Do The Donkey Kong

By Scott Stilphen

*Thanks to Greg Bendokus and Ross Sillifant for helping with the article.

It's summer 1981 and I'm at my favorite

local arcade. As I walked in, I saw a new game, front and center.

There's a small crowd around it, and at first I couldn't see what the name of it

is. When I finally saw the marquee, my first thought is, what a strange

name

for a game. As I caught glimpses of the screen, the Kong part made

sense, as the game depicted what looked like a giant ape climbing on to p

of

a building carrying a woman ala King Kong, but I didn't get the Donkey

part. There were no donkeys in sight (in the game, that is. The

arcade was another matter) and the ape wasn't doing anything particularly stupid but rather

aggressively kidnapping someone and attacking the player with barrels. For

years it was thought the name was originally meant to be Monkey Kong, but

a

misunderstanding with the name due to a poor Telex (pre-Fax tech) message

between Nintendo and the company printing the cabinet artwork led to the "M" in

Monkey being misconstrued as a "D". Another version of the story

blamed a mistake in the translation process from Japanese to English.

Donkey Kong's developer Shigeru Miyamoto denies both of these, as he

claims naming it Donkey Kong was meant to convey "stupid ape" or "stubborn

gorilla" (as in 'stubborn as a mule'), depending on which interview you read.

American cartoons at the time sometimes depicted a character doing something

stupid and 'transforming' into a donkey, or jack-ass as more commonly labeled.

Whatever the true origin story is, it was and still is a weird name.

p

of

a building carrying a woman ala King Kong, but I didn't get the Donkey

part. There were no donkeys in sight (in the game, that is. The

arcade was another matter) and the ape wasn't doing anything particularly stupid but rather

aggressively kidnapping someone and attacking the player with barrels. For

years it was thought the name was originally meant to be Monkey Kong, but

a

misunderstanding with the name due to a poor Telex (pre-Fax tech) message

between Nintendo and the company printing the cabinet artwork led to the "M" in

Monkey being misconstrued as a "D". Another version of the story

blamed a mistake in the translation process from Japanese to English.

Donkey Kong's developer Shigeru Miyamoto denies both of these, as he

claims naming it Donkey Kong was meant to convey "stupid ape" or "stubborn

gorilla" (as in 'stubborn as a mule'), depending on which interview you read.

American cartoons at the time sometimes depicted a character doing something

stupid and 'transforming' into a donkey, or jack-ass as more commonly labeled.

Whatever the true origin story is, it was and still is a weird name.

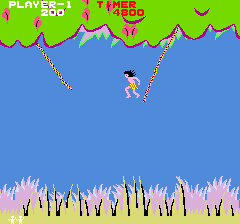

The game's building wasn't the smooth concrete structure of the Empire State building but an unfinished structure comprised of different sections of steel girders, the lattice visual appearance of it being more visually appealing than solid beams would have. The buildings inhabitants were cartoon-ish in appearance - a large ape that jumps around waving his arms and occasionally rolling and throwing barrels down at you, a woman in a pink dress yelling "HELP!" over and over, and a construction worker in red and blue overalls and a red hat. I had only seen 2 different screens in the game, the ramps and rivets, with the rivets screen looking more like a traditional building. The game looked and sounded awesome and offered the ability for the player to jump, which was new. Also new was the fact that you weren't just shooting aliens and monsters or collecting money and valuable items - you now had to rescue somebody! For a mere quarter, I can be a HERO! Well, it was a step down from being the defender of a planet, but it was a new motivation to play... as if I needed any.

On my next visit to the arcade, I had a chance to play it, and my experience matched my initial thoughts. Only years later could I articulate just how well the game was designed and programmed. I thought it was amusing that the entire building would remain standing as long as a single rivet was left in place. I wondered how it would have looked and played if the building had started to partially collapse once you started removing rivets, but that was certainly a limitation of the hardware (in 2015, John Kowalski would create a modified version of the game called Donkey Kong Remixed which featured this very idea on the rivets screen). After that, seeing the elevators screen for the first time was another welcome surprise, making me wonder just how many different screens were in the game. Quite some time would pass before I saw the 4th screen, which was commonly - and incorrectly - referred to by everyone I knew as the "pie" screen. Pies? On a construction site? Sure, and the burn barrel in the center of the screen is for baking them, right? Over 40 years later, and I still see references to them as pies. These aren't pies you want to eat because they're concrete... unless you want to turn your stomach into a hardball. The game's flyer also has an interesting caveat in that it mentions Mario must dodge plummeting beams and exploding barrels, and the flyer's artwork shows burning barrels rolling down the ramps, neither of which are in the game.

Nintendo's Donkey Kong. The cabinet refers to the player as Jumpman, but the flyer refers to him as a

carpenter. Riveter would have

been more appropriate, considering this

is an unfinished steel structure and the only wood found is in the barrels Kong

is throwing down.

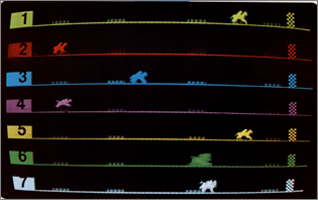

Besides the obvious influence of King Kong, Donkey Kong actually borrowed some idea from a few earlier games. Atari's 1975 Steeplechase involved horses running down a track with players having a single control - a jump button - to navigate their horses over barriers. Nichibutsu's Crazy Climber was released in October 1980 and gave players 2 joysticks to maneuver your climber up the outside of 4 different buildings and dodging various dangerous obstacles and animals. You have a limited amount of time to reach the top of the building. 3 of the 4 buildings have pieces of steel girders raining down upon you. King Kong himself is hanging out on 2 of the buildings, looking to punch you from it. Universal Company, Ltd's Space Panic was released a month after Crazy Climber and featured 5 horizontal platforms with different configurations of ladders between them. The player is pursued by space monsters that must be killed by digging holes into a platform, waiting for one to fall in, and then quickly burying it before it can get out.

(LEFT) Atari's Steeplechase; (CENTER) Nichibutsu's

Crazy Climber; (RIGHT) Universal's Space Panic.

There have been several articles and books covering the details of how Donkey Kong was created, and the subject is a worthwhile rabbit hole to fall in (check out this 2011 Gamasutra article for starters), but I'll try to be brief in my summary. Nintendo wanted to export their arcade games to the U.S., under their Nintendo of America subsidiary, to repeat the success they had with them in Japan. One of their early efforts with this was a shooter called Radar Scope. Some 3,000 machines were shipped to the U.S. in 1980, but thanks in part to another Japanese export called Space Invaders, American gamers were inundated with shooters, with arcades full of variations of the slide-n-shoot theme the likes of which hadn't been seen since the days of Pong. The result was slow Radar Scope sales, leaving some 2,000 machines sitting in storage. A new game was needed if Nintendo's situation was going to be salvaged.

Nintendo's CEO Hiroshi Yamauchi tasked young cabinet art designer Shigeru Miyamoto with designing a replacement game to use the same hardware with the idea of converting the unsold machines. Head engineer Gunpei Yokoi and a budget of $267,000 were allocated to the project, and Ikegami Tsushinki Co., Ltd. was subcontracted for $8k to program the code based on Miyamoto's design (Ikegami also developed Radar Scope), with the plan to have the game completed by mid-June. The hardware was designed by Masayuki Uemura, whom Yokoi had recruited in 1972.

Miyamoto started at Nintendo in 1977 and worked on the graphics artwork for Radar Scope and Sheriff as one of his first projects (it's worth noting that Sheriff might be the first game to show a damsel in distress, as shown between rounds). Miyamoto drew on American culture for inspiration from stories, movie, comics, and cartoons - Beauty and the Beast, King Kong, and Popeye. The game was originally developed to be based around Popeye. In late March 1981, Miyamoto proposed the game design for what he called "Popeye's Beer Barrel Attack Game" (LINK). It was a single-screen game involving a construction site that used a 4-way joystick.

A 1979 Hanna-Barbera cartoon called Building

Blockheads featured King Features Syndicate's characters Popeye and Olive Oyl

competing with Bluto

to build the world's tallest building. Objects such

as rivets, hammers, cement mixers, and cranes carrying steel beams are depicted.

Miyamoto's early concept sketch for Popeye's Beer Barrel

Attack Game. One notable difference is, instead of hammers, there's cans

of spinach.

Nintendo then looked into possibly licensing the 3 main characters (Popeye, Olive Oyl, Bluto) for use with the game, but when that fell through, Miyamoto redesigned the characters.

