Rex Bradford interview

By Tim

Duarte

(1997)

Q: I came across an article called "The Empire Talks Back", which was published in the January 1983 issue of Electronic Fun with Computers and Games. It is very informative about the creation process of The Empire Strikes Back, the Parker Brothers video game for the Atari 2600. It contains an interview with you and a co-worker names Sam Kjellman. Do you still work with Sam?

Rex Bradford: It's interesting. I work at a place called Looking Glass Technologies now and that article is posted up on a bulletin board in the kitchen. Someone wrote over it, "Where were you in 1983?" The answer for most people I work with is elementary school or junior high.

I did some work with Sam on a few projects a few years ago, but I really haven't been in touch with him since then. So we actually hooked up last on a couple of Sega Genesis games that we did.

Q: How did you get involved with video games?

Rex Bradford: I was in the right place at the right time. I was one of those kids who played a lot of Avalon Hill board games and played a lot of Parker Brothers board games (Risk, Clue, Career, Monopoly). I created a lot of board games that I could never talk anyone into playing as a kid. I went to school at Umass Amherst, and that's where I got into programming computers in the first place, in a children's television research lab in the Psychology department. I spent a couple of more years after school working there doing more stuff, and then I finally decided I was going to seek my fame and fortune as a programmer in the Boston area. I started responding to ads in The Boston Globe and working through a few agencies to find a job. I worked at a low-paying research job, and not having immediate success, I saw an ad in the Globe from Parker Brothers looking for programmers. This was for electronic games - handheld-type games. I immediately applied and thought that this would be a dream come true if I got it. Jim McGinnis at Parker Brothers ended up putting my resume in a drawer the first time around. They had trouble finding people that they liked, and he gave me a phone call. I went for an interview, and I brought a giant stack of listings - all the documents I had written - and basically we hit it off right away. I essentially got hired that day. This was the Spring of 1981. They had not gotten into the Atari 2600 stuff yet; that did not happen until the Fall of 1981.

Q: Did you program any handheld games?

Rex Bradford: None that got released. I did the internal prototype for Electronic Monopoly. Then the VCS/2600 stuff came along and I jumped on that and someone else did the actual production versions. There was only a few of us at the time. Jim M. was running the group. Mark Lesser was the only person he had hired before me and I was the second programmer. Mark was a very experienced handheld guy, and did some more handheld work, so I became the lead programmer of the VCS. I got the opportunity to do The Empire Strikes Back, which was the first game that Parker Brothers released. I was involved with some of the reverse-engineering effort as well. I wrote the 6502 disassembler that we used on the PDP-11. I worked with Jim M. and other people to do experiments and software to verify what the hardware people were figuring out from tearing apart the chip.

Q: Did you use the same equipment as Ed English?

Rex Bradford: Yes. Ed was the next person who was hired - possibly a few months after I was.

Q:

With Empire, what input did George Lucas (creator of Star Wars) have in

the game?

Q:

With Empire, what input did George Lucas (creator of Star Wars) have in

the game?

Rex Bradford: I certainly had to have their approval. When the game was partially complete, I took a trip out to CA and didn't meet George Lucas but spent some time showing the game and talking with some of the heavyweight graphics guys. These were the guys that got the special effects in the Star Wars movies, created, and went on to form PIXAR (creators of the Toy Story movie). It was quite a kick to see those guys. They weren't involved, though. They were interested in talking about the basic design ideas and direction. They were able to talk about the game as a game. I had their approval, and that's about as far as it went.

Q: Did Lucas provide any models or tools, or any inspirational items for you to help you in programming the games?

Rex Bradford: No, the VCS/2600 is at a level where you could not get that kind of detail. The look of the walkers was probably the most complicated thing in the game. Any talented artist could create them from just looking at them on the TV screen.

Q: Did you have any input in the 3 other Star Wars games - Death Star Battle, The Arcade Game, or Ewok Adventure?

Rex Bradford: Ewok Adventure was never published, right? That one is interesting because I saw that game at an unpublished VCS game party where everyone brought a game that had never been released. Larry Gelberg brought that game. We all got to play these unpublished games and it was a lot of fun.

