectrum and BBC Micro I fear), let alone any software, and barely able to focus my eyes. I just sort of drew my hand using the mouse in front of me as I learned what the icons did. This seemed to do the trick, to my amazement.

Q: As an artist of such a high standard, were there ever concerns that your work was to feature in some very challenging ST games, who's difficulty levels might see the player give up, long before they'd seen everything the game (visually) had to offer?

Pete Lyon: When I look back at something like Return To Genesis, the outstanding new visuals each new lever were something of a reward for me getting that far, and the desire to see more drove me on.

Q:

How did you feel when a title featuring your visuals was slated by the press for

gameplay flaws (something you yourself

had no control over)? Were you

ever concerned a poor review might put the general public off from seeing the

fruits of your labors?

Q:

How did you feel when a title featuring your visuals was slated by the press for

gameplay flaws (something you yourself

had no control over)? Were you

ever concerned a poor review might put the general public off from seeing the

fruits of your labors?

Pete Lyon: All of that was effectively out of my control; I just assumed that I found some games difficult because I was so crap at them. I seem to have fairly rapidly been inundated with offers of work which I ill-advisedly did not refuse. In a sense, I did not take what I was doing too seriously, whist at the same time being engrossed by the task and trying hard to do the best I could for each commission. I treated the games as if they were similar to the book covers and didnít engage too much with the content, which I all too often found wanting. I had the idea that eventually Iíd have creative control, and in the meantime, Iíd knuckle down and concentrate on the immediate task.

Q: What can you recall of an early ST game called Tanglewood? It was supposed to be originally based on the cartoon series Willow The Wisp, but licensing fees soon put paid to that idea, and so it became an original title. Some claim it exists...

Pete Lyon: Not as far as I know, but that sounds plausible. Frankly, I never asked. Much of what I had to do was a bit derivative and so I shrugged and tried hard to let such issues of originality pass me by. It may come across as a tad arrogant, but my standards were my own and I just tried to live up to them as much as possible.

Q:

What was your 'relationship' with the UK Press really like? I mentioned

earlier you being named as part of the Dream Team, but I also recall likes of

Computer & Video Games giving Airball 10/10 for the graphics, describing

them as breathtaking. Did such praise ever put a degree of pressure on you, or did you simply draw the visuals you wanted/felt best suited to the

game in question, letting the press make of them what they wanted?

Q:

What was your 'relationship' with the UK Press really like? I mentioned

earlier you being named as part of the Dream Team, but I also recall likes of

Computer & Video Games giving Airball 10/10 for the graphics, describing

them as breathtaking. Did such praise ever put a degree of pressure on you, or did you simply draw the visuals you wanted/felt best suited to the

game in question, letting the press make of them what they wanted?

Pete Lyon: I was usually too busy to read reviews; in truth, I avoided them. When I did read them, they made me anxious and sick, and the bad ones made me feel even worse. It seemed better to go with the illusion that somehow they were writing about someone else.

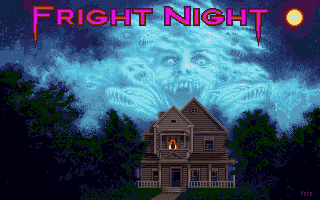

Q: One Amiga title that visually stood out for myself was Fright Night. Rumors had it that there were plans for a campaign game to be released to go with it, more of an adventure game. Can you recall anything of such plans?

Pete Lyon: Again, I cannot recall. I just tried to summon up as many of the tropes of the horror movie I felt were expected. There were fewer restrictions on the graphics, especially as I was now able to approach more figuratively realistic figures. This kept me happy, and I think at this point I was just left to get on with it.

Q: As far as I can tell, the ST version of Fright Night never came out, only the Amiga version. There's an ad for the game that lists the ST version (with a price) and a catalog that simply says the game is coming soon. Can you confirm you worked on an ST version, and do you recall why that version was never released?