2 more early sketches, this time with Bluto

replaced with Donkey Kong.

Jumping wasn't originally part of the design, as the original idea was to climb ladders to avoid the barrels, and the button was used to control the hammer, but he later decided to include the ability to jump over objects by pushing up. This was later changed to using the button to jump over barrels and made the use of the hammer automatic. Miyamoto also came up with the opening and closing themes to the game. Sound engineer Yukio Kaneoka came up with the other musical pieces, and Hirokazu "Hip" Tanaka (AKA Chip Tanaka) came up with the sound effects. The design was expanded to show other sections of the building. The programming team at Ikegami Tsushinki Co. complained that having a game with 4 screens was like creating 4 separate games.

When the game was completed, new cabinet artwork was created with plans to initially release it in Japan (on July 9th, 1981), before sending it to the U.S. (July 31st, 1981). It soon became the highest-grossing game in Japan in 1981, and it was the top game in the U.S. in 1981 and 1982. A total of 132,000 machines were sold worldwide, with some 85,000 being produced within the first 8 months of release. It was a monster success to be sure, and with the potential profit involved, sequels, knockoffs, and merchandising followed. As with Pac-Man the year before, Donkey Kong's popularity quickly spread with magazine articles, strategy books, stickers, toys, cereal, and eventually home versions. The cereal's "crunchy barrels of fun" weren't exactly that but rather particularly nasty-tasting stuff with sharp edges. If you're wondering what it tasted like, it was basically the same as Cap'n Crunch.

There were 3 stand-alone strategy books, and probably a dozen

'compilation' books that offered strategies for Donkey Kong and other games.

Topps packs of cards, stickers, and gum were the playground currency of grade

schoolers everywhere.

Ad for Ralston Purina's Donkey Kong cereal. Also known as "Purina

human chow". Ralston Purina was more known for

making pet food

(Nestlé now owns them). I'd sooner eat dog

food than give that cereal to my dog.

(LEFT) Some boxes of Donkey Kong cereal included a chance to win your own Donkey

Kong arcade machine!

(RIGHT) CBS Saturday Supercade (1983-84)

featured characters from several popular video games at the time, including

Donkey Kong.

Since the earliest days of the video game arcade business with Pong, every time a successful video game came along (Space Invaders, Asteroids, Galaxian, Pac-Man, etc), there were people looking to ride on someone else's coattails, and it was no different with Donkey Kong. Donkey Kong combined 3 important features that at the time weren't common and instantly popularized them - the ability to jump over things, a 'world' comprising of more than one screen, and a storyline as told by cut scenes or animations. By the end of 1981, the platform genre was what everyone wanted, and the next few years would see several companies rushing to meet that demand, with mixed results. Before I cover some of the arcade and home clones and knockoffs, I have an amusing aside to one particular variant - Congorilla.

Congorilla arcade game and manual. See? They're not stealing

from King Kong or Donkey Kong or any Kong. There's nary a Kong in sight!

I

don't see how simply changing the character from an ape to a gorilla changes anything,

besides borrowing from Mighty Joe Young this time around, and

neither did the judge.

There was a local bar/restaurant near my house called Emma's on the Trail. I had been there for dinner once with my family a few years earlier (and we had takeouts from there a few times afterwards but that was it), and remember the place wasn't very busy and looked rather drab. Emma's had been one of the go-to places back in its day, as the owner, Billy Emma, was one of the first in the area to bring in entertainment. The parking lot is larger than the building, so it must have been something back then, but by the early 1980s, its days were numbered (it would be out of business a few years later). Anyway, jump(man) to 1982 and video game mania is running wild, especially for me. Donkey Kong is the new king of the video game world, but my trips to my favorite arcade were limited to about once a month. My family had moved a good 15 minutes from town, and the area was more wooded/country. Biking back to town where arcade games were more prevalent wasn't an option (and believe me, I thought about it). I owned an Atari VCS as did a few friends in the area, but whenever I had a chance to play arcade games, that always took priority, especially when there were none in my immediate area... until the day I found out there was! A local kid told me that Emma's had an arcade game, and not just any game, but Donkey Kong! I couldn't believe it. It couldn't be true. Could it? Well, there was only one way to know for sure. So my 12 y.o. self did what any 12 y.o. would do. I got a pocketful of quarters, and I headed to the ba-ar...

There it was. Except, it didn't look the same. For one thing, it was called Congorilla. Now, you can see by the photo the marquee says "Congorilla". Even the manual included with it says "Congorilla". But that's not what the title screen said - the machine I first saw in early 1982 said Crazy Kong Part II on the title screen! For another, the cabinet wasn't the familiar blue one, but rather this typical woodgrain one that I'd see some other arcade games in. The colors on the game screen were different, but otherwise the graphics looked the same. I dropped in a quarter and start playing. Whoa. Is the speaker bad? This doesn't sound the same at all! And why is it every time my character jumps, it sounds like I'm kicking a chicken or something? I'm not a good Donkey Kong player at this time in my life, and an even worse Congorilla player. That doesn't matter, though. I'm playing a video game - an arcade video game - and there's nothing I'd rather be doing right now. I quickly exhausted the few quarters I had on me, and left the bar, which is empty except for the bartender. It's like a Saturday afternoon in the spring, and the place only seemed busy at night on the weekends. I know that as soon as I can earn more allowance or money from doing chores, I'll be back. My next time at the bar would be quite different, though, for unbeknownst to me, I was about to get kicked out of it. As soon as I entered and got halfway to the machine, the bartender (maybe a different one.. I don't remember) made it quite clear I wasn't wanted there and had to leave immediately.

"Hey! You're not supposed to be in here... get out!"

I must have been 5 shades of confusion. I was just in there a week or so ago, and there wasn't a problem, but now there was? I don't belong here? Of course I do. There's an arcade game right there! Well, what my 12 y.o. self didn't know until much later was anyone under 18 can't be in a bar, and that's that. Doesn't matter if you simply want to play an arcade game - something designed for anyone to play but specifically targeted to my demographic. Doesn't matter if it's the middle of the day and the place is empty. Well, I wasn't about to challenge some surly bartender on my inalienable rights to play video games. Besides, being in the comfort of my home playing my Atari was better than being in some dingy bar, especially one that looked like it hadn't seen the business end of a mop in years, and smelled like fresh air got kicked out long before I did. Anyway, it wouldn't be long before I learned a home version of Donkey Kong was on the way soon, thanks to Coleco.

|

SEQUELS |

While all the various home versions were being developed, Nintendo was hard at work making a few arcade sequels to follow up on the runaway success with Donkey Kong.

Nintendo's Donkey Kong Junior.

Another 4 screens of action, plus 2 animated cut scenes instead

of the original's one.

Scene from King Kong with Kong in chains.

"Ladies and gentlemen! Boys and girls! Step right up and try your

luck with the free key you were given!"

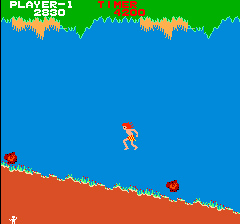

Donkey Kong Junior was again designed by Miyamoto and came out a year later in the U.S., in August of 1982, and flipped the script. This time around, the carpenter (now officially known as Mario) is the antagonist and you control Donkey Kong's protégé. Jumping is still an integral part of the gameplay, but instead of climbing ladders, you're now climbing vines, pipes, and chains. A few notable gameplay features were created. One involves dropping fruit on enemies. These take the place of the hammers from Donkey Kong and allow you to go on the offensive. All 4 screens feature fruit. Another screen involves a spring from the Donkey Kong elevators screen where if you jump on it and with proper timing jumping off it, you can land on either a lower or higher floating platform. Some of the platforms and vines on this particular screen aren't stationary but instead moved back-and-forth. The last new aspect is found on the last screen where you must push keys up to locks while climbing.

Ralston's Donkey Kong Junior cereal was an improvement in both taste and

texture.

Although the apple and banana pieces tasted like neither fruit, they

tasted better than the jagged 'wooden' barrels of the original.