I was not involved in Death Star Battle. Ray Miller wrote that game. It may have some overlap, but I think that project started around the time that I left Parker Brothers.

Q: Are you a Star Wars fan and were you in 1981 when you were designing the game?

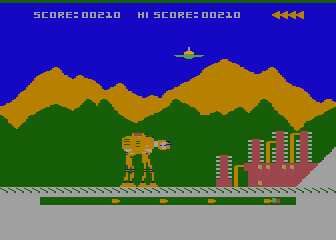

Rex Bradford: I've seen each of the 3 movies 10 or 11 times, so I think I qualify. When Star Wars came out in 1977, it just blew me away. It was the kind of movie both in terms of special effects and just even the fact that there wasn't much science fiction that really grabbed you around at that time. I just ate it right up. The Empire Strikes Back is my favorite movie of the 3 of them by far. It was a real treat to work on a game based on it. There were a lot of things that we would have loved to put into the game, but with a system like the VCS, there are constraints - the biggest of which was in fact there was supposed to be a power generator. We never figured out how to put it in there visually because of the way the sprites and missiles were being used. The other thing we talked about but never developed a concrete plane to do was roping the walkers' legs and making them fall to the ground. That would have been fun to do. I think if I was doing that game now, I could have gotten at least the power generator in and a few other things. We were just learning at that time. I was proud of where we ended up with that project. We knew nothing when we started, and it had to be done in a reasonable amount of time. It was quite a job getting the score done with sprites instead of the old, blocky numbers that Atari was still doing at that point in time. We took a peek inside a few Activision cartridges to get some of the tricks.

Harold Siegmund made an unofficial version of The Empire Strikes Back for the

Atari 800 in 1983 that incorporates some of the ideas Rex didn't have a chance

to include in the VCS version, such as a power generator and being able to run

underneath a walker and take it out with a bomb.

Q: Do you realize that the Empire Strikes Back and Jedi Arena cartridges have become valued as collectibles to Atari 2600 collectors as well as Star Wars merchandise collectors?

Rex Bradford: That's interesting because I remember when I saw them being sold for $4.95 with a $5 rebate that Parker Brothers was offering in 1984! They were essentially free. If it wasn't for sales tax, you could have made money buying them! Can you tell me what my games go for these days?

Q: Well, Jerry Greiner's Guide to the Classic Video Games values Empire at $7 and Jedi Arena at $8; Death Star Battle is $10, and The Arcade Game is $40.

Rex Bradford: Give me a call when they reach $1,000 for I have a few spare copies here :)

Q: When one thinks of Parker Brothers, board games come to mind. Did any of the non-video game management have any involvement in your work?

Rex Bradford: Oh, they certainly did. It was a kind of interesting place that way. Parker Brothers is a very old, traditional "Yankee" company, and until we arrived on the scene, just about everybody in the company was in three-piece suits. It was quite a culture clash. We were in the corporate office in Beverly, MA up on the top floor. I'm amazed it worked as well as it did. I think a lot of people in the company looked at us like we were from another planet. They just shook their heads and figured, well, if we're going to be in this business, I guess we've got to do this. There wasn't animosity per se, but it was just two different world in one building. Rich Sterns was the Vice-President there and the guy who "sold" the company on pursuing the video game market. He was a high-level manager who was very keen on these games. He was the driving force in the company behind getting the resources, making sure the company was doing several games, marketing them, and putting a big effort into it. It certainly paid off for them for a few years. Parker Brothers got cold feet after the big VCS crash. They have had their "one toe in the water" several times, but never got back into the business in a big, big way. But they certainly had both feet firmly planted at the time. The primary involvement of the management and marketing department was picking which games were to be done, and that's the thing that ultimately made me end up leaving the company.

Q: And you had no say in the matter?

Rex Bradford: Our opinion might have been asked once in a while, but the decision that we are doing a Strawberry Shortcake game or a Spider-Man game all came down "from the top".

Q: So it wasn't until you joined Activision that you could take on an original design...

Rex Bradford: Yes. Activision basically said, "Here's a computer. See what you can come up with." If anything, it was too freeform. I didn't get a game published there. I guess that's the downside of that approach.

