Warren Robinett interview

By Russ Perry Jr.

(1992)

Warren Robinett truly made a name for himself, whether it was from his ground-breaking programming efforts at Atari, or with co-founding The Learning Company, or his later work with virtual reality and his contributions to NASA. But for most classic video gamers, his Adventure game set new standards for both the Atari VCS and role-playing video games in general. Between having multiple (linked) screens to popularizing hidden "Easter eggs", Adventure is quite simply the most influential VCS game of all time. Players were charged with the quest to find an enchanted chalice that has been stolen by an evil magician and hidden somewhere in the kingdom, and return it to a golden castle. The designer was a fan of the mainframe game, Colossal Cave, and decided he could make a graphical equivalent. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Q: What games did you design for Atari?

Warren Robinett: In order, Slot Racers, Adventure, and BASIC Programming:

Q: Did Atari assign the games to you or did you have your own ideas?

Warren Robinett: They didn't assign games. When I worked there, what they told me was, "Your job is to design games." And that was it.

Q: Where did you get the idea for Adventure?

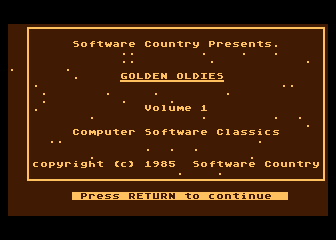

Warren Robinett: I started working on Adventure in 1978. The original computer text adventure had sort of come on the scene at that time. It's the original from which all subsequent adventures are derived. It's on a disk by Electronic Arts called Golden Oldies - Volume 1. You should check it out. The idea for Adventure for the 2600 came from this text adventure.

After finishing Slot Racers, my first game, I was thinking about what to do next. I wanted to do a video game version of the text adventure game. There's an interesting story behind Adventure. George Simcock, my boss at the time, said that it was impossible to compress a 100K text adventure game into a game for the 2600. He also thought all creative ideas should come down from the top of the company, and that's how Atari worked. He told me not to do it, but I did it anyway.

Adventure's multiple rooms was a pretty big innovation. Up until then, video games operated in one screen, in one plane. Having the game go room to room gave the player a much bigger space to have action in.

Q: How did you get the idea for the secret room?

Warren Robinett: There was a group of about a dozen of us that were game designers/programmers at Atari. We were all getting paid salaries with no royalties from our games. Atari was making hundreds of millions of dollars from the games. It was neat to get paid to make video games, but we were anonymous. Once Atari started making an incredible amount of money, we had to get something out of it. I thought of it as putting my signature on the game, just as a painter would sign his name on the corner of a painting.

I also thought of it as a secret message. There was a time when people were listening to songs by The Beatles for secret messages. It was like The Beatles had written this message in the record, which you could only hear if you played the record backwards! I thought I was doing a secret message in a video game.

Q: Are there secret messages in any other of your games?

Warren Robinett: No, just in Adventure. These programs are pretty obscure, so nobody's going to go through your program with a fine tooth comb to look for secret messages. I think it wasn't obvious when people could play the game and not figure it out. When it was a prototype, I thought that if I told anyone, rumors would spread that there was something in the game. I kept it to myself for a whole year, and believe me, it wasn't easy. I didn't even tell my office mates at Atari. If I couldn't keep a secret like that to myself, how could I expect it of them?

Q: I heard a rumor that there was a purple dragon and a Wizard in Adventure. Is there any truth to that?

Warren Robinett: No, none whatsoever.

Q: How was the secret message discovered?

Warren Robinett: Once I completed the game and handed it over to them, Atari replicated it into a couple hundred thousand cartridges and distributed it all over the country. I left Atari not too long after I finished the game, and it took a while for it to get marketed. I returned to California a year later, and Adventure was already out there. Atari had sold approximately 100,000 Adventure cartridges and it was played by kids all over the place. Some kid in Salt Lake City, Utah, discovered the room. He wrote a letter to Atari, explaining exactly how to uncover it (Ed: Here is a copy of the letter, courtesy of Warren). That was the first anybody at Atari knew about it.

Q: Did you inspire other designers to do it?

Warren Robinett: I didn't work at Atari anymore, so they couldn't fire me. I went out with some of the game designers and I told them the story. I looked around the table and I can remember seeing a little gleam in all their eyes. They were thinking of how they were going to do it in their games.

Q: Why did you leave Atari?

Warren Robinett: I didn't get along very well with George Simcock. George did not understand what was going on at Atari at all. He didn't like me and gave me bad reviews on my employee evaluations.