Considering this is a direct follow-up to the events in Donkey Kong, are we to assume Donkey Kong consummated a relationship with the kidnapped lady? Did we cross some strange boundary here, moving beyond kidnapping to a subject involving bestiality? If so, seeing Kong in a cage no bigger than himself is a good first step. But that's a direction even Nintendo wouldn't take, so I suggest an alternate backstory where Kong and his mate had a real feces-flinging falling out, and Kong ends up at a construction site where the workers had stockpiled themselves with beer barrels from a local brewery. Kong goes on a ripper, grabs one of the worker's girlfriends, and the game is afoot. The flyer has this excerpt: "Watch how Junior strategically maneuvers his way to the top at high speeds. How he wrests the key away from Mario. The key that gives Papa the freedom to once again beat his chest and chase girls!" Is it really worth it for you to break your dad out of jail if he's going to continue to be a cheating louse? I mean, do you understand why he's in jail, junior? Miyamoto again goes to King Kong for "inspiration" for the final screen.

Nintendo's Sky Skipper. Miyamoto

certainly had a thing for gorillas...

Another Nintendo game, Sky Skipper, was developed right after Donkey Kong and was released a month later, in August 1981. Gorillas are again the villain. The game uses the same hardware as Popeye. Donkey Kong uses a 3 MHz Z-80 CPU and discrete logic for sounds, whereas both Sky Skipper and Popeye uses a 4 MHz Z-80 CPU and a 2 MHz AY8910 sound chip.

Nintendo's Popeye. Ironic how

quickly King Features Syndicate changed their tune about licensing their Popeye

characters...

Donkey Kong's success meant Miyamoto and Nintendo would get a Popeye-based game, and they did a year later, when Nintendo released Popeye in December 1982. I wonder who called who first, Nintendo or King Features Syndicate? The game only has 3 screens. Conversions were made for several consoles and computers at the time (Atari VCS, Atari 400/800/5200, Colecovision, Commodore 64, Intellivision, Odyssey2, and Texas Instruments TI-99/4a). Parker Brothers got both the home console and computer licensing.

Nintendo's Donkey Kong 3. Stanley

getting crazy ape bonkers with pesticides. So, Kong is up there batting

beehives, but I'm the one who gets stung?

Scene from North by Northwest with Cary

Grant getting the mother of all crop dustings.

If Nintendo wanted to make a game

involving pesticides, they could do no worse than rip... I mean, take

inspiration from this movie.

Just as Donkey Kong was born from the ashes of Nintendo's

failed shooter, Radar Scope, things came full circle with Donkey Kong 3 the following year, in

October of 1983. Again designed by Miyamoto, it combines the popularity of the Donkey Kong character, the

excitement of Namco's Galaga, and the adventurous setting of... a greenhouse

full of bees? Mario is out. Junior is out. Hell, even Luigi is

out. Enter... Stanley?

Donkey Kong 3 is certainly an odd little shooter that has a lot more in common

with games like Stratovox than it does with Donkey Kong. One look at

Stanley would make the case for inbreeding being the subversive topic this time

around. Or maybe Stanley has been huffin too many pesticides. In

spite of it being unpopular, there was a version for the Nintendo NES and even a

Game & Watch version, as well as an extremely rare sequel for the Sharp X1

called Donkey Kong 3: The Great Counterattack that was discovered in 2018

(LINK),

but other than the completists out there, nobody's really looking to have this

one in their collection. Seems Nintendo exhausted the King Kong

wellspring at this point, but luckily there were decades ahead with games involving the main

characters, and plenty of new (and better!) characters as well.

the following year, in

October of 1983. Again designed by Miyamoto, it combines the popularity of the Donkey Kong character, the

excitement of Namco's Galaga, and the adventurous setting of... a greenhouse

full of bees? Mario is out. Junior is out. Hell, even Luigi is

out. Enter... Stanley?

Donkey Kong 3 is certainly an odd little shooter that has a lot more in common

with games like Stratovox than it does with Donkey Kong. One look at

Stanley would make the case for inbreeding being the subversive topic this time

around. Or maybe Stanley has been huffin too many pesticides. In

spite of it being unpopular, there was a version for the Nintendo NES and even a

Game & Watch version, as well as an extremely rare sequel for the Sharp X1

called Donkey Kong 3: The Great Counterattack that was discovered in 2018

(LINK),

but other than the completists out there, nobody's really looking to have this

one in their collection. Seems Nintendo exhausted the King Kong

wellspring at this point, but luckily there were decades ahead with games involving the main

characters, and plenty of new (and better!) characters as well.

![]()

|

PIRATE VERSIONS |

Rather than try and cover every official Donkey Kong and Mario game ever made for every system (which would make one dandy college thesis), I'll continue covering all the Donkey Kong clones and pirate versions, up to and including the official NES version.

Congorilla machines were very common in my area (Northeast PA), and all the ones I've personally see had Falcon's Crazy Kong Part II boards. In the early 2000s, one of the local arcade operators I worked for had 2 similar Congorilla machines, and both had Falcon boards in them; considering the operator was the closest to Emma's, there's a good chance one of those machines was the very same one I played back then! The cabinets also had the infamous license sticker on the back of the cabinets, which of course "wasn't worth a plugged nickel" in the U.S. The KLOV entry for Congorilla mentions these were produced by Orca. I'm not sure how accurate that info is, as I'm reasonably sure Orca only produced games and boardsets, but I know there's several bootleg variations of Falcon's Crazy Kong ROMset, one of which was made by Orca (the title screen simply says "Crazy Kong 1981"). Another similarly titled version was made by Alca. And although there's a Congorilla manual, there was never a Congorilla ROMset or boardset as far as I know. The Congorilla name (as well as the cabinet artwork) was something one of the pirate companies I mentioned came up with.

Falcon's

Crazy Kong Part II shows an extra "GIVE UP!" message and

attract mode animation screens showing Kong busting out of a cage.

Alca's version of

Crazy Kong. Both Kong and

the carpenter are white as a ghost. I wonder if Nintendo's lawyers spooked

them.

Other than the title screens, Monkey Donkey and Donkey King

look and play exactly the same as Alca's version.

Also, Monkey Donkey doesn't

have a monkey instead of an ape/gorilla because monkeys have tails.

Orca's version

of Crazy Kong.

Big Kong starts with the cement factory screen, and then you get unique

ramps and elevators screens. The rivets screen has the carpenter getting a

little nosey with the lady.

Other bootleg variations of Falcon's Crazy Kong have been found under the names Big Kong and Monkey Donkey. Most of the variants have different colors and unique glitches (ex. you can walk behind Kong on the rivets screen). Big Kong has a unique glitch/trick where you can jump off the 2nd ramp and warp to the elevators screen! All of the Falcon boards and bootleg boards use the same hardware as Crazy Climber (fans of that game will recognize some of the sounds effects. Perhaps that's where Falcon got the idea to call it Crazy Kong?) They also have Kong graphics with "holes" in it where you can see the building graphics behind him. There's also Crazy Kong bootleg variants that use either Galaxian or Scramble hardware. If you thought Donkey Kong sounded bad with Crazy Climber sound effects, just wait until you try it with Galaxian's (will my ears never stop bleeding....?) What's really interesting with all of these bootlegs is, they all seem to share either the same Falcon Crazy Kong code, or a variation of it. I've yet to see one bootleg that uses the original Donkey Kong code, and if none do, this all goes back to Nintendo's deal with Falcon. For example, all the cut screens showing how high you've climbed say "How High Can You Get?" This is what the original Japanese version of Donkey Kong says; the U.S. version asks the more grammatically correct question "How High Can You Climb?"

As to what or who caused this mass influx of Donkey Kong arcade versions, the answer is Nintendo Co., Ltd. (unintentionally) created this problem. Sure, Donkey Kong would have been bootlegged otherwise, but damn, Nintendo bootlegged themselves before anyone else had the chance to. Nintendo was struggling to meet the demand for Donkey Kong machines and they decided to grant a license to Falcon Industries of Japan in September 1981 to create and sell a variant of Donkey Kong called (you guessed it) Crazy Kong. The agreement stipulated Falcon could only sell copies in Japan, as only Nintendo of America (a subsidy of Nintendo Co.) had the rights to sell Donkey Kong in the U.S. Nintendo Co., Ltd. supplied stickers to Falcon to attach to their Crazy Kong pcbs. The stickers were printed in the English language and indicated that the Crazy Kong circuit board was manufactured under a license from Nintendo Co. Falcon's version was based on the latest version of the Japanese ROMset (set #3), as evident of a ladder trick found in that version (LINK). It wasn't long before Falcon violated their agreement with Nintendo and exported Crazy Kong boards to the U.S., where they ended up on the hands of companies like Direct Connection and Arctic International (who were based in New Jersey and had previously been in legal trouble with Williams Electronics LINK). Falcon made no mention of the boards being illegal outside of the U.S., and being the license stickers were in English, anyone buying them assumed they were legal. One such Falcon board purchaser was Elcon (Electronic Concept Industries), who purchased their boards from Arctic in November 1981. Elcon was founded in Michigan in the 1970s by Andre Dubel and incorporated on September 2nd, 1977. Before long, the illegal boards were everywhere. Most arcade operators looking to buy a Donkey Kong machine either couldn't afford the retail price for them, or they were unavailable due to the high demand for them, soon found out about the bootleg machines, and the machine of choice in my area was Congorilla.