At Parker Brothers, once we knew we were doing a game, and the basic parameters were laid out, I had a lot of flexibility in carrying out that game. So, it wasn't like there was a spec dropped down or anything.

Q: Did they give you a deadline to complete the game?

Rex Bradford: I forget how the timeframes were laid out, but in my case it wasn't a problem. The timeframes were reasonable. In general, for something like a 2600 game, it was a lot more predictable compared to software projects now where you have 15 people working on it.

Q: It's funny most of the programmers that I interview mention this - back then it was just one person primarily creating the game and today it's a team effort where someone does the graphics, someone does the music, etc.

Rex Bradford: I am now running a project that has a dozen full-time people working on it. It's like night and day.

Q: Although, when I read that Electronic Fun article, Empire had to be one of the first team efforts for the 2600 since Sam Kjellman took part in it as well.

Rex Bradford: Sam was primarily responsible for design.

Q: And he is pictured in a suit!

Rex Bradford: Yes, he was. He was straddled between both worlds. He was at Parker Brothers before me, doing board game design, and wore a suit because everybody had to, until the "video game crazy people" showed up. At the same time, he was a very creative, personable person. I found working with him enjoyable and he was full of good ideas. He wasn't like a marketing drone talking to me or something like that. We worked well together. I participated a lot in the design, partly because on systems like the 2600, somebody who is not a programmer can't really design a game because there is no way they could understand all the constraints of what they are working under. So we worked together on the level of me giving him feedback on the level of constraints, and both of us working together on what we should do to make the game fun. He did some of the artwork as well, like the walkers in particular. To the extent of where you need an artist for a 2600 game, he was the artist. With a lot of VCS/2600 cartridges, because the artwork is so crude, the entire game was usually done by one person. That wasn't quite true for Empire. The nature of it was that it was just a part-time job for him, and a full-time job for me.

Q:

What about the game Jedi Arena?

Q:

What about the game Jedi Arena?

Rex Bradford: It was never really a giant success, and I can probably take responsibility for that. The original idea for that game was to have that ball out there floating around between the two Jedi Knights, but you would be using magnetic forces off of the saber to control the ball and try to make it go careening into your opponent. That was the fundamental, original concept. I played around with that for a couple of months and was never able to get the feel of that working properly. I couldn't figure out a way to make two players with sabers trying to magnetically control the ball work. Finally (and this was actually a big 'to-do' at Parker Brothers), I made the decision that this was not going to work. I wanted to turn this into a game where instead you try to shoot laser sparks off of that and sort of have a Breakout effect - have walls of protection around each player, and just try to break through and get the other player. There were some serious issues where some of the people in management said, "Who on Earth is this kid that we got programming this game that is going to decide that we are not going to do what we thought we were going to do and he wants to do something else?" Fundamentally, Rich Sterns came down and talked to me and I explained to him what I thought about it and he said, "Ok, then that's what we are going to do." For better or worse, it worked out. I think the game was not working at all the way it was and the way it ended up... well, it's probably not the most exciting VCS game in the world, but it was playable and at least some people enjoyed it. It wasn't a big seller like Empire.

Q: Did you have any involvement in the Intellivision version of Empire?

Rex Bradford: No, I wasn't involved in any of that.

Q: What was the name of that company that you later started?