The company wanted a Superman game and I didn't want to do it. After about a month or two, John Dunn, another programmer at Atari, volunteered to take my code - my Adventure code - and turn it into Superman. But, for a year and a half, I really worked hard making games.

Q: What did you do after leaving Atari?

Warren Robinett: I got a backpack and went to Europe. About a year later, I returned to California and met a woman named Anne Piestrup.

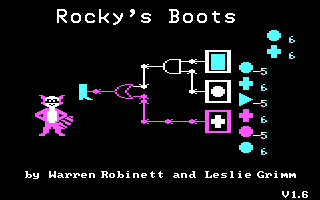

Anne received a grant from the National Science Foundation to make computer games to teach math to grade school children. Anne, another woman, and I created some programs on an Apple computer for about a year and then we started a company called The Learning Company. When I was a part of The Learning Company, I did a program called Rocky's Boots - it's well-known in some circles.

Warren Robinett: I got a backpack and went to Europe. About a year later, I returned to California and met a woman named Anne Piestrup.

Anne received a grant from the National Science Foundation to make computer games to teach math to grade school children. Anne, another woman, and I created some programs on an Apple computer for about a year and then we started a company called The Learning Company. When I was a part of The Learning Company, I did a program called Rocky's Boots - it's well-known in some circles.

Q: Now you're doing virtual reality research. Can you explain what that is?

Warren Robinett: Experientially, virtual reality is like a big video game you can get inside of. From the hardware point-of-view, there's a helmet you put on that has two displays to generate the stereoscopic, 3-D image. A little position and orientation ranging device called a tracker determines when you turn your head or turn around. This allows a sensation that surrounds the player in a computer-generated world. When you turn your head, the computers knows and regenerates the graphics in that direction.

Q: Do you think virtual reality will be very important to the video game industry in the future?

Warren Robinett: Yes. I have a feeling that kids who like video games will go berserk for a 3-D game they can get inside of.

Q: Can you make a prediction on when they'll be coming to the home?

Warren Robinett: It's hard to be accurate when making predictions, but I'm thinking it could happen in 10 years. The question is whether or not it can be done cheaply. If a system costs $10,000, not many will sell. A system that costs $500 is something that people will have the money to buy.

Q: Do you still own an Atari 2600?

Warren Robinett: Yes, but I don't play it very often. Every now and then I take it out to show people what games I created.

Q: What games do you enjoy playing?

Warren Robinett: To tell the truth, I never played video games much. It was more fun to design them.

Q: What were some of your experiences working for Atari? Any stories or anecdotes from those days that you recall?

Warren Robinett: I remember working some very long days - 12 or even 15 hours - this was when I was figuring out if I could do Adventure as a video game in 1978 - and then, totally zoned out mentally, I had to ride my bike home 13 miles from Sunnyvale to Menlo Park. It was usually after midnight - few cars out as I rode past Moffet Field and through Palo Alto - but I kinda got a second wind mentally with my legs and heart pumping, and so I was solving the next set of design and coding problems pumping down the road. Sometimes I really ran out of energy about halfway home. There was an all-night store on Middlefield where I could get a big slab of chocolate. Once when blackberries were on the bushes along the backside of Stanford, I was only a mile from home, but I was so hungry, I stopped my bike and rooted through the berry bushes like an old bear, berry juice on my hands and face.

Here's a video of the secret room in Adventure:

More details can be found in the Easter egg entry for the game. A map for Adventure can be found in the Map section.

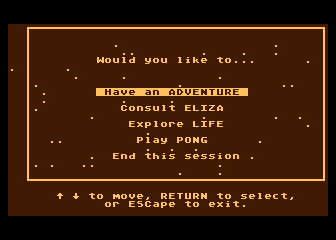

Warren had started working independently on a sequel to Adventure called Elf Adventure. Here are some screenshots from the only known prototype:

He also wrote a book called "Inventing the Adventure Game: The Design of Adventure and Rocky's Boots" which can be found in the Book section.

For more information on Warren's career, check out his website.

| GAME | SYSTEM | COMPANY | STATUS |

| Slot Racers | Atari VCS/2600 | Atari | released |

| Adventure | Atari VCS/2600 | Atari | released |

| BASIC Programming | Atari VCS/2600 | Atari | released |

| Boomerang | Atari VCS/2600 | independent | not completed |

| Elf Adventure | Atari VCS/2600 | independent | not completed |

| Lemonade | Atari VCS/2600 | independent | not completed |

| Rocky's Boots | Apple II | The Learning Company | released |