Needless to say, Nintendo soon found out what Falcon was doing and terminated the licensing agreement with them, on January 29th, 1982 to be specific. Nintendo of America sued Elcon and several other businesses (the only case with information online is the one against Elcon):

Nintendo of America, Inc. v. Falcon

Industries, Inc., Civ. No. 81-6359 (Feb. 12, 1982)

Nintendo of America, Inc. v. Artic International, Civ. No. (April 8, 1982)

Nintendo of America, Inc. v. Entertainment Industries, Civ. No. 82-631 (April 8,

1982)

Nintendo of America, Inc. v. Ingerman, Civ. No. 82-0937-C (June 26, 1982)

Nintendo of America, Inc. v. Elcon Industries, Inc., Civ. No. 82-72398 (October 4, 1982) (LINK)

Elcon argued that Ikegami Tsushinki Co., Ltd. - best known for creating high-quality television cameras (LINK) - created the game because they found that name in the program (LINK), but Nintendo showed evidence to the contrary and that Ikegami Tsushinki Co. only provided technical help with the programming. The following excerpt is from the Nintendo of America v. Elcon Industries case files:

|

Nintendo Co., Ltd. expended over $100,000.00 in direct development of the game, and Nintendo Co., Ltd. hired Ikegami Tsushinki Co., Ltd. to provide mechanical programming assistance to fix the software created by Nintendo Co., Ltd. in the storage component of the game. The name "Ikegami Co. Lim." appears in the computer program for the Donkey Kong game. Individuals within the research and development department of Nintendo Co., Ltd., however, created the Donkey Kong concept and game. The operation of the Donkey Kong game includes the use of the audio-visual material which was originally created for use in the game by Nintendo Co., Ltd. On July 27, 1981, Nintendo Co., Ltd. assigned all of its rights, title and interest in and to the United States copyrights in the Donkey Kong game to the plaintiff. The United States Copyright Registration No. PA 115-040 identifies Nintendo Co., Ltd. as the author of the entire audio-visual work[1] and indicates that plaintiff obtained ownership of the copyright through the assignment from Nintendo Co., Ltd. The copyright registration was issued to plaintiff with an effective date of July 30, 1982. It covers the entire audio-video presentation of the Donkey Kong game. Plaintiff has complied with all statutory requirements to perfect its copyright claim, including the display of a copyright notice on each game unit it distributes. [1] The Canadian application for registration of copyright for the Donkey Kong game filed by plaintiff states that Mr. Gunpei Yokoi is the author of the game. The evidence shows that Mr. Yokoi is one of the employees of Nintendo Co., Ltd. who did the creative work on the game. |

Nintendo's famous wanted ad that appeared in the

April 15th, 1982 issue of PlayMeter. It also appeared in RePlay.

News blurb from the August/September issue of

Video

Games Player (pg. 9).

Although Shigeru Miyamoto is often regarded as one of the most successful video game designers, he owes a huge debt of thanks to Yokoi not only for helping him create groundbreaking titles like Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. but with how to design games (LINK). As for Ikegami Tsushini's role in creating Donkey Kong, some believe Ikegami was contracted to develop the entire game based on concepts designed by Nintendo (from Miyamoto), but the Nintendo vs. Elcon court case downplayed Ikegami's involvement to more along the lines of code refinement and bug fixing. Yet all other evidence seems to point in the direction of Ikegami developing Donkey Kong entirely (as well as other early Nintendo arcade games). Why would Nintendo pay Ikegami some $90,000 (out of a budget of $267,000) to help fix a program, and why would Ikegami's logo be in Donkey Kong's graphics code? This site and Masumi Akagi's 2005 book It Started With Pong claims not only did Ikegami program Donkey Kong, they later sued Nintendo in 1983 (in the Tokyo District Court) for $580 million for using their code to develop Donkey Kong Junior without crediting or paying Ikegami, but it was not until 1989 that the Tokyo High Court gave a verdict that acknowledged the originality of program code. In 1990, Ikegami and Nintendo reached a settlement, but the terms of which were never disclosed. Allegedly there wasn't anything more than a verbal contract between the two, which makes Ikegami Tsushinki's involvement in Donkey Kong difficult to pinpoint, but this account goes in-depth as to how much work Ikegami spent on making Miyamoto's ideas into a functional and very playable game. If accurate, Ikegami's role with Donkey Kong was far more significant than Nintendo led everyone to believe, and any settlement on Nintendo's part would be an early example of them silencing a rival. Even Atari's lawsuit filings in its prime pale in comparison to Nintendo's litigious actions in the past 4 decades.

Junior King was another Donkey Kong Junior pirate version. Other

than a lack of any company info and some color variations, it looks identical.

This is a quick aside to another excerpt from the Nintendo of America v. Elcon Industries case files:

| Prior to July of 1981, Nintendo Co., Ltd. created and began manufacturing an audio-video game called Donkey Kong and first published the game in Japan on July 9, 1981. An English translation of the Japanese term Donkey Kong is "crazy gorilla." |

"Kong" is indeed a slang term for "gorilla" in Japanese. The name "Kong" is also associated with the Congo, an African country known for its gorillas. So if you were wondering where the name "Congorilla" came from, that would be it.

Falcon maintained they had no control over someone else buying their boards and exporting them to the U.S., but the judge wasn't buying it. Falcon even went on to bootleg Donkey Kong Junior, under the name Crazy Junior. This resulted in Falcon's CEO being arrested and sent to jail.

![]()

|

PLATFORM GENRE |

Donkey Kong's production numbers were hardly a secret, which is why Nintendo's competitors were looking a similar game of their own, as were companies looking to develop home versions. The following are games that took key elements from Donkey Kong and repurposed them, or showed them in a new angle. Some had storylines or a clear goal, and even some animation segues.

Amenip's Woodpecker (LEFT) and Naughty

(RIGHT).

Amenip released Naughty (called Naughty Mouse in MAME) AKA Woodpecker sometime in 1981. Though this game was unlikely influenced by Donkey Kong, it's interesting in that it's more similar to Space Panic. There's very little information about this game. A version of Woodpecker was released by a company called Palcom Queen River. In both versions, you control a mouse who has to convert all the egg nests into Casa De Rodentes. There's only one screen with each, but Woodpecker is more playable as you can go on the offensive by pressing the fire button; not so with Naughty, as you're only option is to run for your life, and it's nearly impossible to even clear the first screen. The game's premise was more fully realized with Mappy.

Atari's Kangaroo. The game

featured 4 different screens and as well as cut screens and whimsical animation.

Kangaroo is arguably the most popular copycat. Released in June 1982, the premise was to guide a mama kangaroo up 4 sections of a tree filled with platforms and ladders to rescue her baby kangaroo, whose been blindfolded and being held in a tree fort. Apparently, kangaroos are either born with boxing gloves or trained to be boxers at an early age, since baby k is shown wearing gloves. There's bonus fruit you can grab, if you can avoid the apple-throwing monkeys and the big ape with boxing gloves (he can steal your gloves, but you can steal them back). Now, why the monkeys would kidnap baby k is unknown. Perhaps their motivation was to cajole mama k into boxing their big boxing ape, or maybe they had already previously boxed each other and the ape lost, and this was the monkeys' way of avenging their betting losses. Tree boxing might not exactly be the UFC of the jungle, but much leather will be thrown.

This was made by Japanese company Sun Electronics. Atari, looking to cash in on the Donkey Kong craze like everyone else, decided Sun's game was close enough, licensed it, and fast-tracked it into production with only 1 week of playtesting. This of course did nothing to boost the morale of Atari's in-house game designers, who typically spent a year or more developing a game, and then often endured months of rigorous location testing by Atari's Marketing group to win their approval for release. Where management saw a very colorful looking and sounding Donkey Kongesque game on its surface, the coin-op designers were aghast to see a game with poor sprite hardware and gameplay that needed more fine-tuning, leading one of the engineers, Rich Adam, to write a particularly stinging memo about it:

|

There is an epidemic raging through the Coin-Op Marketing

and Engineering Management Staff. The disease is called License Fever.