Pete Lyon: At that time, I would have been using a PC and DPaint to create the graphics. Any conversion to the ST would have involved mixing down the palette from 32 to 16 colors, which I never did. I really don't know what happened there, whether the conversion was cancelled for commercial reasons or something else. We were all getting involved with other projects and did not work in such an integrated way that I would have been privy to any such considerations. There always seemed so much to do that my attention slipped in a blur of activity. I can't really be of much further help on this matter, I'm afraid.

Q:

As well as working with Bak, you were teamed up with John Phillips for

Eliminator and yet again, it seemed the winning team, with your fantastic backdrops

merged with his fantastic 3-D coding. Did you have a degree of choice of who you

worked with and on what, because you'd rapidly established yourself as 'the' ST

artist at the time?

Q:

As well as working with Bak, you were teamed up with John Phillips for

Eliminator and yet again, it seemed the winning team, with your fantastic backdrops

merged with his fantastic 3-D coding. Did you have a degree of choice of who you

worked with and on what, because you'd rapidly established yourself as 'the' ST

artist at the time?

Pete Lyon: Looking back, I could and should have been more circumspect about who I worked with, but wasnít. Essentially, if I was asked, I felt so flattered that I couldnít refuse, so I tended to try and produce the goods for whosoever turned up. A degree of willful naivety, combined with the novelty of being well-paid seemed to justify a strategy of keeping any creative ambition sequestered.

Q:

These days, a lot of games seem to be about UGC (User Generated content) and

publishers keen to sell us DLC from day 1, yet again here you seemed involved in

pioneering such things years ago. I'm thinking of things like the 2 Goldrunner

scenery disks (early expansion content sold at budget price) and The Airball

Construction Kit. Both seemly designed to extend the life of a product and

deliver greater VFM in the long run.

Would you of liked to have offered up more expansions like this for other

titles?

Pete Lyon: In many cases, it was often refinements of the pre-existing development tools that were offered, for greater profit.

Q: Sticking with Goldrunner, the story is a conversion was at least started for the Commodore 64. Were you involved in any way with that?

Pete Lyon: Nope.

Q: A few titles of yours (Astaroth: The Angel of Death, Amnios, etc) had a very 'organic' look to them - Astaroth in particular seemed very inspired by work of H.R. Giger. Did you let your personal influences seep into your game art? How much control were you given over the look of the games you worked on, during ST/Amiga era?

Pete Lyon: By and large I was given complete control - management and programmers just wanted things to Ďlook goodí and fit in the game and production timeframe and budget. Often a programmer had read a comic or seen a film and wanted something Ďa bit like thatí, but seemed to have little awareness of the context or influences of that which they were recommending as guidance. I found it easier to get guidance like this rather than to try to introduce unfamiliar examples or ideas, which only led to arguments or frustration.

Q: Once the Amiga became firmly established, were you reluctant to carry on working with the ST? Whatever happened to the Amiga game, DDT: Dynamic Debugger that planned to use all 4,096 colors onscreen in HAM mode? I saw the adverts and previews (LINK), and then... nothing.

Pete Lyon: Although I enjoyed the unfussiness and reliability of the ST, I was always keen on getting a larger palette and more memory. On occasion I worked on both platforms, so it was a case of originating images on the Atari and then enhancing them on the Amiga. Once I got hold of a PC, I worked in exclusively on that and then reverse-engineered work for various platforms. It was Debugger that gave me that first experience. With Steve and others, the trick was to use ĎAND/ORí bit logic to update the next Ďframeí of any sprite or background block. The colors were restricted so that their logical numbers could be crunched rapidly to produce the next image. As such, not any particular element was restricted to a bank of 4 or 8 colors that had a simple relationship - all the odd or even ones for example. By carefully organizing my palette and partly duplicating hues, I could simulate a broader range of colors. It worked better on the early games, when they were viewed on TVs and the pixels blurred into one another. My jokey reputation for purple partly derives from this bodge. Thus I resorted to elaborate stippling regimes and had to be careful about which color number I used, otherwise it caused glaring flashing errors or crashes. All this made life difficult for the humble artist. When it came to Debugger, the opportunity to go to the next stage was irresistible, but the restrictions on my color range were even more elaborate and irksome; in order to get things to work, I had to organize ranges and carefully avoid the primary colors that preceded each graduated sub-palette. It was mind-numbing. Well, they couldnít get it to work properly and I ended up having to partly fund the project, which was then abandoned with me fruitlessly knocking on their door asking for explanations and refunds and them being Ďnot iní. Ah! - those were the daysÖ