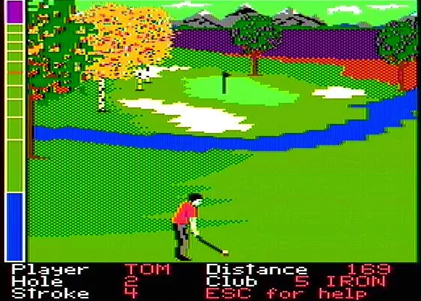

Rex Bradford: Microsmiths. In early 1984, it was with a couple of other people I had worked with before. One of them was Charlie Heath, who worked at both Parker Brothers and Activision with me. The third person was Ray Miller, who I knew from Parker Brothers, although he was not part of the Activision group. Ray only worked with us for one project, and then left to go on to do other things. He is now Vice-President of Alias Research and has certainly gone a long way. So Mark Lesser, who I worked with at Parker Brothers, came in and became the second "third" Microsmith. He, I, and Charlie were together for many years. Microsmiths was a long and varied career. Our biggest success was a game that I wrote in 1985 and published in early 1986 called Mean 18. It was the first 3-D golf game (Ed.: For home systems. Sega released the arcade game Crown's Golf in 1984). At Microsmiths, what we did was a combination of original designs and "ports" of games for other publishers from one game system to another. While doing that work, I wrote Mean 18 on nights and weekends in my spare time just as a labor of love, because I had always been a golf fanatic and wanted to do a computer golf game. I went to the CES show in January 1986 with a nearly-completed game of Mean 18 and Accolade among other companies were extremely interested in it. I struck a deal with them, finished up the game, and they published it and that was a very big game for several years (Ed.: A prototype version for the Atari 400/800 was found).

We did many other projects. For better or worse, we were so into reverse-engineering and working on different systems that we ended up splitting from project to project. We did projects on the Commodore 64, Apple II, Sega 8-bit, Sega 16-bit, Nintendo, PC, Amiga, and Atari ST. We had a lot of fun doing those things, but it basically caught up with us in the long run. By the late 1980s, we were not doing as well as where we had hoped to be by that point. We did fine for a number of years and made a good living, but in 1990, we started doing Sega Genesis work and in 1991 and 1992, we were not clear on where to go from there, and the game business was getting to be a bigger business at that point. More people were on the projects, and the projects were more expensive to do. For a variety of reasons, we just never made that transition and started doing other freelance and contracting work. In 1992, I started doing some freelance work for Looking Glass Technologies. Mark Lesser did a sub-contract project through them - John Madden Football for the Sega Genesis. That ended up being the beginning of the end for Microsmiths. I finally shut it down last year and I am now running a project at Looking Glass Technologies as an employee there.

Q: What are you doing at Looking Glass?

Rex Bradford: We basically do high-end 3-D PC CD-ROM based games. The company sort of got launched with a game called Ultima Underworld, published by Origin. My most recent project is British Open Golf.

Q: What advice would you have for someone looking to get into the video game business?

Rex Bradford: First of all, it has opened up to a lot more people than just programmers - graphic artists, musicians, designers. Start with seeing if you can become a beta-tester for a game company. It's good to have enthusiasm and knowledge. As for programming languages, learn C and C++ if you can. You will also have to have the commitment to work hard. There is a lot of competition out there.

Rex also wrote a book called

Real Time Animation Toolkit in C++.

Ed Temple, Rex Bradford, and Ray Miller at Laura Nikolich's 2006 Parker Brothers

reunion party, looking at Rex's book.

Rex Bradford at Laura Nikolich's

2006 Parker Brothers reunion party.

For more information about Rex, see GDRI's page.

| GAME | SYSTEM | COMPANY | STATUS |

| Electronic Monopoly | handheld | Parker Brothers | unreleased |

| Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back | Atari VCS/2600 | Parker Brothers | released |

| Star Wars: Jedi Arena | Atari VCS/2600 | Parker Brothers | released |

| Kabobber | Atari VCS/2600 | Activision | not completed |

| H.E.R.O. (by Charlie Heath) | Apple II | Activision (Microsmiths) | released |

| Pitfall II: Lost Caverns | Apple II | Activision (Microsmiths) | released |

| Mathmatics Unlimited | Apple II | ||

| Little Computer People | Atari ST | Activision (Microsmiths) | released |

| Mean 18 | DOS, Apple IIGS, SMS, Genesis, Atari 7800, ST, Amiga, Mac | Accolade (Microsmiths) | released |

| Counting Parade | C-64 | Spinnaker (Microsmiths) | released |

| Sum Ducks (by Ray Miller) | C-64 | Spinnaker (Microsmiths) | released |

| Drac's Night Out | NES | Parker Brothers (Microsmiths) | unreleased |

| King's Quest: Quest for the Crown | SMS | Parker Brothers (Microsmiths) | released |

| Beanball Benny | Genesis | Nuvision (Microsmiths) | unreleased |

| Bimini Run | Genesis | Nuvision (Microsmiths) | released |

| Swamp Thing | Genesis | Nuvision (Microsmiths) | unreleased |

| Jack Nicklaus' Power Challenge Golf | Genesis | Accolade (Microsmiths) | released |