It destroys the brain cells of its victims, crippling their thought processes.

These poor souls can no longer distinguish between a product that is junk and

one that has the quality the public identifies with Atari. How could a healthy, logical person make a decision to build a game of the caliber of Kangaroo based on one weeks collections report? Such a decision must be the result of a sever cranial dysfunction. The impact of Kangaroo to Coin-Op's reputation in the field is discouraging to think about. More serious, however, is the impact within Engineering. The project teams that develop games here work extremely hard. For these individuals to have to compete with trash games like Kangaroo and Fly Boy for Engineering support creates a very real morale problem. The mere consideration of these half-done games as a marketable product is confusing to Engineers who are used to much higher standards. Result: Even lower morale. The most recent example of this problem is the decision to remove Lunar Battle from field test so that Fly Boy and Maze Invaders could be tested at that location. Lunar Battle was tested long enough to get only two full weeks of collection reports. Based on this huge data base, the earnings curve looks like this (straight down). The project team on Lunar Battle was deprived of crucial information about game times, the game times curve looks like this (straight up). Information was lost on average scores, average scores curve looks like this (straight up). Information was lost on the ability of the player to max out the difficulty of the game. But nobody did it, in the three weeks that it was tested. As a member of the Lunar Battle project team I feel cheated out of that essential data. The point here is this: In light of all the priority which is being given to these inferior games I must ask myself, "Why am I working so hard to make a quality product?" |

Kangaroo sold in higher numbers than other Atari hits at the time, such as Crystal Castles and Millipede, and in slightly less numbers than Dig Dug and Star Wars. Kaneko's Fly-Boy actually saw production under the name Fast Freddie, but in extremely limited numbers, whereas Atari's equally poor Maze Invaders was never released. But if you ask arcade collectors and players these days, they'd likely choose to have any of those other games if given a choice, and if Donkey Kong is an option, there's no contest as to which they'd prefer. As for Lunar Battle (the early name for Gravitar), its production was cut short due to poor sales (about half of Kangaroo's numbers) and the remaining empty Gravitar cabinets were repurposed for Black Widow (with stickers of new artwork on the sides of them). Cute games were in, and shooters like Major Havoc (another Atari game with an incredibly long development, which actually shipped unfinished) were out. Actually, the tide had begun to turn with Pac-Man, and cute games were never Atari's forte. A review in the 1st issue of Creative Computing called it relatively non-violent, which is hilarious considering the idea for the game can trace its roots to what's animal abuse/manipulation from the late 1800s (LINK 1 and LINK 2), and your character is wearing boxing gloves, and the only way to advance in the game is to punch the crap out of something or someone. Regardless, the game was popular in both the arcade and at home, and Atari made a small fortune picking up Donkey Kong's banana peelings. There was even a Kangaroo Saturday morning cartoon show. I must have missed the Gravitar one...

Besides an Atari 5200 version, there was also a version for the Atari 400/800, but it wasn't done by GCC... exactly. Atari programmer James Leiterman converted it for the 8-bit computers, and it was eventually released via APX. The only minor graphics difference between them is the 5200 version has red strawberries whereas in the computer version they’re more purplish. From James Leiterman:

| General Computer was contracted to only do a 5200 version. While at Atari, I had written a reverse disassembler that converted binary files back into source code with some documentation. I went through and corrected the mistakes of the tool to build the 800 version and sent it over to APX. They published it with no credit back to me as I requested. So, essentially, it was an internal hack! Mine had red strawberries while theirs had a purplish red or some non-red color. |

Taito's Jungle King.

Taito's Jungle King was released in August 1982 and featured 4 different scrolling scenarios with Tarzan swinging from vines, swimming with alligators, running up a hill while jumping over boulders, and jumping over natives to rescue a woman held hostage. Conversions were made for several consoles and computers at the time (Apple II, Atari VCS, Atari 400/800/5200, Colecovision, Commodore 64, Commodore VIC-20, IBM PC, and Texas Instruments TI-99/4a).

Nihon Bussan/AV Japan's BurgerTime.

Nihon Bussan/AV Japan's BurgerTime was released in November 1982 and licensed by Bally/Midway for the U.S. market. The game was originally titled Hamburger in Japan, but was renamed before being exported internationally. It featured 6 different screens where the player must make burgers by walking over different ingredients, which fall down to plates at the bottom of the screen. Hot dogs, eggs, and pickles will chase you around. You can't jump over them but you can temporarily stun them by throwing pepper at them. Conversions were made for several consoles and computers at the time (Apple II, Aquarius, Atari VCS, Atari 400/800/5200, Colecovision, Commodore 64, IBM PC, Intellivision, and Texas Instruments TI-99/4a).

Century Electronics' Logger.

Still photos belie the absolutely wooden gameplay experience being offered here.

Century Electronics (not to be confused with Centuri Electronics) showed this blatant rip-off at the November 1982 AMOA show called Logger. It's unknown if Nintendo went after them, but I can't imagine why they wouldn't have. I only saw one of these, and that was within the past few years, so I doubt very many were made.

Orca's Springer. You've seen one

level, you've seen them all.

Orca wasn't content with simply doing an illegal knockoff variation of Falcon's Crazy Kong. Released in December 1982, Springer was their attempt at doing a legit knockoff variation. Jump from cloud to cloud, kicking dragons and collecting objects in an effort to reach the sun. There's also dangerous objects such as cups falling from above, and what looks like a tube of toothpaste (or a hypodermic needle?) floating across the screen. The arcade version has an impressive number of different levels (over 30). Tigervision made home versions for the Atari VCS (3 levels), Atari 400/800 (10 levels), and Texas Instruments TI-99/4a. The gameplay with all of them is rather horrible.

Sigma Enterprises' Ponpoko.

If you can get to the last level, you deserve a beer...

Sigma Enterprises' Ponpoko was released in January 1983. It's a simple platformer with 20 different screens that has you collecting different fruit (except for level 20, in which beer is the item to collect!). All you can do is run and jump. You have no offensive capabilities, other than the option of doing a small or big jump. The game is more similar to Space Panic in that you don't have an end goal to achieve. After you reach the final level, the same level keeps repeating.

Universal Playland's Mouser.

Universal Playland (UPL) released Mouser in February 1983 that features 4 different screens having different platforms connected by ladders (with the 3rd screen having a lift connecting 2 platforms). This is another animal variant of Donkey Kong. The objective is to rescue your girlfriend cat who has been catnapped by mice that throw or roll things down at you, or appear to slide boxes at you and then disappear as soon as you get close to them. There's even an opening animation setting the stage. Spoiler alert - when you finally reach her after completing the 4th screen, the mice replace her with a pig. Those black plague-carrying swine!

Konami's Roc'n Rope.

Konami's Roc'n Rope was released in March 1983. There are 4 different screens, and the storyline is you're an archaeologist who needs to return the tail feathers of the "Roc" bird (also called the Bird of Fortune). You have to use your Rope Gun to climb up each ledge, avoiding the cavemen and dinosaurs (referred to as monsters on the flyer). You're only weapon is the Flash, which (very) temporarily blinds an enemy. There's also a pterodactyl flying by and dropping rocks (shouldn't that have been called the Roc bird?). Every time you reach the rockless Roc bird, it flies away with you hanging on to its tail feathers for dear life. When you reach it the 4th time (and every 4th time after that), you're shown a full-screen animation of the Roc bird flying. Good graphics aren't everything, and boy, does this game prove it. More time should have been spend fixing the flawed design. Conversions were made for the Atari VCS and Colecovision consoles.

Kaneko's Jump Coaster.

Kaneko's Jump Coaster was released in May 1983. It's a 3-screen platformer where you collect bags of money while avoiding monkeys and coasters, with the goal of either reaching your girlfriend (for 1,000 points) or going for the big bag o money for 10,000 points.

Sunsoft's Arabian.

Sunsoft's Arabian was released in June 1983 and was developed by Sun Electronics. You play a prince who must rescue his princess who's being kept in a castle. It features 4 screens where you're climbing ladders, poles, and vines, and running platforms (both stationary and moving) while jumping and slashing enemies. You have to collect 7 jugs to complete each screen. There's also an animated scene for rescuing her.

Sega's Hopper Robo.