Q:

You worked on the ST version of StarRay (or Revenge Of Defender) and again,

you seemed very much the man for the job. Was it an easy conversion and were you

perchance involved in the ill-fated conversion to the Konix Multisystem?

If so, any information on the conversion or Konix hardware itself would be

fantastic.

Q:

You worked on the ST version of StarRay (or Revenge Of Defender) and again,

you seemed very much the man for the job. Was it an easy conversion and were you

perchance involved in the ill-fated conversion to the Konix Multisystem?

If so, any information on the conversion or Konix hardware itself would be

fantastic.

Pete Lyon: My involvement was simply to add to and improve a pre-existing game. Actually, I thought the earlier stuff wasnít bad and I confined myself to taking things a little further. In those days, I had little idea how other artists approached their tasks and pretty much made up things 'in vacuo', so it was always useful to see otherís raw material.

Q: As you seemed to get the very best out of Atari's (limited) ST hardware, did Atari ever approach you to work on platforms like the STE/Falcon or their planned 32-bit Panther console, as these seemed ideally-suited for your talents. I'd wager by the time Jaguar was becoming a reality, you'd long since moved on.

Pete Lyon: No, I was seduced by the possibility of using full-color and higher resolutions, which unfortunately led me down further blind alleys and fumbled projects - a victim of my own poor judgement. When I did finally get the message and try and assert myself creatively, I came to the painful realization of how rubbish I was at management and gameplay design. I persevered, and tried to reproduce a close-knit competitive collaboration, similar to being in a band I guess, but the industry was moving on to bigger and more expensive projects. The giant open-plan offices and personal politics were not to my taste - I definitely preferred the role of a freelancer. Along the way, I met some great people, though, and had some terrific times, particularly when working in Manchester. I remember the crazy times with huge affection.

Q: Finally, any unreleased games (any format) you can talk us through? And of course what are you up to these days? There's so much more I'd love to put to you, but I'm more than aware of just how time-consuming these things can be and I'm eternally grateful for any time you can spare.

Pete Lyon:

I set up a company with my good friend and brilliant coder, Alaric, to develop a

game based around a time traveling, post apocalyptic, trash collecting robot,

and sent off versions of the game and accompanying story to various big

companies. More than once Iíve seen ideas of mine reappear later onscreen, which

is disconcerting. Alaric drank himself to death. Iíve had lots of game

concepts but have pretty much given up trying to implement them. The work has

dried up, too, partly because Iíve stopped looking. Maybe itís just that Iím now

regarded as too old and awkward, I dunno. At times I miss it all a lot,

but I was forced to stop. Sadly, I developed what might be called industrial

injuries Ė painful back and limbs resulting from poor work posture and

repetitive stress on the ligatures. Is there such a thing as Ďmouse armí?

Happily, Iím over all that now and am relatively financially secure. I still

work digitally and love what might be called virtual sculpting - building a 3-D

printer from a kit, for example. Currently I enjoy the most amazing and

challenging time, traveling the world for long adventures and learning more about the world and myself. Last but not least, Iím getting re-absorbed

in the disciplines of traditional painting and drawing, and avoiding any

commercial restrictions at all by never selling anything! A cunning plan.

Check out Pete's website to learn

more.