Sega also released Hopper Robo in August 1983 that includes elements from Donkey Kong and Donkey Kong Junior. You play a robot who must collect boxes. There are different platforms you can jump up and climb onto, or you can jump on giant springs to bounce up to a platform. Hammers are occasionally thrown down at you.

Sanritsu's Dr. Micro.

Sanritsu's Dr. Micro was released in 1983. It's a 3-screen platformer that has you chasing after a mad scientist instead of the typical fair maiden.

Taito's Elevator Action.

Taito's Elevator Action was released in July of 1983. You start at the top of a 21-story building (apparently zip lining down from a higher building) and fight your way down to the street. If you love running around and jumping while firing a gun and grabbing documents, and have a passion for riding elevators and escalators, this is your game. No apes or gorillas this time around, only goons who all have the same tailor.

Atari's Crystal Castles.

Also released in July 1983 was Atari's Crystal Castles. It's a mix between Pac-Man and Donkey Kong. The buildings are three dimensional and you must collect all the gems in the maze. You also have a jump button. Some screens feature lifts that allow you to access other sections.

Centuri Electronic's Hunchback.

Century Electronics released Hunchback in September 1983 and it's essentially Activision's Pitfall! with a medieval makeover. The company was only around for about 4 years and this was their most popular title (in a lineup of forgettable titles). Check out this article about the company from All In For A Quarter's Keith Smith.

Sega's Congo Bongo.

Sega's 1983 Congo Bongo re-imagines Donkey Kong in a 3-D jungle landscape. A gorilla sets you on fire, inventing the Burning Man festival in the process. There are 4 different screens that you must traverse with the goal of setting a gorilla on fire, as payback (and if you're successful, better hope nobody tells PETA about it...). Sure, the graphics were mind-blowing back then, but the gameplay can often be unforgiving.

Atari's Peter Pack-Rat.

Atari's obscure Peter Pack-Rat was released in 1985. The game's objective is to navigate different layouts of platforms, ladders, and pipes to collect objects and return them to your nest. The graphics and sound effects were cutting edge at the time, but the playability was a step back.

![]()

|

ARCADE HACKS |

There have been several hacks and modifications done to the original Donkey Kong:

Jeff Kulczycki's

Donkey Kong II: Jumpman Returns.

The earliest was Donkey Kong II: Jumpman Returns (AKA D2K) in 2006 by Jeff Kulczycki. Besides having a new opening animation and extra 'intermission' animations between screens (one of which is similar to the hotfooting animation scene from Congo Bongo), it includes 4 new screens as well as variations of the originals.

John Kowalski's

Donkey Kong Remix.

John Kowalski revisited this 2007 Tandy Color Computer 3 Donkey Kong project in 2015, and released an arcade version of his efforts in 2016 called Donkey Kong Remix. Besides the 4 original screens, it includes the 5 modified screens, as well as 3 bonus screens.

John Kowalski's

Donkey Kong Remix.

John Kowalski also released a modified version of Donkey Kong Junior, called Donkey Kong Junior Remix, in 2017. Like his Donkey Kong Remix, it includes the 5 modified screens as 3 bonus screens, as well as the 4 original screens.

At least 14 other variations of Donkey Kong Remix have been made since:

Donkey Kong II

Donkey Kong II Pauline Returns

Donkey Kong Christmas Remix

Donkey Kong Pauline Edition

Donkey Kong Spooky Remix

Donkey Kong Deluxe Black Hammer Edition

Donkey Kong Deluxe Builders Edition

Donkey Kong Deluxe Drunken Master Edition

Donkey Kong Deluxe FHMC Edition

Donkey Kong Deluxe Miner 2049er Edition

Donkey Kong Deluxe Personal Edition

Donkey Kong Deluxe Rearranged Edition

Donkey Kong Deluxe Wild Barrel Edition

The Pauline variations call back an earlier hacking effort by video game designer Mike Mika. Back in 2013, he hacked a role-reversal version of NES Donkey Kong to allow the player to play as Pauline trying to rescue Mario, thanks to a suggestion by his daughter, who was familiar with a similar option in NES Super Mario Bros. 2 where one could play as Princess Toadstool (LINK).

Owners of the original arcade game can purchase Ultimate Donkey Kong 3DK Multigame - an add-on board for their machine (LINK) that include Donkey Kong Remix and the 14 other variations. John also sells his own multigame boards of different compilations through his own site.

Another prolific Donkey Kong hacker, Paul Goes, created no less than 20 different variations:

Paul Goes'

Donkey Kong Twisted Jungle.

Donkey Kong Accelerate

Donkey Kong Anniversary Edition

Donkey Kong Barrelboss

Donkey Kong Barrelpalooza

Donkey Kong Championship Edition

Donkey Kong Crazy Barrels Edition

Donkey Kong Duel

Donkey Kong Freerun Edition

Donkey Kong Hearthunt

Donkey Kong Into The Dark

Donkey Kong On The Run

Donkey Kong Pac-Man Crossover

Donkey Kong Randomized Edition

Donkey Kong Reverse

Donkey Kong RNDMZR

Donkey Kong Skip Start

Donkey Kong Springfinity

Donkey Kong Sprites & HitBoxes

Donkey Kong Twisted Jungle

Donkey Kong Wizardry

Most of these mainly offer different colors and graphics, with minimal changes to the platforms. He also hacked Crazy Kong Pt. II to have more accurate graphics and colors! Check out his site for more details.

Fred X. Quimby's hack of Donkey Kong to use

the graphics (Mario, girlfriend, barrels, and fireballs) and sound f/x from VCS Donkey Kong.

Lastly, on the subject of Donkey Kong arcade games, Fred Quimby created this version.

![]()

|

COLECO HOME VERSIONS |

Coleco's first Colecovision magazine ad.

Like every CES show, the 1982 Summer CES in Chicago, IL was full of surprises, with the biggest going to Coleco's announcement of their Colecovision system. It wasn't just an announcement, either, as Coleco was on the floor showing the Colecovision and several games! If that wasn't enough, the 'drop mic' moment was their system included what was then the greatest pack-in game, Donkey Kong, and it looked fantastic!

Coleco's Colecovision Donkey Kong.

Yes, it looked great at the time, especially considering no other home versions of the game yet existed. I'm rather surprised the video game magazines at the time weren't running cover stories about it. Although those screenshots raised the bar in terms of detailed graphics in home video games, the one glaring issue everyone noted was that the ramps screen had Donkey Kong on the wrong side. The rivets screen was also missing 1 level, leaving only 6 rivets to remove instead of 8. As is often the case, mere screenshots don't tell you the whole story. When I first played it (after already playing the VCS version), I recalled how slow it ran. Even the theme music played slower (but then again, that describes most of my experiences playing Colecovision games in that every time I play one, I feel my life leaving me). Going up and down ladders was like having teeth pulled (the undocumented trick of hesitating after you first climb before moving again made you move faster, which helped). That is, if you're lined up correctly with it (there's little margin for error). What certainly didn't help most players with that was the Colecovision's stubby joystick controllers. There were also some strange design choices that were made, as though more consideration was made as to how good it looked in screenshots. On the ramps screen, the oil barrel is already ablaze right at the start, but there's no animation to the flames. The fireballs on the ramp screen already start moving around before the intro music even stops playing, and they have a nasty habit of appearing right next to you if you're on the sides. On the elevators screen, there's no springs, but there is an extra foxfire on the top girder, which tends to hang out around the only ladder to access it. After several more times around, an extra foxfire is added to the elevators and rivets screens, with the extra foxfire on the elevators screen being added to the top girder. Throughout all of this, there's plenty of flickering graphics of both yourself and the enemy objects. Collision-detection is also rather poor, especially when using the hammer; on the ramps screen, you have to literally be right on top of fireballs to kill them. Finally, the instant you complete a screen, you immediately start the next screen. There were also only 3 of the 4 screens; as with most conversions, the conveyor belts screen wasn't included, nor are there any animations, or "How High Can You Get" screens. Most articles at the time simply chose to ignore these issues. One author in particular, Steven Kent of The First Quarter and The Ultimate History of Video Games went so far as to claim Coleco made a "flawless" version of Donkey Kong; it's hardly flawless, and Coleco was already planning on a Super Game Module for the system to allow for improved games.

Coleco paid $25 million for the home rights for the game that included both console and handheld versions. But wait! There's more! Coleco also announced plans to sell their games for both the Atari VCS and Mattel Intellivision, with Donkey Kong at the top of their list. Along with Donkey Kong, there was Carnival, Frenzy, Looping, Mouse Trap, Mr. Do!, Smurf: Rescue in Gargamel's Castle, Smurfette's Birthday, Turbo, Venture, Wild Western, and Zaxxon - all for the VCS. Coleco's early catalog featured a different list of games - Carnival, Cosmic Avenger, Donkey Kong, Lady Bug, Mouse Trap, Smurf, Turbo, Venture, and Zaxxon. According to at least 1 account, Coleco showed cartridges for all 9 games at the show. Whether or not there was anything inside the cartridges, or what games were actually shown, I don't know. It proposes an interesting question. If Coleco did demonstrate an early version of Smurf at that CES, it wouldn't be too much of a stretch to consider Activision's David Crane saw it and quickly set out making Pitfall.

Reading Atari's assessment of the June 1982 CES show of both themselves and of the competition, it's clear they recognized Coleco's entry into the video game market was strong and took them seriously. How could they not? Coleco's showing was nothing short of staggering, and with the console announced price of $200 when the VCS was still selling for approximately $135, especially considering Coleco planned to offer a VCS adapter for their system, there was no reason anyone would want to buy a VCS at that point. To one-up themselves, they also announced plans for owners to expand it into a full-fledged computer! And yet, if you read Atari's assessment, they were still focused on Mattel's Intellivision as their main competition... and they proved as much when they pushed out their 5200 system in November of that year, with 360-degree joysticks to rival the Intellivision's 'paltry' 16-direction joypad controllers. Atari's 2 main critiques about Coleco were equally clueless ("They want to be all things to all people" and "Never delivering on their promised advertising"). By the end of the year, you couldn't escape their advertising, and the result was Coleco sold 2 million consoles in less than 6 months. The Colecovision was available by the end of July in New York and Boston, and soon expanded to other large cities (Chicago, Los Angeles) before wide release nationwide in September and October. Not only did Atari lose out on nabbing the Donkey Kong license, they were about to lose the next generation console race, and badly. But, before all that happened, the first horse out of Coleco's stable was VCS Donkey Kong...

Atari's June 1982 CES review of Coleco's showing.

Article by Jim McCullaugh in the 6-19-82 issue of

Billboard (pg. 4)

Michael Blanchet's column from

the 6-23-82 edition of the Hartford Courant.

July and August announcements in The Video Game Update newsletter.

The story of how Coleco got the home console license for Donkey Kong over Atari highlights yet another colossal Atari fumble. Atari had the inside track on getting it, but Nintendo wanted to license it to someone who could make both video and electronic handheld games. Atari certainly had experience making handheld games, even though they had all but stopped all development of them by that point. Could they have offered that option to Nintendo? Of course. At the time (1981), Atari had Alan Alcorn heading up his R&D division where holographic Cosmos handheld was being developed, and Atari was on the verge of consolidating all their handheld development under a new division, Electronic Toys & Games. As we now know, Atari's CEO Ray Kassar only had eyes for the VCS, and the Cosmos was cancelled at the 11th hour to being released.

In the 4th part of the 2024 The Legend of SwordQuest podcast, "Descent Into Darkness", former Warner Bros. exec Manny Gerard recalled how Kassar let the opportunity to license Donkey Kong get away:

| Colecovision. I'll never forget. I was sitting at a meeting at Atari when the first Colecos hit the street. So, they went out and bought one, and they walked into the conference room, and they took it out of the box, and they opened it up, and they looked on it, and the engineer who looked at it said it's clearly a piece of shit. It was there. Having another competitor is not good, but what it had was Donkey Kong. And when I went in to (see) Kassar, who ran the company, I said, we knew how good Donkey Kong was. We had the most arrogant programmers in the world in the coin-op division, and they were telling us this was one of the great games of all time. Why did you let the game go? And he said to me, "Well, they (Nintendo) wanted $2 a cartridge per royalty. We weren't going to pay that." I said, Ray, what are you, stupid? The gross margins are 88% on the cartridges, and that was going to be one of the best games anybody ever saw. And forgetting that Coleco got it. |

This is exactly the sort of inaction you get when you hire the wrong person for the CEO job (it was Gerard who suggested Kassar fill the position after he fired Nolan Bushnell).

The deal Coleco struck with Nintendo for the home console rights to Donkey Kong included paying $200,000 up front, plus $1.40 per cartridge and $1 per handheld.

|

COLECO AND NINTENDO HANDHELDS |

(LEFT)

Coleco's Donkey Kong handheld game; (RIGHT)

screenshot.

(LEFT)

Coleco's Donkey Kong Junior prototype handheld game;

(RIGHT) Nintendo's Donkey Kong Jr. released handheld game.

Nintendo's Mario's Cement Factory handheld game.

This uses the same design as Nintendo's Donkey Kong Jr. handheld.

![]()

|

ATARI VCS/2600 |

(LEFT and CENTER) Coleco VCS Donkey Kong box;

(RIGHT) Coleco's Atari VCS catalog. Despite having a picture of the arcade

game

and the "PLAYS LIKE THE REAL ARCADE GAME" statement, you got a game that

played like it at its basics, but didn't look or sound quite like it.

Like how most people remember seeing VCS

Pac-Man for the first time, I remember the first time seeing VCS Donkey Kong.

A good friend of mine at the time, Joe Malarkey, begged his parents to

get him a copy. At the time, General Radio in Wilkes-Barre, PA was one of

*the* places for video games, as they often stocked nearly everything.

Toys 'R' Us were years away from opening a location in the area, so places to

buy games were usually limited to department and TV stores, with General Radio

being the latter. His mother had seen a newspaper ad for the game and

mentioned it to him, which was basically a starter's pistol to "Let the begging

begin!" I was over his house and witnessed this notable moment. His

father half-heard the discussion going on and inquired about this "Honkey Donk"

game, which had us roaring with laughter. Before long, plans were made to

drive down to General Radio the following morning to get the game. I

stayed over his house that night and went with him to the store the next

morning. So eager to get there, we arrived before the store even opened

(ads show they opened at 8:30am Monday - Saturday). I remember standing

out front and looking through the large glass windows. The game counter

was halfway back in the store along the left wall, far enough for us not to able

to see the treasure it contained, especially with the lights out. The

store was rather large and the floor space mostly consisted of TVs, VCRs,

stereos, appliances, movies, records, cassettes... it was basically Best Buy

before there was Best Buy. To 12 y.o. me, it was a huge store :)

Come 8:30, the store opened and we rushed over to the video game counter.

A few minutes later, we followed a salesman over to a floor TV model in the

middle of the store where a VCS was hooked up. He plugged the game in and

powered everything up for my friend to try the game first before his mother bought it.

up for my friend to try the game first before his mother bought it.

As the TV warmed up, we saw the ramps screen with the main characters slowly appear on the screen. A tinge of disappointment immediately washed over me. Though not as shocking as when first seeing Pac-Man, it was still a letdown from how detailed the arcade version was (and especially moreso after seeing the Colecovision's version a few months later). My first thought was the game area looked 'small'. The playfield had large, blank spaces on both sides, where previously every other game I'd seen would fill the entire screen. Garry Kitchen's reason for this was to approximate the original vertical orientation of the arcade game. The jumpman character (now known as simply the carpenter for his penchant for hammering, but soon to be given an Italian name more famous than Rocky Balboa) looked recognizable and the rolling barrels were okay (even if they more closely resembled pepperoni pizzas), but the girl-to-be-rescued never once moved or cried out for help, frozen in shock at what looked like a giant gingerbread man standing next to her. Hey, the hammer was there, so at least it has that! Anybody can jump... people, animals, robots, aliens... anybody. Not many games involve the use of hammers, and even less carpenters are useful without one.

The game starts and you get right to it. You don't see Donkey Kong climbing a ladder to the top of the building and seeing him jumping up and down creating the ramps, or any baring of gorilla teeth. There's no "How High Can You Get?" screen. But as my friend started playing, I noticed when the barrels reached the bottom and touched the large oil drum in the lower-left corner, the drum didn't explode and start tossing out fireballs. Nothing happened with it. Okay, maybe that's a difficulty switch thing, much like how the saucers in Asteroids were optional. He didn't get to the top of the screen, and I don't remember if he asked if there were more screens. The box only showed 1 screen, so maybe the salesman confirmed there were more, or if we looked at the manual and saw there were more. In any case, he got the game (a few months later I did as well), and within minutes of getting back to his house, we played the game and saw the rivets screen. The fireballs showed the same lack of animation as the girlfriend, plus they didn't climb the ladders, which meant the hammer on that screen was only good for killing one fireball. Yep, that was kind of lame, as was not having the satisfaction of seeing the building collapse when you knocked out all the rivets. The restriction of only having 3 lives meant you had to get really good at the game to get a good score. There were also none of the bonus prizes that are found on the arcade's rivets screen. In other words, it's a pretty stripped down, bare-bones version.

Actual VCS Donkey Kong game screenshots, compared to actual

gingerbread man screenshot. You have to admit, the resemblance is uncanny.

Photo of typical slack-jawed gamer circa Christmas

1982, perhaps playing Donkey Kong?

From a programmer's point-of-view, it's a real technological achievement with the technical limitations in which to develop it. From a gamer's point-of-view, it's a somewhat disappointing version of the arcade game, featuring only 2 of the 4 screens and only 3 lives. Plus, kids don't understand things like technical limitations, time-to-market concerns, or budgets. You save or beg for a copy of a game that has the same name as that fantastic game you saw at the arcade, and you expect that copy to look, sound, and play the same. But as with most every game back then, that was rarely the case.

Nonetheless, it was a far more playable and enjoyable game than what the 800lb video game market gorilla Atari had to offer with their Pac-Man. As with most VCS games at the time, the graphics weren't always the main draw, the gameplay was, and in this category, Donkey Kong was acceptable. The reviews at the time were all over the place and ran the whole gamut, with the biggest gripes concerning the poor graphics and with only having 2 screens. Had the Colecovision not debuted with Donkey Kong as its pack-in game a mere 2 months later, I suspect opinions would have been more positive, but when the neighbor just got a Corvette and you're still driving a hand-me-down sedan, it's hard not to be biased.

The programmer for VCS Donkey Kong was Garry Kitchen. The game was contracted out to Woodside Design Associates (Steve Kitchen's company), who then contracted his brother Garry's company, Imaginative Systems Software. Coleco provided him with a Donkey Kong machine to use for reference, and he also spent a lot of time on the game so that it looked and played as close to the arcade version as possible. He mentioned incorporating the slanted ramps on the barrel screen was a real challenge, and originally had just straight (horizontal) ramps once he realized how hard having slanted ramps would be to program. He reached out to Activision during development in the hopes of securing a full-time job with them. The VP of Product Development at Activision, Thomas Lopez, came out to meet with him, and Garry showed him his progress with Donkey Kong. When leaving, the rep mentioned that if he worked for Activision, those ramps would have been slanted... which was all the motivation Garry needed to figure out how to do it. The game had to be finished by a specific date w/o question and he spent the last 72 hours straight (no sleep, no breaks) sitting in a cubicle in Hartford, Connecticut with the owners of Coleco standing over his shoulder waiting for the finished game. In October 2020, Kitchen wrote an article about the game's development, titled "How I Spent My Summer of 1982: The Making of Donkey Kong for the Atari 2600". He claimed he started programming the game in May and spending 3 months on it. The problem I have with that is, that timeline doesn't add up to when the game was actually released; by all accounts, the game was on the market in late July / early August (link). We know from the rushed development of Atari's VCS E.T. it took a good 8-10 weeks from the time a program was finished to when it ended up in stores. Knowing this, it's more likely Kitchen finished programming the game in May.

Earliest newspaper ad for Coleco's VCS Donkey

Kong, from the San Francisco Examiner 7-23-82.

General Radio ads from the Citizens' Voice

newspaper, 8-12-82 (LEFT) and 9-30-82 (RIGHT).

General Radio's first advertisement for the Colecovision 9-2-82.

General Radio & Electronic Co. at 587 S. Main St.,

Wilkes-Barre, PA

Auto Zone now has a location where General Radio

used to be.

According to Garry, Coleco wanted the game on the market in time for Christmas, which is why he was only given 3 months in which to develop it, and also why he was only given 4K to use instead of 8K. To Garry's credit, he tried to convince Coleco to use an 8K ROM since they were available by that time, but they refused due to the added cost. When he made it clear it would be impossible to include the other 2 screens without the extra ROM, he was told they didn't care because they were going to sell as many of them as they could make! Garry pleaded the other 2 levels were needed for the integrity of the game, but was told it didn't matter (VIDEO). Both of these reasons given to Garry were rather weak. VCS Donkey Kong was released in July - plenty of time for the holiday shopping season, right? As for their concerns over the extra cost of using 8K, for one thing, Donkey Kong was the hottest video game in the world in 1981. For another, Coleco debuted the Colecovision at the 1982 Summer CES show, along with carts for both the Atari VCS and Intellivision, so the first 4 VCS games Coleco released were either already done or close to being done by then, and they were worried about the cost of an 8K ROM? Exactly how much did they invest in the entire Colecovision project? And they were worried about 1 VCS title? Pul-eeze. I think their 'vision' was a little near-sighted. Besides, Coleco knew just from seeing how Atari fumbled having the license to the previous hottest video game in the world and how many VCS Pac-Man carts they sold that any version of Donkey Kong was going to sell millions. Garry's comment about integrity issues applied to both Coleco and Atari in that both company's leadership cared more about profit than the quality of their products. One would assume spending millions to acquire licenses would be all the motivation they would need to make every effort to make the best game or system they could, but if the games in question are already proven smash hits in the arcades, the only thing that mattered to them was having those names on their games; if the game looked or played even remotely the same, that was good enough.

Billboard magazine debuted their Top 15 Video Game chart list with their September 11th, 1982 issue. At that moment, Donkey Kong was already on the market and debuted at #3 on the list. The following issue didn't feature the chart, but the issue after that did, and Donkey Kong was now #1. It remained #1 for at least 6 weeks, up to November 6th, 1982. The November 13th, 1982 issue again didn't feature the Top 15 list, but the following week had Donkey Kong at #2, supplanted by what became the sales juggernaut with Activision's Pitfall. Donkey Kong would remain on the Top 15 chart well into 1983.

Billboard Top 15 Video Games charts for

9-11-82, 9-25-82, and 11-20-82.

So how did VCS Donkey Kong sell? Over 4 million copies were sold, earning Coleco wholesale revenues in excess of $100 million dollars, even accounting for the brief VCS cartridge recall. Garry mentioned that of the more than 500 SKUs Coleco had on the market that year, VCS Donkey Kong accounted for 25% of Coleco's revenue! Coleco also sold 550,000 Colecovision systems by the end of the year (or in a staggering 4 months' time), and nearly as many in the 1st quarter of 1983. A news blurb in the September 1983 issue of Electronic Games mentions Coleco sold its 1 millionth Colecovision in March of that year:

|

COLECO COLECOVISION/ADAM |

News blurb from the September 1983 issue of

Electronic Games

(pg. 8).

You're probably asking yourself, "What recall?" The 2nd issue of Arcade Express mentions Coleco had to recall the initial shipments of cartridges due to a problem with the original VCS (6-switch) models. A statement in the January 1983 issue of Electronic Games (pg. 21) confirms it was a problem with the original shells.

Coleco Donkey Kong recall blurbs from

Arcade Express (LEFT) and

Electronic Games

(RIGHT).

I asked Garry if he could confirm/deny the recall issue:

| I was not aware of this at all. Must have been a physical issue with the housing, as the code was never modified or updated. |

Since Donkey Kong was Coleco's first VCS release (with their 2nd, Venture, not being released until September, along with Mouse Trap in October, and Carnival in November), the recall only affected Donkey Kong.

Coleco would go on to sell over 2 million Colecovision systems before a combination of the video game industry crash and Coleco's ill-fated decision to focus on their ADAM computer project ultimately cut the console's life short, with Coleco declaring bankruptcy in 1988.

At the Winter 1984 CES show, Coleco unveiled the 3rd expansion module for their Colecovision, called the Super Game Module. The planned pack-in game with it was to be Super Donkey Kong. This was an improved version of their original, now including all 4 screens as well as the opening and end animations. Several other titles were being worked on, including Super Buck Rogers, Super Donkey Kong Junior, Dragon's Lair, and Super Smurf Rescue.

(LEFT) Coleco press release letter about the Super

Game Module #3; (RIGHT) photo of Super Donkey Kong wafer tape.

Coleco magazine ad that mentions the Super Game

Module.

Coleco's ADAM Donkey Kong.